Examining the relationship between family caregivers’ emotional states and ability to empathize with patients with multiple sclerosis

Why is this important to me?

Caregivers of people with MS may experience a high psychological burden, which may be due to:

- Emotional distress

- Isolation

- Feelings of abandonment

- Economic problems

When a caregiver experiences negative emotions, the care provided to the person with MS may be less than ideal. A better understanding of empathy and the factors that negatively impact empathy may help healthcare professionals identify caregivers who may provide insufficient care of a family member with MS and allow the healthcare provider to direct the caregiver to sources of support.

What is the objective of this study?

Caregivers of a family member with MS answered questionnaires designed to assess their mood state (including anger, depression, fatigue, anxiety, and others), empathy (does the caregiver try to understand the patient’s feelings, worries, and patient’s perspective, and does the caregiver try to accept and understand the person with MS?), and their perception of the impact of MS on the daily life of the person with MS. It was observed that:

- 30% of caregivers had scores indicating distress in such areas as fatigue, anger, depression, and anxiety.

- A caregiver’s poor mood state, especially in the areas of anger, depression, anxiety, and confusion, was associated with the caregiver perceiving a greater impact of MS on his or her family member.

- A caregiver's mood state did not appear to change their feelings of empathy toward the MS patient.

- The MS patient's functional or cognitive status did not change the caregiver's level of empathy

These observations suggest that health care professionals should pay more attention to the emotional needs of caregivers. When these needs are not met and the caregiver’s mood worsens, reduced communication, poor coping, and less than ideal care of the person with MS may result. Distressed caregivers may need to be educated about treatment of mood problems and access to respite care. Healthcare providers should encourage caregivers to talk about the psychological and emotional impact of caring with someone with MS. If healthcare professionals can help caregivers to recognize areas of distress, they can help caregivers to address them and ensure they are better able to provide ideal care for their family member with MS.

How did the authors study this issue?

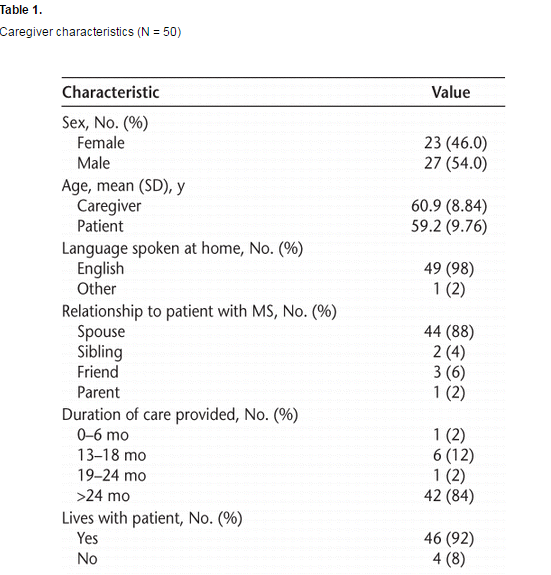

The authors enrolled 50 caregivers of people with MS (46% female) who were living in Manitoba, Canada. Caregiver participants were required to be the main caregiver of the person with MS and to have cared for the person for at least 6 months. Caregivers answered several questionnaires to assess mood, empathy, and perceived impact on the MS patient.

For other resources, visit:

Original Article

Examining the Relationship Between Family Caregivers' Emotional States and Ability to Empathize with Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: A Pilot Study

Internatinal Journal of MS Care

Sepideh Pooyania, MD; Michelle Lobchuk, RN, PhD; Wanda Chernomas, RN, PhD; Ruth Ann Marrie, MD, PhD

Background: Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common nontraumatic cause of disability affecting young adults in Canada. Caregivers of patients with MS are highly psychologically burdened. Empathy and helping behaviors are hallmarks of quality care, but when they are challenged, suboptimal patient care can result. We aimed to evaluate the prevalence of negative emotional states among primary caregivers of people with MS; the association between the caregiver's empathy-related behavior and the physical and cognitive impairment of the person with MS; and the association between the caregiver's emotional status and his or her empathy-related behaviors.

Methods: We conducted a descriptive, cross-sectional pilot study with family caregivers of noninstitutionalized individuals living with MS. We used univariate linear regression models for each potential predictor. The Kruskal-Wallis test was conducted to compare differences in caregiver empathic responses depending on Profile of Mood States subscale scores.

