The Need for Mental Health Care Among Informal Caregivers

Why is this important to me?

Approximately 30% of people with MS require help at home due to disability. Around 80% of such care is provided by an informal, unpaid caregiver who is frequently a spouse or other family member. Helping one cope with MS can be physically and emotionally difficult and may have a negative effect on a caregiver's mental health. If a caregiver is struggling with poor mental health, he or she may not be able to provide the highest quality of care. Thus, understanding the association between providing care to someone with MS and the caregiver’s mental health is important.

Who will benefit from reading this study/article?

People with MS who receive assistance from a family member or friend as well as their caregivers will benefit from reading this article.

What is the objective of this study?

The authors interviewed caregivers of people with MS who had a somewhat higher-level of disability and who required care at home. Results showed:

- Older caregivers tended to have less of a need for mental health care. In general, major depression appears to occur less frequently among older individuals. The attitudes and knowledge about mental health that these individuals share may help to explain their relatively low perceived need for mental health care.

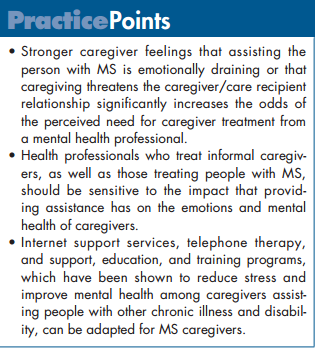

- A caregiver’s feeling that helping the person with MS is emotionally challenging was associated with an increased perception of a need for mental health counseling.

- A caregiver’s feeling that helping the person with MS strained the caregiver/patient relationship was associated with an increased perception of a need for mental health counseling.

- Better mental health of the caregiver was associated with a decreased perceived need for mental health counseling.

The findings of this study highlight the need for generating an awareness of the mental and emotional needs of caregivers of people with MS. It is important that you and your caregiver share concerns regarding the stress of care with your healthcare professional. Your healthcare provider can direct you to support services, telephone therapy, education, and training programs that can help to reduce stress.

How did the authors study this issue?

The authors contacted people with MS who are participants in the NARCOMS Registry, which includes 35,000 people with MS and represents about 10% of people with MS in the US. The authors focused on people with MS who had a somewhat high level of disability and who were therefore likely to require assistance at home. Phone interviews were conducted with MS patients and their caregivers. Of the 530 caregivers who participated, approximately half were male, and their average age was 59.5 years. 83% of caregivers were the spouse or partner of the person with MS. The investigators asked the caregivers a variety of questions about the person with MS, the care they provide, and their feelings about providing care. In particular, care providers were asked about the health and abilities of the person with MS, their feelings associated with providing care, their mental health status, and if they thought they would benefit from counseling from a mental healthcare provider.

| SHARE: | |||||

For additional resources, visit:

Original Article

The Need for Mental Health Care Among Informal Caregivers Assisting People with Multiple Sclerosis

International Journal of MS Care

Robert J. Buchanan, PhD; Chunfeng Huang, PhD

The objective of this study was to identify characteristics of informal caregivers and people with multiple sclerosis (MS) receiving assistance that are associated with the caregiver’s perceived need for mental health care. Survey data were collected in interviews with 530 caregivers and analyzed using a logistic regression model. We found that older caregiver age significantly decreased the odds of caregivers’ perceived need for mental health treatment. Better mental health domains of health-related quality of life among caregivers, as measured by the 8-item Short Form Health Status Survey (SF-8), also were associated with decreased odds of the need for mental health care. In contrast, the caregiver’s feeling that providing assistance was emotionally draining or the belief that this assistance threatened the caregiver/care recipient relationship significantly increased the odds of caregivers’ needing mental health treatment. Health professionals treating informal caregivers should be sensitive to the impact that providing assistance has on the emotions, relationships, and mental health needs of caregivers.

