Switching or Discontinuing Disease-Modifying Therapies for MS

Why is this study important to me?

It is extremely important that patients and physicians have good communication, and openly participate in shared-decision making concerning MS disease-modifying therapies. Circumstances might arise in which the patient or the physician considers the option of discontinuing DMT, but both should recognize the need for much more data about the likelihood of success. Steps should be taken to minimize both adverse events and the risk of recurrent disease. Whether DMT can ever be purposely discontinued without incurring a significant risk of disease recurrence remains to be determined.

What was the objective of this article?

Most neurologists recommend a disease-modifying therapy (DMT) for their patients with relapse-remitting MS, or clinically isolated syndrome. However, there are times when discontinuation of DMTs may occur.

This article reviews the reasons for discontinuation or switching of DMT, as well as procedures that might lessen risk to the patient under such circumstances. This article also addresses the question of whether a physician might recommend discontinuation of DMT in a patient with prolonged disease stability.

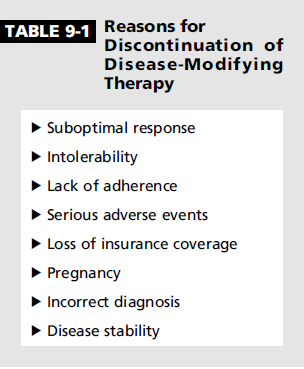

Possible reasons for discontinuing DMT:

- Lack of efficacy. A continuing or worsening of disease activity can prompt consideration of changing therapy.

- Pregnancy, or attempting to conceive. Most currently available DMTs should be discontinued during, and preferably before, pregnancy.

- Inadequate adherence to the treatment regimen. A patient’s failure to adhere to the correct regimen may for various reasons may render the treatment ineffective.

- Disease Stability. An absence of disease activity (5+ years) may prompt either the patient or the physician to question the continued need for DMT. There is little information on this approach, a few investigators have begun to broach the subject.

- Incorrect diagnosis of MS. DMT must be discontinued if it is discovered that a patient was misdiagnosed with MS

Additional reasons may include:

- Troublesome side effects.

- Serious adverse events

- Loss of insurance coverage

- Patient having other form of MS - either secondary or primary progressive

How did the authors study this issue?

The author reviewed recent literature, as well as relied on his extensive clinical experience, in examining the various reasons behind the discontinuation of multiple sclerosis disease-modifying therapies.

| SHARE: | |||||

Original Article

Switching or Discontinuing Disease-Modifying Therapies for Multiple Sclerosis

Aaron E. Miller, MD, FAAN

Continuum

ABSTRACT

Purpose of Review: This article reviews the reasons for discontinuation or switching of multiple sclerosis disease-modifying therapy as well as procedures that might mitigate risk to the patient under such circumstances.

Recent Findings: Recent review of the literature, as well as the author’s extensive clinical experience, indicate that the discontinuation of multiple sclerosis disease-modifying therapies occurs for many reasons. Often one medication is stopped at the recommendation of the physician in order to switch to another medication. However, often the decision to discontinue medication is made by the patient. Unfortunately, in still other situations, treatment is stopped because of circumstances beyond the control of either patient or physician (eg, a loss of insurance coverage). Currently available data do not permit a conclusion about whether it is ever safe to discontinue disease-modifying therapy in a stable patient without the expectation of return of disease activity.

Summary: Clinicians must help patients avoid unnecessary and undesirable cessation of disease-modifying therapy. While switches of therapy are often necessary, steps to minimize both adverse events and the risk of recurrent disease should be undertaken. Whether disease-modifying therapy can ever be purposely discontinued without incurring a significant risk of disease recurrence remains to be determined.

INTRODUCTION

Among the reasons a physician may advise a patient with multiple sclerosis (MS) to discontinue a particular therapy (often to be replaced by an alternate medication) are lack of efficacy, troublesome adverse events, an attempt at conception or actual pregnancy, inadequate adherence to the treatment regimen, or even recognition of erroneous diagnosis (Table 9-1). This article also addresses the question of whether a physician might recommend discontinuation of disease-modifying therapy in a patient with prolonged disease stability while taking the medication.

Patients may discontinue disease-modifying therapies, unfortunately sometimes without informing their physicians, because of intolerable adverse events. In addition, psychological factors may interfere with a patient’s desire or ability to continue taking a particular medication or even any disease-modifying therapy at all.

DO ALL PATIENTS WITH MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS OR AT HIGH RISK FOR MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS NEED TO BEGIN DISEASE-MODIFYING THERAPY?

In the United States, most neurologists generally recommend the initiation of disease-modifying therapy for virtually all patients with relapsing forms of MS. In addition, most American neurologists with expertise in MS advise patients with a first neurologic episode characteristic of MS who also have brain MRI lesions (often referred to as clinically isolated syndrome) to start treatment. This recommendation is based on the results of several randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trials including all the currently available injectable disease-modifying therapies1–4 (except pegylated interferon beta-1a) and one oral agent, teriflunomide.5 Each study demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in the conversion to definite MS. Nonetheless, in many countries outside the United States this is not usual practice, and some American neurologists continue to defer treatment until criteria for definite MS are satisfied.

