Associations Between Fatigue and Disability, Functional Mobility, Depression, and Quality of Life in People with Multiple Sclerosis

Why is this important to me?

Around 50-90% of people with MS will experience fatigue, which is one of the worst symptoms of the disease. Fatigue is defined as the lack of physical or mental energy that is needed to perform normal and desired daily activities. About one-quarter of people with MS report that fatigue makes other MS symptoms more apparent. Little is known about the relationship between fatigue and other symptoms of MS. This study examined the association between different levels of fatigue in people with MS and:

- Disability

- Mobility

- Depression

- Quality of life

Who will benefit from reading this study/article?

Because fatigue is so common in MS, all people with MS will benefit from reading this article.

What is the objective of this study?

Participants with MS were divided into two groups according to whether their level of fatigue was high or low. About 64% of the participants reported a high level of fatigue. The following associations were examined:

- Mobility and fatigue: Those with MS with higher levels of fatigue showed worse mobility.

- Depression and fatigue: Those with MS with higher levels of fatigue showed worse depression.

- Quality of life and fatigue: Those with MS with higher levels of fatigue showed lower quality of life.

- Disability and fatigue: In contrast to the above results, disability was similar regardless of the level of fatigue.

Fatigue may contribute to other symptoms of MS, quality of life, and participation in social and other activities. Understanding the association (or absence of an association) between fatigue and other symptoms of MS is important so that members of your medical team can suggest the therapeutic intervention that is most likely to provide you the best outcome. Early detection and treatment of fatigue are likely to improve your overall quality of life. Fatigue should be assessed by your medical team regardless of your disability level.

Limitations of this study are that it was not able to establish a cause-and-effect relationship between fatigue and other symptoms of MS and that other possible medical causes of fatigue were not investigated.

How did the authors study this issue?

The authors investigated 89 people with MS who visited an MS clinic in Utah and who completed several questionnaires and functional tests. Participants were not experiencing a relapse at the time of the study. Of these 89 participants, 66% were women. Fatigue, depression, and quality of life were determined with self-reported questionnaires. Mobility was determined with performance tests and self-reported questionnaires that assessed standing, walking, and balance. Disability was assessed with the Expanded Disability Status Scale and a neurological examination.

Original Article

Associations Between Fatigue and Disability, Functional Mobility, Depression, and Quality of Life in People with Multiple Sclerosis

International Journal of MS Care

Hina Garg, PT, MS, PhD; Steffani Bush, BS; Eduard Gappmaier, PhD, PT

Fatigue is a common yet poorly understood symptom in people with multiple sclerosis (MS) and is defined as a patient- or caregiver-perceived lack of physical or mental energy that may interfere with the performance of usual and desired daily activities.1 Fifty to ninety percent of people with MS report fatigue,2,3 and most rank fatigue as one of their worst symptoms.3 In addition, 28% of individuals state that fatigue makes other MS symptoms more apparent.4 Owing to the paucity of information on the pathogenesis of fatigue and its bearing on an individual with MS, it is important to investigate the associations between high levels of fatigue and other MS-related impairments, functional performance, and community participation.

Fatigue is a multifactorial phenomenon in MS5,6 and is attributed to primary or secondary disease mechanisms.7 Primary factors may include inflammation, demyelination, and destruction of axons in the central nervous system, the presence of immune markers, and neuroendocrine system disturbances. Secondary factors may include sleep problems, depression or other psychological variables, medications, and lack of exercise.7,8 The associations between fatigue and other MS-related other MS symptoms more apparent.4 Owing to the paucity of information on the pathogenesis of fatigue and its bearing on an individual with MS, it is important to investigate the associations between high levels of fatigue and other MS-related impairments, functional performance, and community participation. Fatigue is a multifactorial phenomenon in MS5,6 and is attributed to primary or secondary disease mechanisms.7 Primary factors may include inflammation, demyelination, and destruction of axons in the central nervous system, the presence of immune markers, and neuroendocrine system disturbances. Secondary factors may include sleep problems, depression or other psychological variables, medications, and lack of exercise.7,8 The associations between fatigue and other MS-related compared with people with MS who had low levels of fatigue.