Multiple sclerosis (MS), a neurodegenerative disorder of the central nervous system, is characterized by episodes of neurologic symptoms that are often followed by fixed neurologic deficits, increasing disability, and physical decline over 30 to 40 years.1 The progress and severity of MS symptoms are unpredictable, however, varying widely among people with the disease.2,3 About 30% of people with MS require some form of assistance at home, with 80% of that support at home provided by informal or unpaid caregivers.4 These informal MS caregivers are typically family members, predominantly spouses.4,5 Support from caregivers enables people with MS to remain at home as their functional dependence becomes more permanent and their need for personal assistance increases.6 Informal caregivers provide a range of services to people with MS, including personal care, homemaking, mobility assistance, transportation, and recreation.5,7,8

Helping family members cope with the impact of chronic illness can negatively affect the mental health of informal caregivers.9 Providing assistance to people with chronic and disabling conditions can be emotionally and physically draining, leading to psychological illness in the caregiver.10 For example, rates of depression are as high as 50% among informal caregivers assisting people who had a stroke; moreover, these caregivers experience high rates of anxiety.11 Burden is strongly related to depressive symptoms among caregivers, with negative implications for mental health dimensions of quality of life.9 Caregivers with poorer mental health outcomes are more likely to provide lower-quality care and assistance to older adults.12

The chronic and disabling course of MS can have negative impacts not only on the person with the disease but also on the family, placing MS caregivers at high risk for psychological morbidity.13 Caregivers assisting people with MS can experience distress and strain, decreasing their quality of life.14 Caregiver burden is a multidimensional reaction to factors associated with providing daily assistance to the person with MS, including physical, psychological, emotional, and social stressors.15 The objective of this study was to identify characteristics of informal caregivers, caregiving, and people with MS receiving assistance that are associated with the caregiver’s perceived need for mental health care.

Methods

The sample of caregivers for this study was recruited using the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) Registry. The NARCOMS Registry contains the names and contact information for 35,000 people with MS at least 18 years of age who volunteered to participate in routine data collection and other research projects.16 Registry participants are assured confidentiality and that their names will not be disclosed to anyone without the participant’s written permission.

Sample Selection

A sample of 530 caregivers was developed by contacting people with MS participating in the NARCOMS Registry who were more functionally dependent, with dependence measured using the Patient-Determined Disease Steps (PDDS). The purpose of this caregiver survey was to learn more about the experiences, attitudes, and needs of MS caregivers assisting more functionally dependent people with MS. We focused on informal caregiving to people with MS who had greater disability and were more functionally dependent because they would be likely to require significant amounts of assistance with daily activities.

The PDDS, a self-assessment of mobility, is scored from 0 (normal) to 8 (bedridden).17 The PDDS was developed as a surrogate for the physician-administered Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS), which is recognized as the gold standard for measuring physical disability and neurologic impairment in people with MS.18 Scores from the PDDS are strongly linked with those from the EDSS.17,18 We contacted only people with MS who needed a cane to walk 25 feet (PDDS score of 5), required bilateral support (score of 6), primarily used a wheelchair or scooter (score of 7), or were bedridden (score of 8). While our survey sample included only people with MS reporting greater levels of physical dependency, about 41% of participants in the NARCOMS update survey conducted during 2006 reported similar dependency levels.4