Inference from modern phase 3 trials suggests that patients with milder disease are being entered into studies and presumably are more frequently treated in clinical practice. The fact that relapse rates among patients in the placebo arms of clinical trials conducted in the 21st century are appreciably lower than among patients in trials conducted in the late 1980s and 1990s supports this notion. The remarkably low relapse rates among patients in the active arms in these more recent trials suggests that milder disease is easier to control. This raises the question, indeed, of whether all patients with MS need such early treatment. Very early treatment of patients with mild disease will, almost inevitably, increase the likelihood that after a period of time with no disease activity evident, the issue of discontinuing therapy will more often be raised. This question will be addressed further later in this article.

DISCONTINUING THERAPY BECAUSE OF SUBOPTIMAL RESPONSE

Currently, even the most effective therapy for relapsing forms of MS fails to completely eliminate disease activity in most patients. Continuing disease activity inevitably prompts consideration of changing therapy, which, in present treatment paradigms, almost always means discontinuing the medication the patient is currently taking rather than adding another agent. A discussion about the decision-making process for which therapy to switch to is beyond the scope of this article and is addressed further in the articles “Early Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis” by David E. Jones, MD,6 and “Severe, Highly Active, or Aggressive Multiple Sclerosis” by Mark S. Freedman, MSc, MD, FAAN, FRCPC, and Carolina A. Rush, MD, FRCPC,7 in this issue of Continuum. Suffice it to say that a pattern of recurring disease activity or new severe disease activity will likely result in a switch of therapy. The timing of initiation of the replacement disease-modifying therapy depends, at least in part, on the mechanism of action and duration of effect of the medication that is being stopped as well as on the nature of the effects of the subsequent treatment. Unfortunately, the subject of timing of initiation of a replacement medication has been studied very little, so many of the following recommendations represent the author’s own practice, based on what little information has been published or presented, as well as on discussions with colleagues. In general, initiation of a new agent should be done as quickly as deemed safely possible to minimize the period of time in which a patient is not receiving the potential benefit of disease-modifying therapy.

When initiating a new therapy, baseline laboratory studies should be obtained, generally including complete blood count and hepatic panel. In addition, obtaining a new baseline brain MRI (some might add cervical spine MRI) is advisable. This is often obtained a few months after beginning the new disease-modifying therapy because disease activity occurring relatively soon after the new treatment has been initiated would not usually be considered as evidence of failure to respond to the new agent.

Switching From Interferons or Glatiramer Acetate

Based on their respective mechanisms of action, switching from interferons or glatiramer acetate does not appear to warrant any washout period. Any new agent may be initiated as soon as feasible.

Switching From Fingolimod

Very little information is available to guide the timing of initiation of a new treatment after discontinuation of fingolimod. Because the putative mechanism of action of fingolimod involves the trapping of lymphocytes in peripheral lymphoid organs, the circulating absolute lymphocyte count in patients on this medication is often quite low.8 It remains uncertain whether waiting for the lymphocyte count to rise before beginning the subsequent treatment provides any safety advantage. However, this might be a prudent course of action when switching to another agent that might sometimes depress lymphocyte numbers, albeit by a different mechanism, such as dimethyl fumarate or teriflunomide. However, the time course of the return to normal lymphocyte counts is uncertain and variable,9 so this waiting strategy could expose the patient to a prolonged period without benefit of treatment. Conversely, the mechanism of action of natalizumab, an agent to which patients having a suboptimal response to fingolimod are often switched, involves a blockage of the entrance of circulating lymphocytes into the central nervous system and, hence, typically results in a mild lymphocytosis. From this point of view, little would seem to be gained by a strategy of delaying initiation of natalizumab after discontinuing fingolimod. Whether early initiation of natalizumab in a patient whose lymphocyte count is depressed might increase the risk of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy is completely unknown and, if true, would likely be significant only in patients with antibodies to JC virus, the causative agent.

Switching From Teriflunomide

Teriflunomide undergoes enterohepatic circulation and is excreted very slowly, requiring an average of 8 months and as long as 2 years for complete elimination. Thus, under certain circumstances, an accelerated elimination procedure must be employed.10 This usually involves the administration of cholestyramine 3 times a day for 11 days (and levels of teriflunomide should be measured) or, alternatively, the use of activated charcoal. This would specifically be required in the case of pregnancy or desire for conception or in the circumstance of allergic response to the medication. Teriflunomide has undergone phase 2 trials in combination with both interferon11 and glatiramer acetate,12 which showed an advantage to the addition of teriflunomide. As no unusual safety signals were encountered in the combination arms, if a patient is switched from teriflunomide to one of the injectable agents, the use of the accelerated elimination procedure appears to be unwarranted. Based on their respective mechanisms of action, initiating natalizumab without an accelerated elimination procedure and without a washout period seems to show little risk, but no data are available. On the other hand, the initiation of natalizumab without using the accelerated elimination procedure might be considered to be counter to the prescribing information for natalizumab, which counsels against the use of the agent in combination therapy.13 The theoretical possibility that the persistence of teriflunomide could potentiate the lymphopenia associated with fingolimod and, less often, with dimethyl fumarate, might warrant consideration of an accelerated elimination procedure for teriflunomide if a switch to one of the alternative oral agents is contemplated.