Methods

Design

Data were collected from individuals with MS referred to a rehabilitation and wellness program at the University of Utah MS Rehabilitation and Wellness Clinic (Salt Lake City). As part of the program, each individual underwent a baseline medical evaluation of physical status and function to determine his or her specific exercise prescription. Evaluations were conducted by trained staff and included a comprehensive neuromuscular examination, functional mobility testing, and health status and fatigue questionnaires. Participants had signed a University of Utah institutional review board–approved consent form and agreed to utilization of their clinical data for cross-sectional research analyses. Baseline data from individuals referred to the program between 2007 and 2013 were included in this study.

Participants

The inclusion criteria were a clinically definite MS diagnosis, an Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score of 1 to 8 to encompass individuals with MS across a wider disability spectrum, and age older than 18 years. The exclusion criteria included a history or evidence of an acute exacerbation (<3 weeks). All the MS wellness program participants were referred by their neurologists, who screened and addressed other significant medical conditions before their participation in the program.

Procedures

Participant interviews provided information on demographic characteristics. Functional mobility tests and self-report assessments were performed with rest periods in between as required. The disability status measurements were conducted on a separate occasion to minimize fatigue. All testing was completed within 2 to 3 weeks.

Instruments and Measures

Fatigue.

Fatigue was determined by the MFIS-5, developed by the Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life Inventory panel to assess the impact of fatigue on the lives of individuals with MS. The short version was used for time efficiency; participants required less than 5 minutes to complete the self-report questionnaire. The items on the MFIS-5 inquired about the following: Because of fatigue during the past 4 weeks, have you been less alert? Have you been limited in your ability to do things away from home? Have you had trouble maintaining physical effort for long periods? Have you been less able to complete tasks that require physical effort? Have you had trouble concentrating? The MFIS-5 total score ranges from 0 to 20, with higher scores indicating greater fatigue. For this study, all the participants were divided into two groups: group LF included people with MS with MFIS-5 scores of 10 or less, indicating low levels of fatigue, and group HF included people with MS with MFIS-5 scores greater than 10, indicating high levels of fatigue. A cutoff score of greater than 10 was used to identify individuals with MS reporting a greater than “sometimes” impact of fatigue in performing daily activities on all the questions of the MFIS-5. Chwastiak et al.15 used this scale to categorize people with MS into groups of disabling and nondisabling fatigue. The longer version of the MFIS is a multidimensional scale to measure the perceived impact of fatigue on various activities of daily living and has been found to have good reliability and validity in MS.19,20

Functional Mobility Measures.

The functional mobility measures included the 8-foot Timed Up and Go (TUG) test, the Activities-specific Balance Confidence (ABC) scale, and the 12-item Multiple Sclerosis Walking Scale (MSWS-12). For the TUG test, participants were instructed to start from a seated position and rise to standing, walk forward 8 feet, turn around, and return to sitting as quickly as possible. Time was recorded to the nearest 0.01 second from the time of the word “go” until return contact with the buttocks on the chair.21 The fastest time of the two trials was used for analysis. Concurrent validity 22 and reliability 23 have been assessed in individuals with MS.

The ABC scale is a 16-item self-reported measure of balance confidence in performing various activities of daily living. Each question requires the individual to grade himself or herself on a scale from 0% to 100% for their level of confidence,24 and higher scores indicated greater balance confidence in performing these activities. The mean score for 16 items was analyzed in this study. The reliability and validity of the ABC scale have been studied in people with MS.22,25

The MSWS-12 is a 12-item measure of self-reported walking ability and balance in standing activities. Each item was scored on a scale from 1 to 5. Total MSWS-12 scores were generated by summing the scores from all items, subtracting the minimum score (12), dividing by the maximum score (48), and then multiplying by 100. High scores indicate a greater effect on walking ability. The test is reliable and correlates well with other self rating measures, such as the physical areas of the 29-item Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale, the 36-item Short Form Health Status Survey (physical functioning), the Functional Assessment of Multiple Sclerosis (mobility scale), and the Performance Scales.26 The reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.93) and precision (standard error of measurement = 8%, coefficient of variation = 27%) have been determined by Learmonth et al.27

Depression.