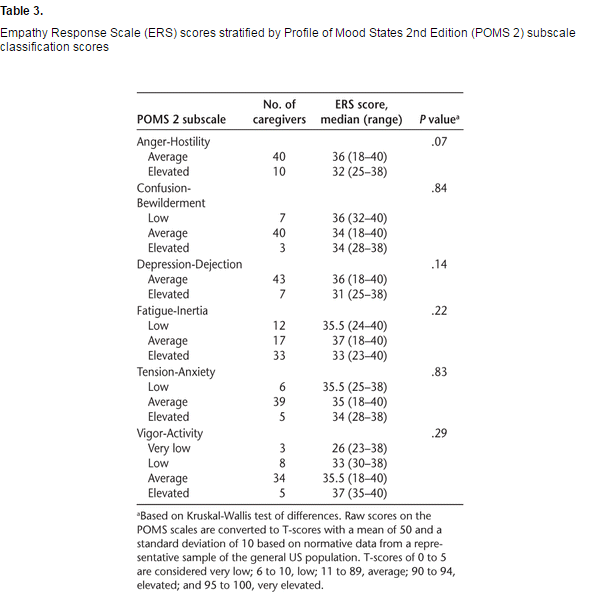

Results: Thirty percent of caregivers had elevated or very elevated mood scores, and such elevated scores were associated with greater functional impact of MS on the person with MS. Patient severity of cognitive impairment was not associated with caregiver mood scores. Caregiver mood state was not associated with empathy-related behaviors. Empathy-related behaviors were less frequent when levels of anger and hostility were higher, but this association did not reach statistical significance.

Conclusions: Given the elevated levels of fatigue, depression, and anger observed among caregivers in this study, clinicians need to be aware of the potential impact of caregiving and to assess the needs of caregivers.

Compared with other world regions, Canada has a particularly high incidence and prevalence of multiple sclerosis (MS).1–3 MS is the most common nontraumatic cause of disability affecting young adults in Canada, and it manifests with a broad range of symptoms, including vision loss, weakness, sensory disturbance, bowel or bladder dysfunction, and impaired mobility.4 Assistance from informal caregivers, such as family members, friends, and neighbors, enables people with MS to remain in their homes as their functional dependence becomes more permanent and their need for personal assistance increases with the progression of physical and cognitive disabilities.5,6

Previous studies have shown that caregivers of patients with MS are highly psychologically burdened, with consequent reduced quality of life.7 Other negative effects of MS on families include emotional distress, isolation, feelings of abandonment, and economic difficulties. At the same time, being in a family with a member who has been diagnosed as having MS can deepen relationships, encourage feelings of accomplishment and pride, and improve coping skills.7 Findings in other disease contexts suggest that the provision of optimal informal care by families is driven by empathy-related processes that may be challenged when caregivers experience negative emotions. Empathy theory8 proposes that empathy-related processes are influenced by motivating factors (eg, the degree of suffering or deficits experienced by the affected person) and that inhibiting factors can detract from the caregiver's motivation to expend mental energy to engage in empathy toward the patient (eg, caregiver mood states). In one study, when individuals with lung cancer continued to smoke cigarettes, caregivers reported more blame and anger and fewer empathy-related helping behaviors toward the affected person.9 Empathy and helping behaviors are hallmarks of quality care, but when they are challenged, caregiver confidence can be diminished, resulting in unsafe, poorly timed, and suboptimal care of the patient.8

A better understanding of empathy and the factors that negatively influence empathy-related processes is relevant to clinicians. Enhanced awareness of these issues may improve the sensitivity of identification of families at risk for suboptimal empathic responses toward patients as they deal with cognitive and functional deficits related to MS. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate 1) the prevalence of negative emotional states among primary caregivers of individuals with MS; 2) the association between the caregiver's empathy-related behavior and the physical and cognitive impairment of the person with MS; and 3) the association between the caregiver's mood or emotional status and his or her empathy-related behaviors.

Methods

This descriptive, cross-sectional pilot study was conducted with a convenience sample of family caregivers of noninstitutionalized individuals living with MS in Manitoba, a central Canadian province. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Manitoba Health Research Ethics Board and the Winnipeg Health Sciences Centre (Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada).