Switching From Dimethyl Fumarate

Little information is available to guide recommendations for initiation of alternative therapy after discontinuation of dimethyl fumarate. The mechanism of action of this drug is uncertain, with an antioxidant effect based on activation of the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf-2) pathway the leading postulate.14 This would not seem cause for concern about the rapid initiation of another medication. However, dimethyl fumarate does, at times, have a lymphopenic effect, which might prompt a delay in beginning another drug that depresses lymphocyte counts. Unfortunately, it may take many weeks for the lymphocyte count to return to normal after dimethyl fumarate is stopped, which could cause a hazardous delay in introduction of the new disease-modifying therapy.

Switching From Natalizumab

Natalizumab is a monoclonal antibody directed against very late antigen-4 (VLA-4) (α4β1), an adhesion molecule on the surface of lymphocytes. The antibody presumably prevents the interaction of the adhesion molecule with its complementary receptor molecule VCAM-1 on the vascular endothelium, thereby preventing entrance of the cells into the central nervous system.15 Although the antibody appears to block the adhesion molecule for at least 2 months and perhaps a bit longer, based on its mechanism of action, it does not appear to be logical to defer initiation of another therapy if a switch is deemed appropriate. Although earlier practice often involved delaying several months before initiation of new therapy, recent data suggest that this practice is more likely to be associated with return of disease activity and sometimes with what appears to be excessive activity above what was expected from the prenatalizumab treatment period (so-called rebound). Studies with a switch to fingolimod, perhaps the most frequently administered therapy when a change from natalizumab has been made (often because of JC virus antibody positivity rather than suboptimal response to natalizumab), suggest that a better strategy would be to initiate the alternative therapy much earlier.16–18 Many MS subspecialists now recommend a washout period of not more than about 2 months when switching from natalizumab to another disease-modifying therapy.

DISCONTINUING DISEASE-MODIFYING THERAPY BECAUSE OF PREGNANCY OR ATTEMPTED CONCEPTION

As MS is commonly and, in fact, increasingly a disease of women, many of whom are of childbearing age, the issue of management of disease-modifying therapy in relation to pregnancy is very important. Ideally, but unrealistically, all pregnancies in women with MS would be planned, and drug discontinuation would occur in a well-reasoned and timely fashion. All reproductive issues, including management of disease-modifying therapies, should be thoroughly discussed with female patients, preferably including their partners, well in advance of pregnancy planning. Most currently available disease-modifying therapies should be discontinued during, and preferably before, pregnancy. A possible exception, in the author’s opinion, is glatiramer acetate. In the currently used system of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), glatiramer acetate has a Category B pregnancy rating, indicating no evidence of risk to the fetus in either humans or experimental animals, but with no specific testing having been conducted in pregnant women. I counsel women that they might consider remaining on glatiramer acetate while they attempt to conceive and even during the pregnancy. Most of my patients in these circumstances have elected to remain on glatiramer acetate while attempting to become pregnant, and the majority of these have also stayed on the medication throughout pregnancy. I have not encountered problems with this approach, nor has a pregnancy registry implicated increased problems for the babies of mothers who became pregnant while taking glatiramer acetate.19–21

Interferons, which carry a Category C pregnancy rating, also appear to convey little, if any, increased risk of fetal malformation.22,23 However, studies have indicated an increased risk of spontaneous abortion in experimental animals receiving interferon. Whether this is true in humans is uncertain because of inconsistent data. Although most neurologists likely recommend discontinuation of interferons for 1 to 2 months before the woman attempts conception, some recommend the continuation of medication until pregnancy is confirmed to avoid a prolonged period without disease-modifying therapy should conception not occur quickly.

Fingolimod24 and dimethyl fumarate9 have Category C pregnancy ratings, and both have been associated with fetal abnormalities in experimental animals. As these drugs are small molecules, they cross the placenta and are best avoided during pregnancy. No clear guidance based on data can be given about the washout period for these drugs prior to a woman’s attempting to become pregnant. However, based on their respective half-lives, discontinuation of fingolimod for 2 months and dimethyl fumarate for 1 month seems reasonable.

The issue of the prolonged excretion of teriflunomide after its discontinuation has been addressed above. Based at least in part on experience with leflunomide, a drug that has been in use for many years for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and is metabolized to teriflunomide, the MS drug has a Category X rating, indicating that it should not be used during pregnancy. This should be discussed with the patient before she begins taking the medication, and the accelerated elimination procedure must be followed if she wants to try to become pregnant or if an unplanned pregnancy occurs.

Natalizumab, which is designated Category C, has an uncertain risk for the fetus.23 Because its immunologic effects last approximately 2 months, it is probably advisable for a woman to discontinue the drug 2 months prior to attempting conception or to stop the drug promptly if unplanned pregnancy occurs. Because natalizumab is frequently used in patients with disease that has been difficult to control, the decision to discontinue the drug prior to pregnancy must be tempered by the risk of recurrent activity after it has been stopped. Data suggest that the risk of disease activity, which peaks a few months after natalizumab cessation, is related to the degree of activity prior to initiation of the treatment.17 For more information regarding MS and pregnancy, refer to the article “Pregnancy in the Setting of Multiple Sclerosis” by Michelle Fabian, MD,25 in this issue of Continuum.