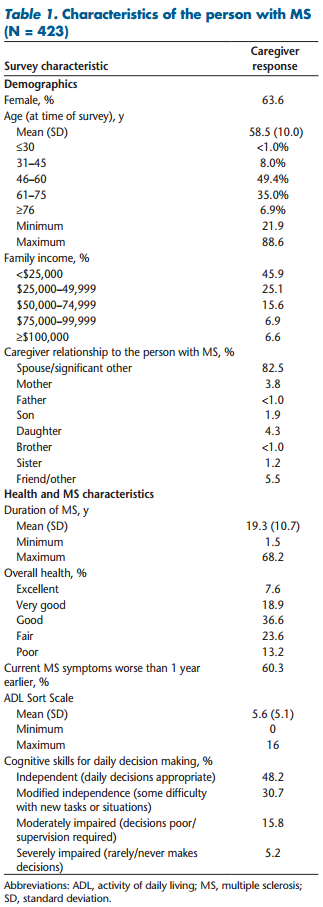

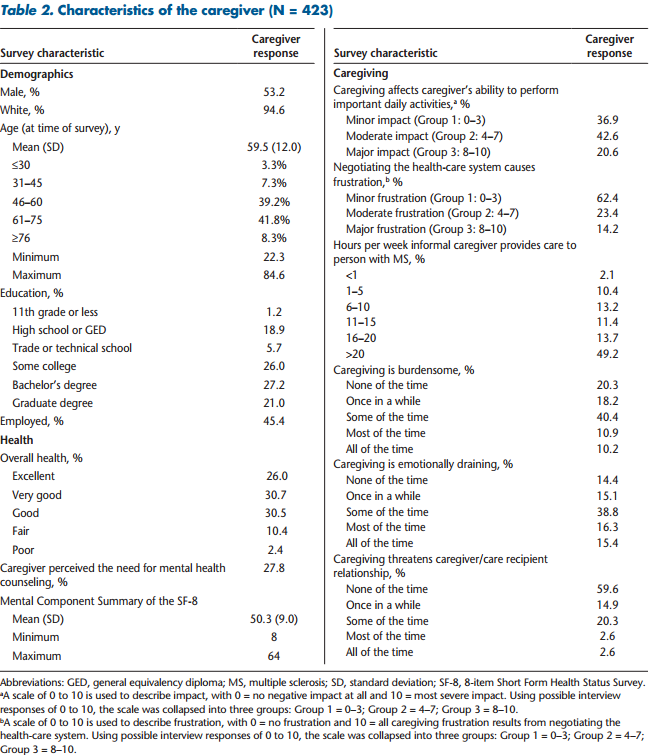

Characteristics of people with MS and their caregivers who are included in our caregiver/mental health analyses are presented in Tables 1 and 2. The people with MS in our study were predominantly female (63.6%) and averaged 58.5 years of age at the time of the survey, with almost half between the ages of 46 and 60 years. More than half of the caregivers (53.2%) were male, and caregivers averaged 59.5 years of age, with more than 40% between the ages of 61 and 75 years. About 83% of the caregivers were the spouse or “significant other” of the person with MS, while about 12% of the caregivers were other family members and about 6% were friends (or some “other” relationship) of the person with MS.

Although the data are not reported in Tables 1 and 2, about 42% of the informal caregivers in our caregiver/ mental health analyses reported that another unpaid caregiver helped the person with MS cope with the effects of the disease in the 12 months prior to the survey. Of caregivers reporting that other unpaid caregivers assisted the person with MS, 46.3% said a child of the person with MS provided unpaid care, 16.4% said friends or neighbors provided unpaid care, and 13.6% said a parent of the person with MS provided unpaid care. In addition, about 44% of the informal caregivers responded that a paid caregiver helped the person with MS cope with the impact of MS on daily life. However, about 93% of the informal caregivers participating in the survey reported that they provided most of the care and services to help the person with MS cope with the effects of the disease on daily life in the 12 months prior to the survey. About 4% of the survey respondents noted that paid caregivers provided most of the care and services to the person with MS, while only 2% of respondents said that other unpaid caregivers provided most of the care and services.

Survey Process

We identified 4943 NARCOMS Registry participants with MS who met the PDDS-based disability criteria to receive a recruitment letter, which requested their assistance to identify informal caregivers. This letter stated that we wanted to interview “the person who provides the majority of informal or unpaid care to you to help you cope with the effects of MS on your daily life.” This recruitment letter requested that the person with MS ask the caregiver who provided the majority of their informal care to call a toll-free telephone number to complete the interview. The computer-assisted telephone interview process was administered by the Public Policy Research Institute at Texas A&M University. The survey process was approved by the Office of Regulatory Compliance at Mississippi State University (study design and data analysis) in June 2006 and by the Office of Research Compliance, Institutional Review Board at Texas A&M University (interview process and survey administration), in July 2006.

Recruitment of survey participants began in September 2006, with about 1000 letters per week mailed, for a total mailing of 4071 letters. By December 2006, we completed interviews with 432 informal caregivers. Another batch of recruitment letters was mailed in January 2007 to 872 other people with MS who were not included in the September 2006 mailings. The survey process ended in March 2007, with interviews completed by a total of 530 informal caregivers assisting people with MS. The survey was stopped when no caregivers called to complete the telephone interview for 2 weeks.

Calculation of a participation rate is difficult because we do not know how many people with MS receiving the NARCOMS recruitment letter had an informal caregiver. The literature estimates that about 30% of people with MS require some form of home care, with 80% of that assistance at home provided by informal caregivers.4 Using those estimates, about 25% of people with MS have an informal caregiver, or about 1235 of the 4943 people with MS receiving our recruitment letters. Given the focus of this study on more functionally dependent people with MS, however, this estimate of 1235 informal caregivers may be low. Assuming 1235 informal caregivers, completion of 530 interviews yields a 43% participation rate.