Inclusion Criteria

Eligible participants were recruited from the population-based provincial MS Clinic at the Winnipeg Health Sciences Centre. Consecutive potentially eligible caregivers were approached by a research assistant at the time of clinic visits. To be included in the study, family caregivers had to 1) identify themselves as the primary caregiver of the medically diagnosed individual with MS, 2) speak and read English, and 3) care for the individual with MS for at least 6 months before participation in the study to allow the caregiver sufficient time to develop realistic ideas about the patient's deficit and the amount of care he or she might need.

Study Instruments

After informed consent was obtained, a research assistant provided the study instruments to the family caregiver participant. The instruments included a brief investigator-developed demographic tool with questions about the family caregiver's sex, language spoken at home, relationship to the person with MS, how long they had been the caregiver, and if they lived or did not live with the patient; the Profile of Mood States 2nd Edition (POMS 2)10–12; the Empathic Responding Scale (ERS)13; the 29-item Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29)14,15; and the Multiple Sclerosis Neuropsychological Screening Questionnaire (MSNQ).16,17

The POMS 2 is a 35-item, 5-point interval scale self-report questionnaire that was used to capture the caregiver's mood status during the past week.10 Previous work has indicated that the POMS 2 is a reliable and valid tool.11 For each item, higher scores indicate worse mood states: 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). Scores on each item are summed to generate a raw score. Raw scores are converted to T-scores with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10 based on normative data from a representative sample of the general US population. T-scores of 0 to 5 are considered very low; 6 to 10, low; 11 to 89, average; 90 to 94, elevated; and 95 to 100, very elevated. The POMS subscales include Anger-Hostility, Confusion-Bewilderment, Depression-Dejection, Fatigue-Inertia, Tension-Anxiety, and Vigor-Activity.12 Friendliness may be captured as a separate item, although this was not evaluated in this study because the focus was on factors that may adversely affect empathy. The Total Mood Disturbance score is an index of overall distress that is obtained by summing all subscale scores minus the Vigor-Activity score. The ERS is a 10-item, 5-point interval scale that captures empathic responses toward the patient with a Cronbach internal consistency reliability estimate of α = 0.93.13 The ERS questions focus on the caregiver's perspective regarding empathic behaviors. Specifically, does the caregiver try to understand the patient's concerns and feelings, as well as the patient's perspective, and does the caregiver try to accept and assist the patient? For example, “I try to imagine myself in the patient's shoes” or “I try to comfort the patient by telling him or her about my positive feelings for him or her.” The ERS scores range from 0 (does not describe me well) to 4 (does describe me well).

The MSIS-2914,15 is a 29-item scale that was used to capture the caregiver's perception of the functional impact of MS on the day-to-day life of the person for whom they were providing care. When used with proxy respondents, the Cronbach reliability estimate was α > 0.96, with high scale test-retest reliability (interrater correlation coefficient of 0.87). The MSIS-29 has moderate internal validity, with an intercorrelation of 0.65.15 The caregiver's perception of the patient's cognitive deficits was captured using the MSNQ, a 15-item instrument that is a valid, sensitive measure of cognitive impairment in MS when completed by proxy respondents. It has high internal consistency reliability (Cronbach α < 0.91) when used with family proxies.16,17

The target sample size was 50. Sample size calculations for the regression models were based on the expected variance explained by the predictors of the caregiver's empathy-related behavior (ie, patient's functional deficits from the caregiver's perspective and the caregiver's self-report of his or her psychological or emotional status), as measured by the r2 statistic. It was thought that an r2 of 0.20 detected in this pilot study would be sufficient to warrant further study. Power was set at 0.80, and type I error was set at 0.05. Because this was a pilot study, we did not adjust for multiple comparisons.18

Analysis

Continuous variables are described using means (SDs) or medians (interquartile ranges) as appropriate. Categorical variables are described as frequencies (percentages). We assessed associations among ordinal-level variables captured on the ERS, the MSIS, the MSNQ, and the POMS total and subscale scores using bivariate Spearman rho correlations. Relationships among the POMS total score and MSIS and MSNQ total scores were visually assessed using scatterplots and were quantified using Pearson correlation coefficients. To determine whether physical impairment (MSIS total score) and cognitive impairment (MSNQ total score) of the person with MS and the mood state of the caregiver (POMS total score) could predict caregivers' empathy-related behaviors (ERS total score), we created univariate linear regression models for each potential predictor. For each model, we report regression coefficients and the R2. Scatterplots found no obvious departures from linearity or substantial outliers. Model residual diagnostics were evaluated via histograms and Q-Q plots. Cook's distance was calculated to assess the influence of each participant. Because the outcomes of interest were skewed and this would violate the normality assumption required for the analysis of variance procedure, the Kruskal-Wallis test was conducted to compare differences in the physical and cognitive impairment of the patient with MS and caregiver empathic responses depending on POMS subscale scores. The POMS subscale classifications “elevated” and “very elevated” were combined for this analysis due to small group sizes. Associations between the POMS total score and the MSIS and MSNQ total scores were visually assessed using scatterplots and were quantified using Pearson correlation coefficients. A statistical software program (SAS version 9.3; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) was used for all the analyses.