DISCONTINUATION RELATED TO ISSUES OF ADHERENCE TO MEDICATION USE

Improper adherence to an MS disease-modifying therapy is an important and commonly encountered problem. A patient’s failure to adhere to the correct regimen may have many root causes. These include tolerability (ie, side effects), emotional issues, personal schedule, and sometimes simply forgetting. While minor deviations from the recommended regimen are probably unimportant for most of the disease-modifying therapies, in some instances incomplete adherence is tantamount to discontinuation of the medication as improper usage may render the treatment ineffective. For example, dimethyl fumarate should be taken 2 times a day, best with meals. Phase 2 studies suggest that a daily dosage below the recommended dose of 240 mg 2 times a day is ineffective.26

In a thorough discussion with a patient prior to initiating therapy, the reason for treatment and expectations of its effectiveness should be reviewed and a frank and complete explanation of the drug’s side effects and strategies to alleviate them offered. Acknowledgment of how difficult it is to take medication when one cannot actually perceive a benefit (nor can one be proven) further strengthens the bond between patient and provider, increasing the likelihood of successful adherence to the regimen.

The subject of patient adherence should be addressed regularly, but always with a sympathetic and reassuring demeanor. The provider should recognize that sometimes a patient may simply not be able to follow a particular regimen and a switch to an alternative medication will be necessary. By maintaining a very supportive posture and fostering the concept of a patient-physician partnership, the physician may prevent the obviously undesirable situation of a patient’s simply not taking a medication and perhaps not informing the doctor.

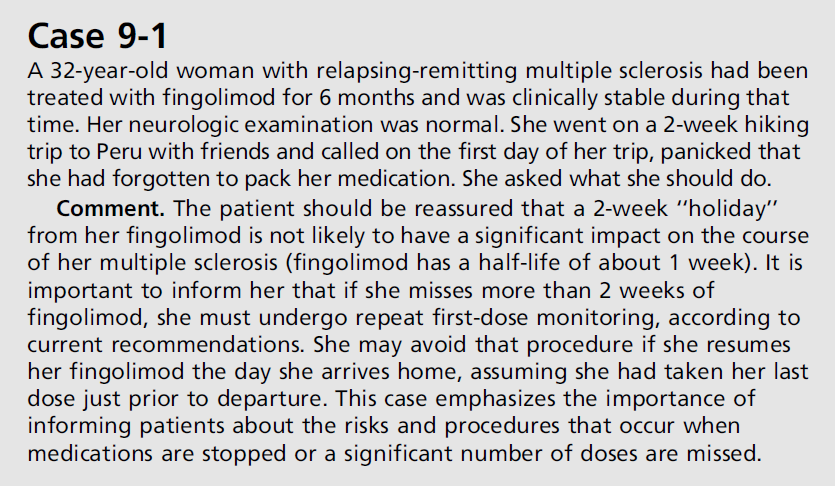

With most medications, if a break in therapy occurs, the treatment can simply be resumed according to schedule. A special procedure must be followed, however, if fingolimod is discontinued for a certain period of time. Because this drug is associated with bradycardia or other effects on atrioventricular conduction, first-dose monitoring, generally for 6 hours, is required with initiation of treatment. If the patient has been taking the medication for at least 1 month and misses more than 2 weeks of treatment, the first-dose monitoring must be repeated before resumption of regular dosing. If the patient misses 1 day or more during the first 2 weeks of therapy or more than 7 days during the third and fourth weeks of treatment, monitoring must be repeated (Case 9-1).24

DISCONTINUATION OF TREATMENT IN PATIENTS WITH SECONDARY PROGRESSIVE MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS

Unfortunately, no disease-modifying therapy has been demonstrated to be clearly effective in patients with secondary progressive MS. Very recently, however, ocrelizumab, a monoclonal antibody directed against CD20 and thereby depleting B lymphocytes, has completed a successful phase 3 trial in primary progressive MS.27 A European trial of subcutaneous interferon beta-1b in secondary progressive MS had a positive effect on disability, whereas a North American study failed to replicate this benefit.28 The likely explanation for this difference is that the European study population was skewed toward an inflammatory profile, with patients having a younger mean age, greater relapse activity, and more contrast-enhancing lesions than those in the North American trial. Although mitoxantrone has been FDA approved for use in secondary progressive MS, the Mitoxantrone in Multiple Sclerosis (MIMS) trial on which such regulatory action was based had a complicated design,29 and it seems likely that the drug works principally by preventing active inflammation. Based on the lack of efficacy of disease-modifying therapies, little justification exists at present for initiating therapy in patients with insidious secondary progressive disease. Indeed, the position that disease-modifying therapy should not be initiated for patients with progressive nonrelapsing forms of MS was emphasized as one component of the American Academy of Neurology’s contribution to the “Choosing Wisely” campaign.30 This recommendation will likely not apply to primary progressive MS if and when ocrelizumab is approved by regulatory agencies.