Caregiver Interview Questionnaire

The survey recorded caregiver assessments of the impact MS had on the person receiving care, the care needs of the person with MS, MS disease and symptom characteristics, and how assisting the person with MS affected the caregiver. The interview took about 35 minutes to complete (median, 36.8 minutes). Focus groups—administered in Waltham, Massachusetts, during July 2004 and Springfield, Missouri, during August 2004—were conducted to help identify important issues and questions to include in the survey interview. The Ozark Branch of the Mid-America Chapter of the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (NMSS) recruited 8 informal caregivers assisting people with MS from the Springfield area and  the Greater New England Chapter of the NMSS recruited 12 informal MS caregivers from the Waltham area to participate in these focus groups.

the Greater New England Chapter of the NMSS recruited 12 informal MS caregivers from the Waltham area to participate in these focus groups.

Health Status and MS Symptoms

The interviewer asked the caregiver to assess the current overall health status of the person with MS, adapting a question from the 8-item Short Form Health Status Survey (SF-8).19 Survey questions on performance of activities of daily living (ADLs) and cognitive skills for daily decision making were taken from the “Minimum Data Set (MDS) for Nursing Home Resident Assessment and Care Screening.”20 These ADL responses were used to construct an ADL Short Scale to measure the functional dependence of the person with MS, based on the ADL Short Scale developed for analyses of data recorded in the MDS.21 The ADL Short Scale includes four ADL items: personal hygiene, toilet use, locomotion, and eating. Each ADL is scored on a scale of 0 to 4, with 0 indicating “independence” in the performance of the ADL and 4 indicating “total dependence.” The score for the ADL Short Scale for each person with MS can range from 0 to 16.

Caregiving

The interviewer asked caregivers to provide the average number of hours per week they spent “providing care and assistance to help [the person with MS] cope with the effects of MS.” The caregivers were asked to provide any number from 0 to 10 to describe how assisting the person with MS “affects your ability to perform activities in daily life that are important to you,” with 0 indicating no negative impact at all and 10 indicating the most severe impact. Caregivers were asked to describe how much of any caregiving burden or frustration that they may have experienced was caused by negotiating the health-care system using a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 indicating no frustration or burden and 10 indicating that all of their caregiving frustration or burden resulted from negotiating the health-care system. The interviewer read a list of statements assessing the feelings that caregivers may have experienced when assisting the person with MS, including “caregiving is burdensome,” “caregiving is emotionally draining,” and “caregiving has strained or threatened the caregiver/care recipient relationship.” These caregiver feelings were measured using a 5-point Likert item, with possible responses of none of the time, once in a while, some of the time, most of the time, and all of the time.

Health-Related Quality of Life

The interview included the SF-8, which is designed to provide a health-related quality of life (HRQOL) profile.19,22 In this study the SF-8 measured the HRQOL of the caregiver, not the person with MS. The SF-8 HRQOL profile consists of eight items and includes a Physical Component Summary and a Mental Component Summary, which are positively scored with higher scores indicating better health-related status. Previous studies documented the validity of the SF-8 in the United States,19 and the SF-8 meets standard evaluation criteria for content, construct, and criterion-related validity.22 We included the Mental Component Summary in our analysis as a measure of the mental health status of the caregiver.