Results

Of 142 caregivers who were screened, 55 (38.7%) were ineligible. Forty-two of the patients lived independently, eight lived in a nursing home, and five had only home care. Therefore, those 55 caregivers were not primary caregivers. Of the remaining caregivers (n = 87), 54 (62.1%) consented to participate. The 33 caregivers who declined to participate in the study did so mostly due to lack of interest and time. Of those who consented, 50 caregivers (92.6%) returned completed forms after being sent at least three reminders.

Of the 50 caregiver participants, 23 (46%) were women. The mean (SD) age of caregivers was 60.9 (8.84) years and of individuals with MS was 59.2 (9.76) years. Most caregivers were the spouse of the patient, lived with the patient, and had cared for the patient for more than 24 months (Table 1).

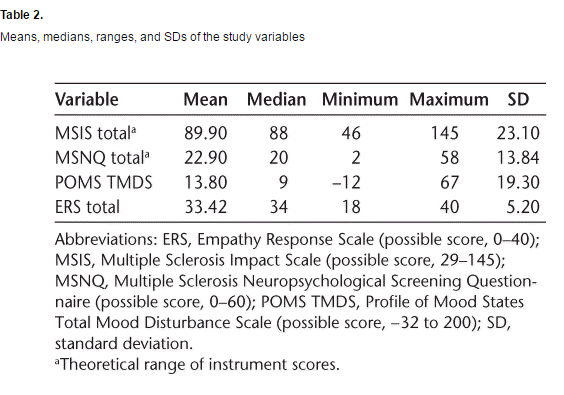

With respect to the total mood score, 15 family caregiver participants (30%) had elevated or very elevated scores. With respect to mood subscale scores, elevated or very elevated scores were highest for the Fatigue-Inertia subscale (n = 21, 42%), followed by the Anger-Hostility (n = 10, 20%), Depression-Dejection (n = 7, 14%), Tension-Anxiety (n = 5, 10%), and Vigor-Activity (n = 5, 10%) subscales. The prevalence of elevated scores was the lowest on the Confusion-Bewilderment (n = 3, 6%) subscale. Table 2 provides descriptive statistics regarding the questionnaires used in this study.

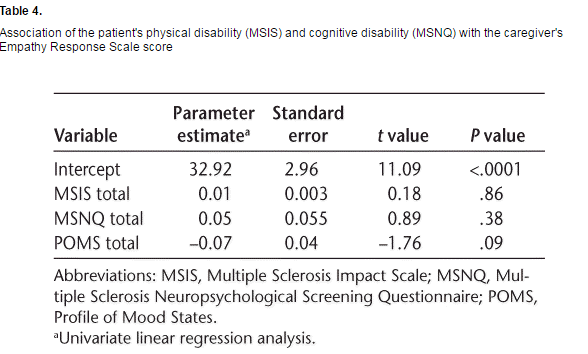

With respect to the relationship between the caregiver's emotional status and empathy-related behaviors, we did not observe any statistically significant associations; however, lower total ERS scores among caregivers approached a significant association with higher levels of caregiver distress on the POMS Anger-Hostility subscale (P = .07) (Table 3). The simple linear regression results did not reveal any associations between the patient's functional status, the patient's cognitive state, or the family caregiver's mood states and the caregiver's total ERS score (Table 4).