The inclusion of the dictum to avoid prescribing disease-modifying therapy for patients with progressive disease raised substantial protest among members of the MS professional community. This was likely, at least in part, because the reality in clinical practice is that many patients begin disease-modifying therapy when they clearly are in the relapsing-remitting stage of the illness but then transition to the secondary progressive MS phenotype. The difficult question then arises as to whether such patients should discontinue disease-modifying therapies. The interferon trials all showed a reduction in exacerbations (for patients with secondary progressive MS who continued to experience exacerbations) and new MRI activity even though they did not show a benefit in reducing confirmed disability progression. For more information on interferon beta trials in MS, refer to the article “Progressive Multiple Sclerosis” by Mary Alissa Willis, MD, and Robert J. Fox, MD, FAAN,31 in this issue of Continuum. Thus, it remains uncertain whether something is to be gained by continuing disease-modifying therapy in this situation or whether ongoing treatment is futile. For example, might a patient’s cognitive status be better preserved by continuing therapy in view of the demonstrated lessening of additional MRI disease activity? In the absence of data on such matters, the question of whether to stop or continue treatment would seem to be best handled on an individual basis and the decision made after frank discussion with the patient. The psychological impact of discontinuing therapy with the potential loss of hope by the patient also requires consideration.

SHOULD DISEASE-MODIFYING THERAPY BE DISCONTINUED IN A PATIENT WHOSE DISEASE HAS BEEN STABLE FOR A LONG TIME?

In recent years, the concept of “no evidence of disease activity” (NEDA) has gained traction, not only in the assessment of clinical trial data, but also as a treatment target. To be sure, short of the reversal of neurologic deficits from MS, NEDA is the holy grail of MS treatment. Although NEDA, even over a relatively short time frame, is still achieved in only a minority of patients irrespective of the particular medication, some people with MS do achieve remarkable stability both clinically and on imaging studies for prolonged periods of time (eg, 5 or more years). Such an absence of evident disease activity may prompt either the patient or the physician to question the continued need for disease-modifying therapy. Scant data are available to help answer the question, but a few investigators have begun to broach the subject.

In one study, Birnbaum32 reported his own personal experience in stopping disease-modifying therapy among two groups of patients whose disease had been stable for 8 to 10 years. The first group included 62 patients for whom the physician recommended discontinuation of disease-modifying therapy. In this group, only 4 of 62 worsened on MRI and only one patient had a clinical change during the variable follow-up period. The mean age in this group was 62, and of those who worsened, it was 54. The second group was composed of 10 patients who themselves initiated the discussion about stopping disease-modifying therapy. In this group, which had a mean age of 51, four patients worsened, but the age difference between those who worsened and those who did not was not significant. The author speculated that patients who are younger and themselves ask to stop disease-modifying therapy are at greater risk for disease activity.

Kister and colleagues33 reported an observational study of patients with no relapses for at least 5 years who stopped first-line (injectable) disease-modifying therapy. Data were derived from the MSBase Registry, an international prospective Internet-based registry. The authors included patients who had been relapse free for at least 5 years and had been treated continuously with disease-modifying therapy for at least 3 years prior to discontinuation; patients were followed for at least 3 years after stopping disease-modifying therapy. The cohort included 485 patients contributed by 28 sites. Patients who restarted disease-modifying therapy within 3 months of stopping were considered “switchers” and excluded from analysis.

As this was not a planned stopping trial, patients discontinued treatment for a variety of reasons, including “lack of improvement” (9%), perceived disease progression (10%), intolerance (8%), adverse event (6%), and unknown (66%). The postdiscontinuation period of observation ranged from 3 to 14.7 years, with a median of 4.85 years. During the observation period, 155 of 426 disease-modifying therapy stoppers (36.4%) had a relapse; 131 of the 391 disease-modifying therapy stoppers (33.5%) had confirmed disability progression; and 46 of 426 disease-modifying therapy stoppers (10.8%) experienced both relapse and confirmed disability progression.33 (Denominators differ because not all information was available for each patient.)

Of 182 patients discontinuing therapy (numbers updated between time of abstract submission and time of oral presentation), 77 resumed disease-modifying therapies after a median time off medication of 22 months. These patients were regarded as “restarters.” Interestingly, the disease-modifying therapy restarters had a 59% decrease in the rate of confirmed disability progression compared to those patients who remained off disease-modifying therapy. However, the relapse rates were similar in the two groups. Each increase of one point in the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) was associated with a 20% decrease in relapse rate.