Statistical Methods

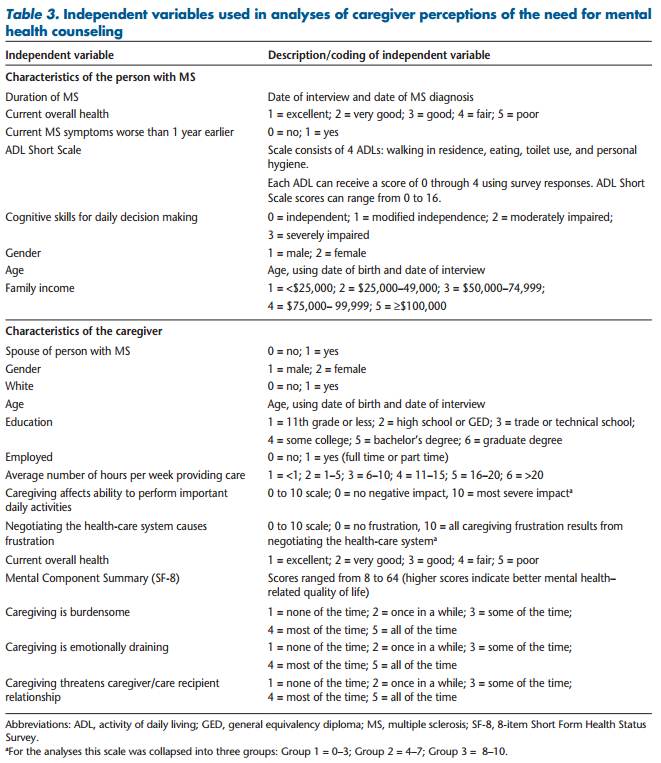

The independent variables in this study consisted of characteristics of the person with MS and characteristics of the caregiver, including the caregiver’s perceptions of caregiving. Table 3 presents these independent variables and describes how they were coded. Our analyses included 423 informal caregivers in the regression model (caregivers providing all data in their survey responses needed to implement our model).

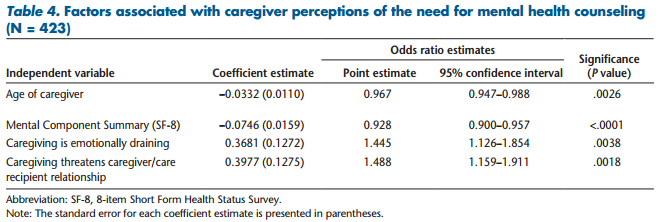

Interviewers asked the caregivers: “In the past 12 months did you think you needed or would benefit from treatment or counseling from a mental health professional such as a psychologist, psychiatrist, or mental health counselor or therapist?” This perceived caregiver need for mental health care is the dependent variable in our analyses. Because the study utilized a dichotomous dependent variable (coded as 0 = no; 1 = yes), we developed a logistic regression model. We utilized the stepwise selection procedure to reduce the number of independent variables in the initial  regression model. This procedure eliminates the least significant independent variables from the initial regression model, which included a range of independent variables that we theorized might be associated with the caregiver’s perceived need for mental health care. The stepwise selection method has the advantage of producing a small, readily interpretable model containing the most important predictor variables23 and is widely used in medically related applications.24 The initial regression model included 22 independent variables developed using survey response data. The stepwise selection procedure excluded 18 independent variables from this initial regression model, with the final model identifying 4 characteristics of caregivers and caregiving that were significantly associated with the caregiver’s perceived need for mental health care at the level of a = .05 (Table 4).

regression model. This procedure eliminates the least significant independent variables from the initial regression model, which included a range of independent variables that we theorized might be associated with the caregiver’s perceived need for mental health care. The stepwise selection method has the advantage of producing a small, readily interpretable model containing the most important predictor variables23 and is widely used in medically related applications.24 The initial regression model included 22 independent variables developed using survey response data. The stepwise selection procedure excluded 18 independent variables from this initial regression model, with the final model identifying 4 characteristics of caregivers and caregiving that were significantly associated with the caregiver’s perceived need for mental health care at the level of a = .05 (Table 4).

Results

The age of the caregiver was significantly linked to the caregiver’s perceived need for treatment from a mental health professional, with a 1-year increase in caregiver age decreasing the odds of this need for mental health care by 3.3%. A 10-year increase in age of the caregiver decreased the odds of the need for mental health counseling by 28.2%. Similarly, a one-point increase in the caregiver’s Mental Component Summary of the SF-8 decreased the odds of the need for mental health treatment by 7.2%.

In contrast, the caregiver’s feeling that assisting the person with MS was emotionally draining was significantly linked with increased odds of the perceived need for counseling from a mental health professional. A one unit increase in the caregiver’s feeling that caregiving was emotionally draining (eg, an increase from “some of the time” to “most of the time”) increased the odds of the caregiver’s need for mental health care by 44.5%. The caregiver’s belief that assisting the person with MS threatened the caregiver/care recipient relationship also was significantly associated with the caregiver’s need for mental health counseling. A one-unit increase in the belief that assisting the person with MS threatened the caregiver/ care recipient relationship (eg, an increase from “some of the time” to “most of the time”) increased the odds of the caregiver’s need for mental health care by 48.8%.