Depression was assessed by the modified Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-Fast Screen [BDI-FS]). This is a modified seven-item version of the traditional BDI. The BDI-FS is a self-reported survey with total responses ranging from 0 to 21, where higher scores indicated higher levels of depression. The BDI-FS has been previously validated in MS.28

Quality of life was measured using the Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 Instrument (MSQOL-54), a multidimensional self-report measure that includes both MS-specific and generic items. It generates 12 subscales, 2 summary scores, and 2 single-item measures.29 The two summary scores (physical QOL and mental QOL) were used for the study. Özakbas et al.30 compared the MSQOL-54 with two other QOL instruments and found it to be the most reliable measure of QOL in people with MS.

Neurologic disability was assessed by the EDSS. Disability status was measured as part of a standardized neurologic examination performed by an experienced licensed physical therapist using the Neurostatus assessment for determination of Kurtzke Functional System Scores and EDSS scores (Neurostatus Systems AG, Basel, Switzerland).31

Statistical Analysis

Nonparametric statistical methods were used because the assumptions of normality were not met. MannWhitney U tests for independent samples were conducted to determine the differences in dependent variables, which included neurologic disability status, functional mobility, depression, and physical and mental QOL. The independent variable was group membership; group LF included people with MS with MFIS-5 scores of 10 or less, indicating low levels of fatigue, and group HF included people with MS with MFIS-5 scores greater than 10, indicating high levels of fatigue. Effect size (ES) estimates were calculated by dividing the z score of test statistics by the square root of N, where N is the total number of observations. A statistical software program (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 20.0, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) was used, and the significance level was set at P ≤ .05.

Results

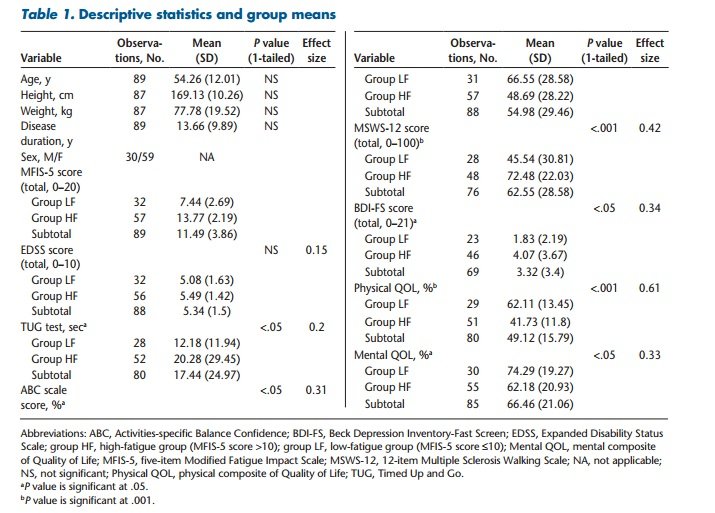

Of 89 participants, 59 (66%) were women. High levels of fatigue (MFIS-5 score >10) were reported by approximately 64% of the study sample (Table 1).

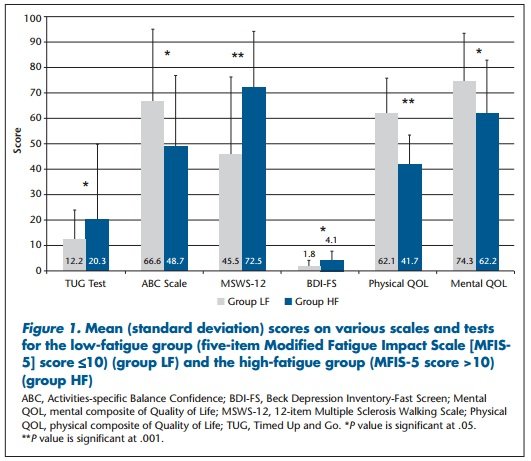

Compared with group LF, group HF demonstrated significantly (P < .05) greater impairments in TUG test (ES = 0.20), ABC scale (ES = 0.31), and MSWS-12 (ES = 0.42) scores, indicating that people with MS who report higher levels of fatigue also exhibit significantly higher impairments in objective and self-reported measures of functional mobility (Figure 1; Table 1).

Similarly, group HF demonstrated significantly (P < .05) higher BDI-FS scores (ES = 0.34) and decreased physical (ES = 0.61) and mental (ES = 0.33) QOL compared with group LF, indicating that people with MS who report greater levels of fatigue also exhibit greater signs of depression and diminished QOL (Figure 1; Table 1).