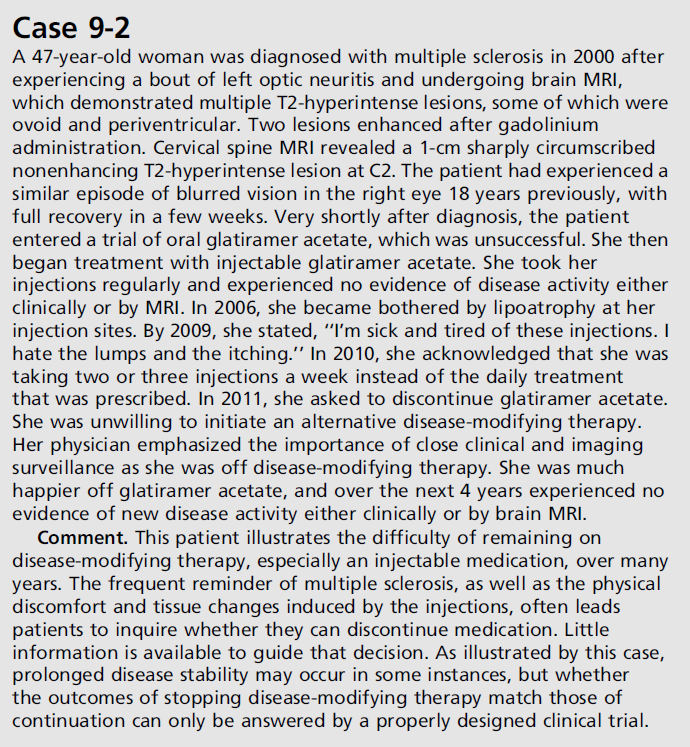

It is very difficult to draw firm conclusions from the Kister data in view of the uncontrolled observational nature of the studies. Clearly, however, patients discontinuing disease-modifying therapy had a very substantial risk of continued disease activity. The authors advocated for a randomized disease-modifying therapy discontinuation trial in stable older patients with MS. This is clearly the only way to obtain definitive information on the relative risk of discontinuing disease-modifying therapy after a period of disease stability compared to remaining on medication. The fact that 28 MSBase sites could contribute an average of fewer than seven patients each to this study, however, suggests that recruitment for such a study could be very difficult. Case 9-2 illustrates the challenges patients face in the use of disease-modifying therapies and circumstances that may warrant discontinuation of treatment with subsequent close surveillance.

In the absence of reliable data to guide decisions about discontinuing disease-modifying therapy, I do not currently introduce that possibility, even in patients whose disease has been stable for a long time, unless very unusual circumstances exist. If the patient raises the question, I will discuss frankly the available, but sparse, information and determine whether, in the particular circumstances, the patient wants to accept the risk of stopping treatment. Very recently, a prospective randomized trial of stopping versus continuing therapy in patients who are over the age of 55 and have had prolonged disease stability while continuously taking disease-modifying therapy has been funded. It is hoped that in a few years this trial may be able to provide an answer to the question of the safety of discontinuing disease-modifying therapy in stable MS.

DISCONTINUING TREATMENT IN PATIENTS MISDIAGNOSED WITH MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS

In the absence of any definitive test for MS, the diagnosis depends on an astute clinician’s judgment based on the patient’s neurologic history and examination, buttressed by the results of MRI of the brain and, frequently, the spinal cord. Additional diagnostic support can come from the results of CSF examination. It is, of course, incumbent on the physician to establish that the patient satisfies the caveat that “there be no better clinical explanation,” which has essentially been required in every proposed set of diagnostic criteria. Although a number of diagnostic criteria have been published over the years, today clinicians most often rely on the revised McDonald criteria.34 These criteria are imperfect in sensitivity and, most important, in specificity. Solomon and colleagues,35 in a survey of 122 MS specialists, found that more than 95% reported seeing at least one patient in the past year who had been diagnosed with MS for at least a year but whom they “strongly felt” did not have MS. On average, these physicians estimated that they had seen about five patients each with misdiagnosis in the preceding year. The survey respondents estimated that more than one-fourth of these patients were taking disease-modifying therapy. Although, nonspecific white matter abnormalities were most frequently felt to be the explanation for the incorrect diagnosis, a large percentage of patients actually have psychogenic (ie, functional) disorders. This population of patients is particularly challenging.

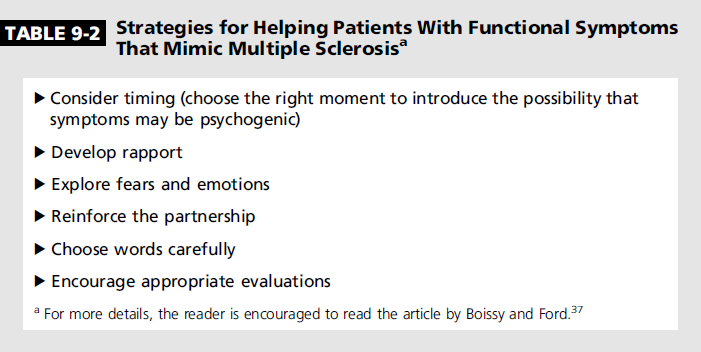

When clinicians encounter patients in whom they believe the diagnosis of MS is incorrect, they have an ethical obligation to provide their opinion about the correct explanation. For further discussion on disclosing a misdiagnosis of MS, refer to the article “Disclosing a Misdiagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis: Do No Harm?” by Andrew J. Solomon, MD, and Eran Klein, MD, PhD,36 in the August 2013 Continuum issue on MS. The situation in which a patient with an incorrect diagnosis is receiving treatment has been referred to as therapeutic mislabeling.37 In such circumstances, it is incumbent upon the physician to recommend discontinuation of disease-modifying therapy, despite the challenges of doing so, especially for the patient with a psychogenic etiology.37,38 Boissy and Ford37 offer a number of strategies for helping patients who have been misdiagnosed with MS (Table 9-2).