Discussion

We found that older age of caregivers significantly decreased the odds of the perceived need for treatment from a mental health professional. Lower prevalence of mental health conditions among the elderly could help explain our finding. Analyses of responses to the World Health Organization (WHO) World Mental Health (WMH) Survey found that rates of major depressive episodes varied significantly by age in developed countries, with the highest prevalence in the youngest adult age group and the lowest prevalence in the oldest age group.25 A study of Australians concluded that people aged 65 years and older were at lower risk for mental disorders than younger adults.26 A British study observed that the prevalence of psychological distress, mental illness, and related treatments rose with age until early middle age and then declined with older age.27 Analyses of WHO/WMH survey data found that utilization of treatments for emotional problems varied significantly with age in developed countries, with the oldest age group having the lowest use of these services.25

Age-related differences in attitudes and knowledge about mental health conditions and care also could explain our age-related findings of caregiver needs for mental health care. A study of Australians concluded that younger and middle-aged adults were more likely than older people to view counseling as the best form of help for depression.28 That study also found that younger adults were more likely than older adults to rate psychologists as helpful for treating depression. A US study involving a survey of more than 3300 people aged 65 years and older observed that health literacy was lower among older age groups.29

We found that emotional and mental health characteristics of the caregiver significantly affected the caregiver’s perceived need for treatment from a mental health professional. Better mental domains of HRQOL, as measured by the Mental Component Summary of the SF-8, significantly decreased the odds of the caregiver’s need for counseling. Stronger feelings that assisting the person with MS was emotionally draining or that caregiving threatened the caregiver/care recipient relationship significantly increased the odds of the need for treatment from a mental health professional. These findings highlight the importance of addressing the mental health and emotional care needs of informal caregivers assisting people with MS. Our findings are consistent with previous studies showing that assisting a person with MS can have a negative effect on the psychological well-being of the caregiver.14,30 Previous studies indicate that informal caregivers with poorer mental health outcomes are more likely to provide lower-quality care and assistance to older adults,12 while depression was a strong predictor of potentially harmful caregiver behavior among spouses assisting the impaired elderly.31 Because about 83% of the caregivers in our study had a spousal relationship to the person with MS, health professionals need to understand the stresses, burdens, worries, and experiences of spousal caregivers in order to provide appropriate mental health services and other support, such as respite care.32,33

Health professionals who treat informal caregivers, as well as health professionals treating people with MS, should be sensitive to the impact that providing assistance has on the emotions and mental health of informal caregivers. The American Medical Association (AMA) has developed an 18-item caregiver self-assessment questionnaire to help informal caregivers assess their own behavior and health risks.34 The physician treating the person with MS can provide this questionnaire to informal caregivers when they accompany the person receiving assistance to the physician’s office, or the caregiver’s own physician can ask the caregiver to complete the self-assessment questionnaire when the caregiver receives care. Physicians can discuss the results of the self-assessment questionnaire with informal caregivers and refer them to appropriate community resources if needed, such as support groups, respite care, social services, or further assessment to determine the need for counseling or other interventions.34

A study of family caregivers assisting visually impaired people, however, identified a number of obstacles that prevent physicians providing care to the visually impaired patient from screening the patient’s informal caregiver for mental health needs.35 These obstacles include time constraints, focus on the patient needing eye care, billing issues, and lack of familiarity with resources available to assist family caregivers. Physicians and other health-care providers treating people with MS would confront these same obstacles in efforts to screen informal caregivers assisting people with MS.

Patti et al.13 noted that health professionals need to be aware of support programs available to MS caregivers and refer caregivers to these programs. The various support services available to informal caregivers who assist people living with the effects of stroke provide examples of these programs. Telephone therapy and caregiver support, education, and training programs reduce stress and improve mental health among stroke caregivers.36 A Transition Assistance Program (TAP), developed to assist stroke caregivers, decreases caregiver strain and depression.37 TAP includes skill development, education, and supportive problem solving using videophone technology. Mental health professionals can adapt these stroke-related support programs to help MS caregivers. Future research is needed to identify intervention programs and support services that would be the most beneficial to informal caregivers assisting people with MS.

Earlier studies found that caregivers experienced high levels of stress and substantial burden, with the risk of “burnout” for those caregivers without support.38 Respite-care services provide informal caregivers with temporary relief from the stresses of providing assistance, allowing caregivers more opportunity to pursue important activities and decreasing burden.39 Respite-care services include adult day care, in-home respite, and institutional respite.38 MS-related Internet sites should include information on the benefits of respite care and how to access these services locally. For example, the Greater Carolinas Chapter of the NMSS maintains a website that describes a respite-care program available in the chapter’s service area.40