However, EDSS scores were not significantly different between groups (P > .05), demonstrating that both groups had similar disability status irrespective of the level of fatigue (Figure 1; Table 1).

Discussion

Fatigue is a common symptom in people with MS, but its associations with disability, functional mobility, depression, and QOL remain less studied. This study aimed to determine the associations between different levels of fatigue and neurologic disability, functional mobility, depression, and physical and mental QOL in people with MS. The results demonstrated that individuals with MS reporting a score greater than 10 on the MFIS-5 concomitantly demonstrated greater functional mobility impairments, increased depression, and decreased QOL as opposed to individuals with MS who report a score of 10 or less. Neurologic disability, however, was found to be similar across both groups.

The present study is the first to cross-sectionally examine the associations between different levels of fatigue and performance-based (TUG test) and self-reported (ABC scale and MSWS-12) measures of functional mobility in people with MS. Previous reports have determined that self-reported fatigue increases but that walking performance does not change from morning to afternoon in people with MS.32,33 A few studies have shown decreased performance of usual activities in people with MS who report high levels of fatigue.1,11,15,34 Although these studies effectively demonstrated a relationship between fatigue and daily activity in MS, the effect of differing fatigue levels on functional performance remained unclear. We determined that individuals with MS who scored greater than 10 on the MFIS-5 (group HF) took longer to perform the TUG test, reported decreased balance confidence in performing daily activities, and demonstrated a greater impact of MS on their walking ability. Significant mean differences with low-to-moderate ESs for the functional mobility measures were found between the groups (Table 1). This finding can be significant for a health-care provider to appropriately assess and manage a person with MS presenting with complaints of fatigue. Moreover, a time-efficient fatigue screening tool, such as the MFIS-5, can help the provider in early identification and suitable treatment of MS-related fatigue.

This study also demonstrated that people with MS who reported a score greater than 10 on the MFIS-5 (group HF) had higher scores on self-reported depression as measured by the BDI-FS. Depression has been identified as a contributor to secondary fatigue and vice versa.35 Bakshi et al.14 determined that MS-related fatigue is associated with depression even after controlling for physical disability, thereby suggesting that MS-related fatigue and depression share common mechanistic neural pathways. Although the design and analysis of the present study restricted us in controlling for neurologic disability, we found significant differences in depression scores across the groups along with no differences in neurologic disability, which is consistent with Bakshi et al.14 In contrast, Krupp et al.10 and Vercoulen et al.11 found no correlations between MS-related fatigue and depression. Both these studies had similar limitations in the study design, such as inclusion of individuals with lower disability scores on the EDSS, vague inclusion criteria, and the use of a less reliable and valid measure of fatigue, which might have been responsible for their findings. Recent studies, however, have used more sensitive measures of fatigue and have demonstrated a strong relationship between fatigue and depression in MS.14,15 The present study included a wider disability range and an abbreviated version of a sensitive fatigue measure (MFIS) previously used in MS, thus improving the relevance of these results to people with MS. The present findings confirm that an association between fatigue and depression is seen in MS; however, the causality and the direction of causality cannot be determined from these results.

The results of this study were found to be consistent with those of previous studies in determining a strong association between fatigue severity and the impact on QOL in people with MS. However, a greater ES was noted for physical QOL as opposed to mental QOL, suggesting a stronger link between self-reported fatigue and physical QOL. Janardhan and Bakshi36 determined that fatigue was independently associated with QOL and suggested that early detection and treatment of fatigue can improve QOL in people with MS. Amato et al.17 identified fatigue as an independent predictor of QOL in MS and demonstrated significantly high correlations between fatigue and physical (r = −0.66) and mental (r = −0.69) composite scores on the MSQOL-54. Although both of these studies reported a strong correlation between self-reported fatigue and QOL, they used a different measure to assess fatigue (Fatigue Severity Scale) in their samples. The present study demonstrated that people with MS who reported greater fatigue (a score of >10 on the MFIS-5) simultaneously exhibited impairments in physical as well as mental QOL compared with individuals who reported a score of 10 or less on the MFIS-5, thereby suggesting that a relationship between fatigue and QOL exists irrespective of the measurement instrument.