CONCLUSION

This article has reviewed many of the circumstances in which a disease-modifying therapy is discontinued altogether or in order to switch to an alternative medication, as well as considerations with regard to switching medications. It is critically important to be certain that the diagnosis of MS is based on solid evidence before initiating therapy and that a frank and honest discussion occur between physician and patient about the risks, benefits, and uncertainties about respective disease-modifying agents.

Maintaining a very empathic supportive relationship with the patient will help with patient adherence to a therapeutic regimen. Circumstances might arise in which the patient or the physician considers the option of discontinuing disease-modifying therapy, but both should recognize the need for much more data about the likelihood of success.

KEY POINTS

- Among the reasons a physician may advise a patient to discontinue a particular therapy are lack of efficacy, troublesome adverse events, an attempt at conception or actual pregnancy, inadequate adherence to the treatment regimen, or even recognition of erroneous diagnosis.

- Patients may discontinue disease-modifying therapies, unfortunately sometimes without informing their physicians, because of intolerable adverse events. In addition, psychological factors may interfere with a patient’s desire or ability to continue taking a particular medication or even any disease-modifying therapy at all.

- The remarkably low relapse rates among patients with multiple sclerosis in the active arms in more recent clinical trials suggest that milder disease is easier to control. This raises the question of whether all patients with multiple sclerosis need very early treatment in view of the possibility that some may experience very little disease activity even without treatment.

- In general, initiation of a new agent should be done as quickly as deemed safely possible to minimize the period of time in which a patient with multiple sclerosis is not receiving the potential benefit of disease-modifying therapy.

- Because teriflunomide leaves the body very slowly, in some circumstances, such as unexpected pregnancy, an accelerated elimination procedure must be employed.

- Patients who discontinue natalizumab are at risk for rebound disease activity, which seems to peak 3 to 4 months after the drug is stopped. Therefore, many multiple sclerosis specialists now recommend a washout period of no more than about 2 months when switching from natalizumab to another disease-modifying therapy.

- Women should generally be counseled to discontinue disease-modifying therapy when trying to become pregnant. An exception may be considered for glatiramer acetate, which has a Category B pregnancy rating.

- If a patient has been taking fingolimod for at least 1 month and misses more than 2 weeks of treatment, first-dose monitoring must be repeated before resumption of regular dosing.

- No disease-modifying therapy has been shown to be effective for secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. However, many patients begin disease-modifying therapy when they clearly are in the relapsing-remitting stage of the illness and then transition to the secondary progressive multiple sclerosis phenotype. The difficult question then arises as to whether such patients should discontinue disease-modifying therapies.

- In recent years, the concept of “no evidence of disease activity” has gained traction, not only in the assessment of clinical trial data, but also as a treatment target for multiple sclerosis. In clinical trials, only a minority of patients achieve this goal, irrespective of the drug studied.

- A randomized clinical trial is clearly the only way to obtain definitive information on the relative risk of patients’ discontinuing disease-modifying therapy after a period of disease stability compared to remaining on medication.

REFERENCES

1. Jacobs LD, Beck RW, & Simon JH, et al. Intramuscular interferon beta-1a therapy initiated during a first demyelinating event in multiple sclerosis. CHAMPS Study Group. N Engl J Med 2000;343(13):898–904.

2. Kappos L, Polman CH, & Freedman MS, et al. Treatment with interferon beta-1b delays conversion to clinically definite and McDonald MS in patients with clinically isolated syndromes. Neurology 2006;67(7):1242–1249.

3. Comi G, Martinelli V, & Rodegher M, et al. Effect of glatiramer acetate on conversion to clinically definite multiple sclerosis in patients with clinically isolated syndrome (PreCISe study): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2009;374(9700):1503–1511.

4. Comi G, De Stefano N, & Freedman MS, et al. Comparison of two dosing frequencies of subcutaneous interferon beta-1a in patients with a first clinical demyelinating event suggestive of multiple sclerosis (REFLEX): a phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 2012;11(1):33–41.

5. Miller AE, Wolinsky JS, & Kappos L, et al. Oral teriflunomide for patients with a first clinical episode suggestive of multiple sclerosis (TOPIC): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Neurol 2014;13(10):977–986.

6. Jones DE. Early relapsing multiple sclerosis. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2016:22(3 Multiple Sclerosis and Other Demyelinating Diseases):744–760.

7. Freedman MS, & Rush CA. Severe, highly active, or aggressive multiple sclerosis. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2016:22(3 Multiple Sclerosis and Other Demyelinating Diseases):761–784.

8. Kappos L, Radue EW, & O’Connor P, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of oral fingolimod in relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2010;362(5):387–401.

9. TECFIDERA (dimethyl fumarate) delayed-release capsules, for oral use. Full prescribing information. www.tecfidera.com/pdfs/full-prescribing-info.pdf. Accessed March 30, 2016.

10. Miller AE. Teriflunomide for the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2015;11(2):181–194.

11. Freedman MS, Wolinsky JS, & Wamil B, et al. Teriflunomide added to interferon-β in relapsing multiple sclerosis: a randomized phase II trial. Neurology 2012;78(23):1877–1885.