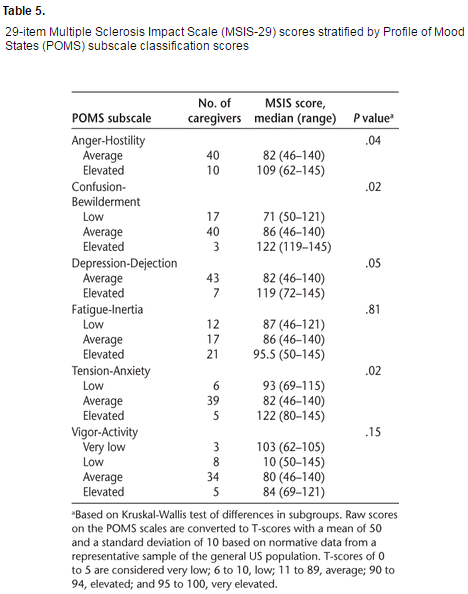

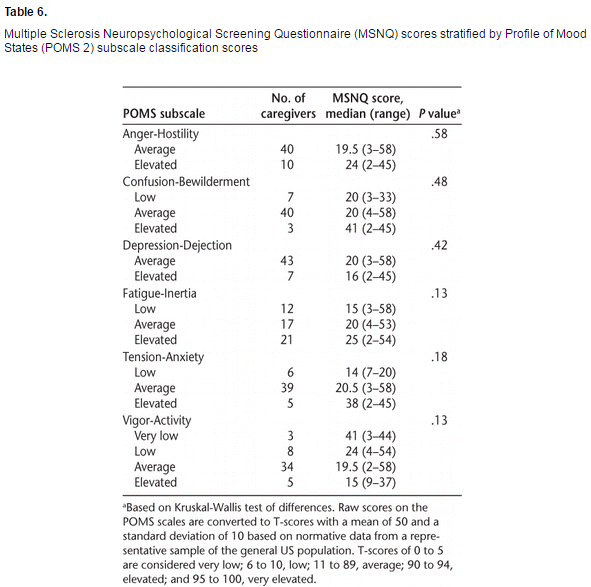

We also evaluated whether the patient's functional and cognitive status had a differential effect on the caregiver's psychological or emotional status (Tables 5 and 6). We found that greater functional impact of MS on patients (as perceived by caregivers) was associated with higher POMS total scores of caregivers (r = 0.32, P = .027). We also observed associations between POMS subscale scores and functional impact of MS. Elevated or very elevated scores on the Anger-Hostility, Depression-Dejection, Tension-Anxiety, and Confusion-Bewilderment subscales were associated with caregivers reporting that the person with MS experienced greater functional impact (Table 5). No differences were found in POMS subscale scores depending on the caregiver's report of the patient's cognitive status (Table 6).

Discussion

Given the prominent role of the caregiver in chronic diseases, it is important to understand factors that negatively affect the empathic behaviors of caregivers and their ability to support individuals dealing with chronic diseases such as MS. To our knowledge, this is the first study in which investigators aimed to conduct a preliminary examination of relationships between patient functional or cognitive status and negative caregiver mood states and empathic responses of caregivers in MS. Although empathy-related behaviors were less frequent when levels of anger and hostility were higher, this did not reach statistical significance, possibly due to the small sample size.

Regarding the prevalence of caregivers' negative mood states in this study, fatigue, anger, and depression were reported as most distressing to caregivers. Forty-two percent of the caregivers expressed that their most elevated mood disturbance was related to fatigue-inertia. Other studies have found that fatigue is a common complaint of caregivers of patients with MS.7 We did not capture caregivers' perceptions of burden, and we were unable to examine the relationship of burden to perceived fatigue, unlike previous work. Anger was reported by 20% of this study's caregivers. Other researchers19 have described anger in relation to the “crisis” of relapses in MS that disrupt the quality of life of caregivers owing to unpredictable outcomes, resulting in caregivers' reactions of anger, grief, guilt, and anxiety. Caregivers' anger has been explained in relation to their perceived inability to control one's life and disruption to one's priorities or plans in life.20 Whereas depression was reported by 16% of this study's sample of caregivers, others have reported prevalence as high as 77%.

The present analyses revealed that 30% of caregivers had elevated or very elevated mood scores and that elevated scores on the Anger-Hostility, Depression-Dejection, Tension-Anxiety, and Confusion-Bewilderment subscales were associated with greater functional impact of MS on the person receiving care. Patients' severity of cognitive impairment was not associated with caregivers' mood scores. Coping problems or negative feelings held by family caregivers have been linked to negative perceptions of accomplishment5 and to challenges in sensitive communication between affected individuals that pose as barriers to creative decision making, problem solving, and engagement in optimal care. The deleterious impact of caregivers' anxiety and depression has also been linked to caregivers' negative perceptions of the physical impact of MS on affected individuals (or caregiver overestimation of the disease impact score).21 In conjunction with the findings from the present study, this suggests that more attention needs to be given by health-care professionals to the social and emotional needs of caregivers, who report elevated levels of fatigue, anger, and depression that are likely due to the burden of taking care of a patient with MS and that, in turn, pose a hazard to optimal communication, coping, care, and assessment of the impact of MS on the affected individual.