Study Limitations

This survey sample of informal caregivers was developed by contacting people with MS in the NARCOMS Registry. Participating in the NARCOMS Registry is voluntary, and members are not a random sample of people with MS, resulting in possible self-selection bias. However, the Registry membership is large, including about 10% of the American MS population.41 Registry participants have similar age at onset of MS symptoms and comparable demographic characteristics to people with MS in the National Health Interview Survey and the Slifka Study sample.41,42

Conclusion

Previous studies have found that informal caregivers with poorer mental health outcomes are more likely to provide lower-quality care and assistance, as well as exhibit potentially harmful caregiver behavior.12,31 Health professionals who treat MS caregivers, as well as health professionals treating people with MS, need to be sensitive to the impact that providing assistance has on the emotions, relationships, and mental health needs of caregivers. Health professionals can screen MS caregivers for behavior or health risks when they seek medical care using the AMA’s informal caregiver self-assessment questionnaire or when these caregivers accompany the person with MS to medical appointments.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Dr. Nicholas LaRocca, Vice President of the Health Care Delivery and Policy Research program of the NMSS, for his assistance with this research. The Lone Star Chapter of the NMSS recruited volunteers to pretest the caregiver survey questionnaire. The Central New England Chapter and the Ozark Branch of the Mid America Chapter of the NMSS recruited volunteers to participate in focus groups conducted for this study. In addition, the authors are grateful to the people with MS who identified their caregivers and the caregivers who participated in the focus groups, the pretest of the survey questionnaire, and the telephone interviews. Without their cooperation and input, this study could not have been completed.

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/Support: This research was supported by a contract from the Health Care Delivery and Policy Research Program of the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (HC 0043).

REFERENCES

1. Lublin F, Reingold S. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: results of an international survey. Neurology. 1996;46:907–911.

2. National Multiple Sclerosis Society. What we know about MS. http:// www.nationalmssociety.org/about-multiple-sclerosis/what-we-knowabout-ms/index.aspx. Accessed August 5, 2012.

3. Thompson AJ, Hobart JC. Multiple sclerosis: assessment of disability and disability scales. J Neurol. 1998;245:189–196.

4. Buchanan RJ, Radin D, Chakravorty B, et al. Informal care giving to more disabled people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31: 1244–1256.

5. Carton H, Loos R, Pacolet J, et al. A quantitative study of unpaid caregiving in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2000;6:274–279.

6. McKeown LP, Porter-Armstrong AP, Baxter GD. Caregivers of people with multiple sclerosis: experiences of support. Mult Scler. 2004;10:219–230.

7. Buchanan RJ, Radin D, Chakravorty B, et al. Perceptions of informal care givers: health and support services provided to people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32:500–510.

8. O’Hara L, DeSouza L, Ide L. The nature of care giving in a community sample of people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26: 1401–1410.

9. Chang HY, Chiou CJ, Chen NS. Impact of mental health and caregiver burden on family caregivers’ physical health. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;50:267–271.

10. Perrin PB, Heesacker M, Hinojosa MS, et al. Identifying at-risk, ethnically diverse stroke caregivers for counseling: a longitudinal study of mental health. Rehabil Psychol. 2009;54:138–149.

11. Perrin PB, Heesacker M, Stidham BS, et al. Structural equation modeling of the relationship between caregiver psychosocial variables and functioning of individuals with stroke. Rehabil Psychol. 2008;53:54–62.

12. Shaffer DR, Dooley WK, Williamson GM. Endorsement of proactively aggressive caregiving strategies moderates the relation between caregiver mental health and potentially harmful caregiving behavior. Psychol Aging. 2007;22:494–504.

13. Patti F, Amato MP, Battaglia MA, et al. Caregiver quality of life in multiple sclerosis: a multicentre Italian study. Mult Scler. 2007;13:412–419.

14. Khan F, Pallant J, Brand C. Caregiver strain and factors associated with caregiver self-efficacy and quality of life in a community cohort with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29:1241–1250.

15. Buhse M. Assessment of caregiver burden in families of persons with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2008;40:25–31.

16. North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) Project. Welcome to the NARCOMS Registry. http://narcoms.org/. Accessed August 5, 2012.

17. Marrie RA, Cutter G, Tyry T, et al. Does multiple sclerosis–associated disability differ between races? Neurology. 2006;66:1235–1240.

18. Orme M, Kerrigan J, Tyas D, et al. The effect of disease, functional status, and relapses on the utility of people with multiple sclerosis in the UK. Value Health. 2007;10:54–60.