The present study also demonstrated that neurologic disability (EDSS) did not differ in people with MS who report high levels of fatigue compared with people with low levels of fatigue. These results indicate that the neurologic status of individuals with MS may not adequately predict the severity of fatigue experienced by them. These findings are consistent with previous work by Bakshi et al.,14 who found no significant relationship between fatigue (measured by the Fatigue Severity Scale) and EDSS score prospectively in a large sample of people with MS. Krupp et al.10 also demonstrated no significant associations between fatigue severity (measured by visual analogue scale) and EDSS score in people with MS.

Several limitations were identified in the present study. The retrospective and cross-sectional research study design limits formation of a cause-and-effect relationship between fatigue and other study variables. Thus, a prospective study elaborating on the effects of fatigue on different variables is warranted. An additional drawback of this study was that the study participants were not medically evaluated for other causes of fatigue (eg, anemia and hypothyroidism). However, the participants were screened by neurologists for significant medical conditions before their participation in the wellness program. This study used an abbreviated measure of fatigue (MFIS-5) that has not been well evaluated in MS. However, the short version was deduced from its parent version (the 21-item MFIS), which has been previously validated in MS. Another limitation of this study is that the participants were referred to and agreed to participate in a wellness and rehabilitation program and, therefore, may not be fully representative of the general MS population. Last, this study used separate Mann-Whitney U tests to determine between-group differences, which may have inflated the rate of type I error.

Conclusion

Fatigue was found to be a predominant symptom (>60%) in the study participants. Individuals reporting high levels of fatigue simultaneously exhibited greater impairments in performance-based and self-reported functional mobility, depression, and physical and mental QOL. These findings can be significant for appropriate assessment and management of an individual with MS presenting with complaints of fatigue. Neurologic disability, however, was not found to be associated with the level of fatigue experienced, suggesting that fatigue needs to be assessed in individuals with MS regardless of their disability level.

PracticePoints

- High levels of MS-related fatigue were found to be strongly associated with impairments in functional mobility, depression, and quality of life, which suggests that fatigue may influence other outcome measures in individuals with MS.

- This finding highlights the importance of including fatigue assessment in physical therapy evaluations and, therefore, may be useful for suitable management of individuals with MS presenting with complaints of fatigue.

References

1.MS Council for Clinical Practice Guidelines. Fatigue and Multiple Sclerosis: Evidence Based Management Strategies for Fatigue in Multiple Sclerosis. Washington, DC: Paralyzed Veterans of America; 1998.

2.Colosimo C, Millefiorini E, Grasso MG , et al. Fatigue in MS is associated with specific clinical features. Acta Neurol Scand. 1995;92:353–355.

3.Fisk J, Pontefract A, Ritvo P, Archibald C, Murray T. The impact of fatigue on patients with multiple sclerosis. Can J Neurol Sci. 1994;21:9–14.

4.Freal JE, Kraft GH, Coryell JK. Symptomatic fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1984;65:135–138.

5.Iriarte J, Subirá ML, Castro P. Modalities of fatigue in multiple sclerosis: correlation with clinical and biological factors. Mult Scler. 2000;6:124–130.

6.Trojan DA, Arnold D, Collet JP , et al. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: association with disease-related, behavioural and psychosocial factors. Mult Scler. 2007;13:985–995.

7.Kos D, Kerckhofs E, Nagels G, D'hooghe MB, Ilsbroukx S. Origin of fatigue in multiple sclerosis: review of the literature. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2008;22:91–100.

8.Kaminska M, Kimoff RJ, Schwartzman K, Trojan DA. Sleep disorders and fatigue in multiple sclerosis: evidence for association and interaction. J Neurol Sci. 2011;302:7–13.

9.Bergamaschi R, Romani A, Versino M, Poli R, Cosi V. Clinical aspects of fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Funct Neurol. 1997;12:247–251.

10.Krupp LB, Alvarez LA, LaRocca NG, Scheinberg LC. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:435–437.

11.Vercoulen JH, Hommes OR, Swanink CM , et al. The measurement of fatigue in patients with multiple sclerosis: a multidimensional comparison with patients with chronic fatigue syndrome and healthy subjects. Arch Neurol. 1996;53:642–649.