12. Freedman MS, Wolinsky JS, & Wamil B, et al. Oral teriflunomide plus glatiramer acetate in relapsing multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care 2011;13(suppl 3):P17.

13. TYSABRI (natalizumab). Prescribing information. www.tysabri.com/content/dam/commercial/multiple-sclerosis/tysabri/pat/en_us/pdfs/tysabri_prescribing_information.pdf. Accessed March 30, 2016.

14. Fox RJ, Kita M, & Cohan SL, et al. BG-12 (dimethyl fumarate): a review of mechanism of action, efficacy, and safety. Curr Med Res Opin 2014;30(2):251–262.

15. Polman CH, O’Connor PW, & Havrdova E, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of natalizumab for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2006;354(9):899–910.

16. Kappos L, Radue EW, & Comi G, et al. Switching from natalizumab to fingolimod: a randomized, placebo-controlled study in RRMS. Neurology 2015;85(1):29–39.

17. Jokubaitis VG, Li V, & Kalincik T, et al. Fingolimod after natalizumab and the risk of short-term relapse. Neurology 2014;82(14):1204–1211.

18. de Seze J, Ongagna JC, & Collongues N, et al. Reduction of the washout time between natalizumab and fingolimod. Mult Scler 2013;19(9):1248.

19. COPAXONE (glatiramer acetate injection). Prescribing information. www.copaxone.com/resources/pdfs/PrescribingInformation.pdf. Accessed March 30, 2016.

20. Houtchens MK, & Kolb CM. Multiple sclerosis and pregnancy: therapeutic considerations. J Neurol 2013;260(5):1202–1214.

21. Miller AE, Rustgi S, & Farrell C. Use of glatiramer acetate during pregnancy: offering women a choice [Abstract P733]. Mult Scler 2012;18(suppl 4):326–327.

22. BETASERON (interferon beta-1b) for injection, for subcutaneous use. Full prescribing information. labeling.bayerhealthcare.com/html/products/pi/Betaseron_PI.pdf. Accessed March 30, 2016.

23. Lu E, Wang BW, & Guimond C, et al. Disease-modifying drugs for multiple sclerosis in pregnancy: a systematic review. Neurology 2012;79(11):1130–1135.

24. GILENYA (fingolimod) capsules, for oral use. Full prescribing information. www.pharma.us.novartis.com/product/pi/pdf/gilenya.pdf. Accessed March 30, 2016.

25. Fabian M. Pregnancy in the setting of multiple sclerosis. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2016:22(3 Multiple Sclerosis and Other Demyelinating Diseases):837–850.

26. Kappos L, Gold R, & Miller DH, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral fumarate in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase IIb study. Lancet 2008;372(9648):1463–1472....

27. Montalban X, Hemmer B, & Rammohan K, et al. Efficacy and safety of ocrelizumab in primary progressive multiple sclerosis—results of the placebo-controlled, double-blind, Phase III ORATORIO study [Abstract 228]. Proceedings from the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS) 2015 Congress; October 7–10, 2015; Barcelona, Spain.

28. Kappos L, Weinshenker B, & Pozzilli C, et al. Interferon beta-1b in secondary progressive MS: a combined analysis of the two trials. Neurology 2004;63(10):1779–1787.

29. Hartung HP, Gonsette R, & König N, et al. Mitoxantrone in progressive multiple sclerosis: a placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomised, multicentre trial. Lancet 2002;360(9350):2018–2025.

30. Langer-Gould AM, Anderson WE, & Armstrong MJ, et al. The American Academy of Neurology’s top five choosing wisely recommendations. Neurology 2013;81(11):1004–1011.

31. Willis MA, & Fox RJ. Progressive multiple sclerosis. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2016;22(3 Multiple Sclerosis and Other Demyelinating Diseases):785–798.

32. Birnbaum G. Stopping disease-modifying therapy in progressive multiple sclerosis—a prospective study. Neurology 2014;82(10 suppl):P7–P207.

33. Kister I, Spelman T, & Alroughani R, et al. Are stable MS patients who stop their disease-modifying therapy (DMT) at increased risk for relapses and disability progression compared to patients who continue on DMTs? A propensity-score matched analysis of the MSBase registrants [Abstract 82]. Mult Scler J 2015;21(11 suppl):17.

34. Polman CH, Reingold SC, & Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol 2011;69(2):292–302.

35. Solomon AJ, Klein EP, & Bourdette D. “Undiagnosing” multiple sclerosis: the challenge of misdiagnosis in MS. Neurology 2012;78(24):1986–1991.

36. Solomon AJ, & Klein E. Disclosing a misdiagnosis of multiple sclerosis: do no harm? Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2013:19(4 Multiple Sclerosis):1087–1091.

37. Boissy AR, & Ford PJ. A touch of MS: therapeutic mislabeling. Neurology 2012;78(24):1981–1985.

38. Rudick RA, & Miller AE. Multiple sclerosis or multiple possibilities: the continuing problem of misdiagnosis. Neurology 2012;78(24):1904–1906.