We did not find that the caregiver's mood state, the patient's cognitive status, or the patient's functional status was associated with empathy-related behaviors of caregivers. We discovered one finding that approached statistical significance where higher levels of caregiver anger and hostility were linked to fewer empathy-related responses toward the individual affected by MS. In a related study of couples dealing with MS, changes in physical intimacy (due to sexual dysfunction, fatigue, or bladder or bowel dysfunction) and poor coping strategies were found to negatively affect sensitive, empathic communication, consequently leading to dysfunctional problem solving and shared decision making and suboptimal care.19 In a non-MS context, other researchers found in their sample of 302 pairs of caregivers and care recipients that when caregivers experienced more anger, they also engaged in fewer empathy-related behaviors toward the person with lung cancer.9 It is difficult to compare the results of this study with those of other studies in MS that have focused on predictors of caregiver burden rather than on caregiver empathy.

A discussion of limitations is warranted. Owing to this pilot study's small sample, a caveat is warranted regarding preliminary findings of associations between patient functional status and caregiver mood states. Almost 38% of eligible caregivers did not consent to participate in the study. Those who agreed to participate might have been more willing because they were experiencing more distressing mood states or more challenges in their empathic communication with individuals affected by MS than those who did not participate. Although a consecutive sample is easier to use, and ensures that all potentially eligible participants are approached, there may be variations in the characteristics of individuals attending the MS Clinic at different times of the year; thus, this approach may also reduce the generalizability of the findings. We found that the mean ERS score for caregivers was high, with limited variability in empathic responses, possibly because most participants were long-term caregivers. Most caregivers in this sample reported that they cared for the individual with MS for more than 24 months. The familiarity of coping or dealing with MS may have had a positive influence on caregivers' responses. If we had also included a measure of the caregiver's positive mood states, rather than focusing solely on negative mood states, we could have examined potential factors, such as friendliness, that positively affect empathic responding by long-term family caregivers of individuals with MS. These results may have been different if the caregiver sample had been in the early stages of dealing with MS. We did not adjust for multiple comparisons because this was a pilot study and we did not want to risk failing to identify a potentially important finding deserving of future study. However, this increased the risk of potentially spurious findings. Furthermore, perspectives from both the person with MS and the caregiver on the impact of MS on the affected individual's cognitive and functional status would have provided additional insights about potential predictors of caregivers' empathic responses. However, this pilot study provides valuable insight into the design of future studies on this topic. Given the large proportion of caregivers who were not eligible, and the large proportion who declined to participate, achieving the necessary sample sizes would preferably involve more than one center. We approached caregivers in the clinic, at a time when they may have been fatigued or under stress related to the visit. Approaching caregivers at alternative times or offering alternative methods of completing questionnaires, such as online completion, would also be worth exploring.

Conclusion

This pilot study identified several clinically relevant issues. Given the elevated levels of fatigue, depression, and anger observed among caregivers in this study, clinicians need to be aware of the potential impact of caregiving on caregivers and to assess caregiver needs. Improving the emotional status of caregivers may require education, treatment of mood problems, access to respite care, and other interventions. Caregivers should be encouraged by clinicians to voice the emotional or psychological impact or challenges that they are experiencing in the caregiving role. There remains a need for larger, longitudinal studies on the impact of caregivers' and affected individuals' perceptions of patient functional deficits, cognitive status, and caregiver mood state effects, such as anger-hostility, on caregivers' empathic responses toward individuals living with MS.

PracticePoints

- Previous studies have shown that caregivers of patients with MS are highly psychologically burdened, with consequent reduced quality of life. Findings in other disease contexts suggest that the provision of optimal informal care by families is driven by empathy-related processes that may be challenged when caregivers experience negative emotions.

- A better understanding of empathy and the factors that negatively influence empathy-related processes is relevant to clinicians. Enhanced awareness of these issues may improve the sensitivity of identification of families at risk for suboptimal empathic responses toward patients as they deal with cognitive and functional deficits related to MS.