19. Ware JE, Kosinkski M, Dewey JE, et al. How to Score and Interpret SingleItem Health Status Measures: A Manual for Users of the SF-8TM Health Survey. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Inc; 2001.

20. US Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Minimum Data Set (MDS)–Version 2.0–for Nursing Home Resident Assessment and Care Screening. Basic Assessment Tracking Form. http://www.cms.hhs.gov/NursingHomeQualityInits/Downloads/MDS20MDSAllForms.pdf. Accessed August 5, 2012.

21. Morris JN, Fries BE, Morris SA. Scaling ADLs within the MDS. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54:M546–M553.

22. Turner-Bowker DM, Bayliss MS, Ware JE, et al. Usefulness of the SF-8TM Health Survey for comparing the impact of migraine and other conditions. Qual Life Res. 2003;12:1003–1012.

23. Steyerberg E, Harrell FE. Statistical models for prognostication. In: Max MB, Lynn J, eds. Symptom Research: Methods and Opportunities. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health. Interactive textbook available online at: http://painconsortium.nih.gov/symptomresearch/. Accessed August 5, 2012.

24. Steyerberg EW, Eijkemans MJC, Harrell FE, et al. Prognostic modeling with logistic regression analysis: a comparison of selection and estimation methods in small data sets. Stat Med. 2000;19:1059–1079.

25. Kessler RC, Birnbaum HG, Shahly V, et al. Age differences in the prevalence and co-morbidity of DSM-IV major depressive episodes: results from the WHO World Mental Health Survey Initiative. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:351–364.

26. Trollor JN, Anderson TM, Sachdev PS, et al. Age shall not weary them: mental health in the middle-aged and the elderly. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2007;41:581–589.

27. Lang IA, Llewellyn DJ, Hubbard RE, et al. Income and the midlife peak in common mental disorder prevalence. Psychol Med. 2011;41: 1365–1372.

28. Farrer L, Leach L, Griffiths KM, et al. Age differences in mental health literacy. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:125. Available online at: http://www. biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/8/125. Accessed August 5, 2012.

29. Baker DW, Gazmararian JA, Sudano J, et al. The association between age and health literacy among elderly persons. J Gerontol: Soc Sci. 2000;55:S368–S374.

30. Knight RG, Devereux RC, Godfrey HP. Psychosocial consequences of caring for a spouse with multiple sclerosis. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1997;19:7–19.

31. Williamson GM, Shaffer DR, The Family Relationships in Late Life Project. Relationship quality and potentially harmful behaviors by spousal caregivers: how we were then, how we are now. Psychol Aging. 2001;16:217–226.

32. Cheung J, Hocking P. The experiences of spousal caregivers of people with multiple sclerosis. Qual Health Res. 2004;14:153–166.

33. Mutch K. In sickness and in health: experience of caring for a spouse with MS. Br J Nurs. 2010;19:214–219.

34. American Medical Association. Caregiver self-assessment. http://www. ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/public-health/promotinghealthy-lifestyles/geriatric-health/caregiver-health/caregiver-self-assessment.page#. Accessed August 5, 2012.

35. Bambara JK, Owsley C, Wadley V, et al. Family caregiver social problem-solving abilities and adjustment to caring for a relative with vision loss. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:1585–1592.

36. Grant JS, Elliott TR, Weaver M, et al. Telephone intervention with family caregivers of stroke survivors after rehabilitation. Stroke. 2002;33: 2060–2065.

37. Perrin PB, Johnston A, Vogel B, et al. A culturally sensitive Transition Assistance Program for stroke caregivers: examining caregiver mental health and stroke rehabilitation. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2010;47:605–616.

38. Mason A, Weatherly H, Spilsbury K, et al. The effectiveness and costeffectiveness of respite for caregivers of frail older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:290–297.

39. Whitlach CJ, Feinberg LF. Family and friends as respite providers. J Aging Soc Pol. 2006;18:127–139. 40. Greater Carolinas Chapter, National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Respite care. http://www.nationalmssociety.org/chapters/nct/programsservices/family-and-friends/respite-care/index.aspx. Accessed August 5, 2012.

41. Marrie RA, Horwitz R, Cutter G, et al. Comorbidity, socioeconomic status and multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2008;14:1091–1098.

42. Minden SL, Frankel D, Hadden L, et al. The Sonya Slifka Longitudinal Multiple Sclerosis Study: methods and sample characteristics. Mult Scler. 2006;12:24–38.