12.Blikman L, van Meeteren J, Horemans HL , et al. Is physical behavior affected in fatigued persons with multiple sclerosis? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:24–29.

13.Rietberg MB, van Wegen E, Uitdehaag B, Kwakkel G. The association between perceived fatigue and actual level of physical activity in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler J. 2011;17:1231–1237.

14.Bakshi R, Shaikh ZA, Miletich RS , et al. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis and its relationship to depression and neurologic disability. Mult Scler. 2000;6:181–185.

15.Chwastiak LA, Gibbons LE, Ehde DM , et al. Fatigue and psychiatric illness in a large community sample of persons with multiple sclerosis. J Psychosom Res. 2005;59:291–298.

16.Mohr DC, Hart SL, Goldberg A. Effects of treatment for depression on fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:542–547.

17.Amato MP, Ponziani G, Rossi F, Liedl CL, Stefanile C, Rossi L. Quality of life in multiple sclerosis: the impact of depression, fatigue and disability. Mult Scler. 2001;7:340–344.

18.Boosman H, Visser-Meily JMA, Meijer JWG, Elsinga A, Post MWM. Evaluation of change in fatigue, self-efficacy and health-related quality of life, after a group educational intervention programme for persons with neuromuscular diseases or multiple sclerosis: a pilot study. Disabil Rehabil. 2011:690–696.

19.Tellez N, Rio J, Tintore M, Nos C, Galan I, Montalban X. Does the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale offer a more comprehensive assessment of fatigue in MS? Mult Scler.2005;11:198–202.

20.Kos D, Kerckhofs E, Carrea I, Verza R, Ramos M, Jansa J. Evaluation of the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale in four different European countries. Mult Scler. 2005;11:76–80.

21.Rikli RE, Jones CJ. Senior Fitness Test Manual. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2001.

22.Cattaneo D, Regola A, Meotti M. Validity of six balance disorders scales in persons with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28:789–795.

23.Nilsagard Y, Lundholm C, Gunnarsson LG, Dcnison E. Clinical relevance using timed walk tests and “timed up and go” testing in persons with multiple sclerosis. Physiother Res Int. 2007;12:105–114.

24.Powell LE, Myers AM. The Activities-specific Balance Confidence (ABC) Scale. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50A:M28–M34.

25.Cattaneo D, Jonsdottir J, Repetti S. Reliability of four scales on balance disorders in persons with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29:1920–1925.

26.Hobart JC, Riazi A, Lamping DL, Fitzpatrick R, Thompson AJ. Measuring the impact of MS on walking ability: the 12-Item MS Walking Scale (MSWS-12). Neurology. 2003;60:31–36.

27.Learmonth VC, Dlugonski DD, Pilutti LA, Sandroff BM, Motl RW. The reliability, precision and clinically meaningful change of walking assessments in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler J. 2013;19:1784–1791.

28.Benedict RHB, Fishman I, McClellan MM, Bakshi R, Weinstock-Guttman B. Validity of the Beck Depression Inventory-Fast Screen in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2003;9:393–396.

29.Vickrey BG, Hays RD, Harooni R, Myers LW, Ellison GW. A health-related quality of life measure for multiple sclerosis. Qual Life Res. 1995;4:187–206.

30.Özakbas S, Akdede BB, Kösehasanogullari G, Aksan O, Idiman E. Difference between generic and multiple sclerosis-specific quality of life instruments regarding the assessment of treatment efficacy. J Neurol Sci. 2007;256:30–34.

31.Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983;11:1444–1452.

32.Morris M, Cantwell C, Vowels L, Dodd K. Changes in gait and fatigue from morning to afternoon in people with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72:361–365.

33.Feys P, Gijbels D, Romberg A , et al. Effect of time of day on walking capacity and self-reported fatigue in persons with multiple sclerosis: a multi-center trial. Mult Scler. 2012;18:351–357.

34.Cook KF, Alyssa M, Bamer AM , et al. Multiple sclerosis and fatigue. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2013;24:653–661.

35.Béthoux F. Fatigue and multiple sclerosis. Ann Readapt Med Phys. 2006;49:355–360.

36.Janardhan V, Bakshi R. Quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis: the impact of fatigue and depression. J Neurol Sci. 2002;205:51–58.