- Given the elevated levels of fatigue, depression, and anger observed among caregivers in this study, clinicians need to be aware of the potential impact of caregiving on caregivers and to assess their needs. Improving the emotional status of caregivers may require education, treatment of mood problems, access to respite care, and other interventions.

References

1.Evans C, Beland S, Kulaga S, et al. Incidence and prevalence of multiple sclerosis in the Americas: a systematic review. Neuroepidemiology. 2013;40:195–210.[CrossRef]

2.Multiple Sclerosis International Federation. Atlas of MS 2013: Mapping Multiple Sclerosis Around the World. London, UK: Multiple Sclerosis International Federation; 2013.

3.Makhani N, Morrow SA, Fisk J, et al. MS incidence and prevalence in Africa, Asia, Australia, and New Zealand: a systematic review. Mult Scler Relat Disord.2014;3:48–60. [CrossRef]

4.Noseworthy JH, Lucchinetti C, Rodriguez M, Weinshenker BG. Multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:938–952. [CrossRef]

5.Buchanan RJ, Huang C. Caregiver perceptions of accomplishment from assisting people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34:53–61. [CrossRef]

6.Opara J, Jaracz K, Brola W. Burden and quality of life in caregivers of persons with multiple sclerosis. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2012;46:472–479.

7.Uccelli MM. The impact of multiple sclerosis on family members: a review of the literature. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2014;4:177–185. [CrossRef]

8.Davis M. Empathy: A Social Psychological Approach. Madison, WI: Brown and Benchmark; 1994.

9.Lobchuk MM, McClement SE, McPherson CJ, Cheang M. Impact of patient smoking behavior on empathic helping by family caregivers in lung cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2012;39:E112–E121. [CrossRef]

10.McNair DM, Lorr M. An analysis of professed psychotherapeutic techniques. J Consult Psychol. 1964;28:265–271. [CrossRef]

11.Nyenhuis DL, Yamamoto C, Luchetta T, Terrien A, Parmentier A. Adult and geriatric normative data and validation of the profile of mood states. J Clin Psychol.1999;55:79–86. [CrossRef]

12.Heuchert JP, McNair DM. POMS-2 Manual: A Profile of Mood States. 2nd ed. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems Inc; 2012.

13.O'Brien TB, DeLongis A. The interactional context of problem-, emotion-, and relationship-focused coping: the role of the big five personality factors. J Pers.1996;64:775–813. [CrossRef]

14.Hobart J, Lamping D, Fitzpatrick R, Riazi A, Thompson A. The Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29): a new patient-based outcome measure. Brain.2001;124(pt 5):962–973. [CrossRef]

15.van der Linden FA, Kragt JJ, Klein M, van der Ploeg HM, Polman CH, Uitdehaag BM. Psychometric evaluation of the multiple sclerosis impact scale (MSIS-29) for proxy use. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:1677–1681. [CrossRef]

16.Benedict RH, Cox D, Thompson LL, Foley F, Weinstock-Guttman B, Munschauer F.Reliable screening for neuropsychological impairment in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2004;10:675–678. [CrossRef]

17.Benedict RHB, Munschauer F, Linn R, et al. Screening for multiple sclerosis cognitive impairment using a self-administered 15-item questionnaire. Mult Scler.2003;9:95–101. [CrossRef]

18.Rothman KJ. No adjustments are needed for multiple comparisons. Epidemiology.1990;1:43–46. [CrossRef]

19.Buchanan RJ, Huang C. Informal caregivers assisting people with multiple sclerosis: factors associated with the strength of the caregiver/care recipient relationship. Int J MS Care. 2011;13:177–187. [Abstract]

20.Kalb R. The emotional and psychological impact of multiple sclerosis relapses. J Neurol Sci. 2007;256(suppl 1):S29–S33. [CrossRef]

21.Sonder JM, Balk LJ, Bosma LV, Polman CH, Uitdehaag BM. Do patient and proxy agree? long-term changes in multiple sclerosis physical impact and walking ability on patient-reported outcome scales. Mult Scler. 2014;20:1616–1623. [CrossRef]

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Marrie has conducted clinical trials for Sanofi-Aventis. Drs. Pooyania, Lobchuk, and Chernomas have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/Support: The study was funded by the Riverview Health Centre (Susan's MS Research Fund), Research Manitoba (to SP), and a Don Paty Career Development Award from the MS Society of Canada (to RAM).