Understanding Drivers of Employment Changes in a Multiple Sclerosis Population

Understanding Drivers of Employment Changes in a Multiple Sclerosis Population

Why is this important to me?

The physical, cognitive and emotional symptoms of MS can often have detrimental effects on a person’s ability to perform their job functions and maintain employment. Fatigue proved to be a leading symptom driving MS patients to either reduce their work hours, change to a less demanding job or leave work altogether. This article emphasizes the need for comprehensive symptom management to help patients maintain employment for long as they are able.

What did this study show?

MS patients who participated in this study reported leaving the workforce, reducing their hours or changing jobs due to worsening symptoms. Although fatigue is a leading contributor to employment changes, at least two symptoms were reported by patients which lead to their employment status. The need for comprehensive symptom management is vital to helping patients maintain employment.

Clearly, employment is linked to financial security; however, studies have shown that employment also contributes to a better quality of life and higher self-esteem. Alternatively, the loss of work or reduction in hours have permeating effects financially, emotionally and socially. Effective management of MS symptoms may help patients with productivity and enable them to work longer thus improving the overall quality of life and reducing the negative psychosocial effects associated with job loss.

How did the authors study this issue?

This study was conducted by recruiting and interviewing 27 patients with MS who reported leaving the workforce, reducing their work hours or changing jobs due to worsening MS symptoms. Participants participated in interviews with the researchers and discussed their MS symptoms and their reasoning for changing their employment situation. Of the 27 patients interviewed, the average duration of their MS diagnosis was approximately 10 years. Nearly 78% of patients reported fatigue and visual deficits as contributing factors to their employment change while others who were interviewed reported at least one cognitive symptom, such as memory loss, as a contributing factor.

What is the key take-away from this article?

Before considering a job change or leaving the work force entirely due to worsening MS symptoms it is advisable to discuss this with your health care providers. The health-care provider should be able to advise and help patients understand how worsening MS symptoms may affect their ability to adequately perform certain job functions and help prepare them for adjustments or modifications they may need to perform their routing work functions. Beginning discussions early with your health-care provider will enable you to understand and better anticipate your needs. Finally, developing a comprehensive symptom management plan with your health-care provider should help patients maintain employment and avoid the negative mental, emotional, and financial effects the loss of employment has on patients.

Original Article

Understanding Drivers of Employment Changes in a Multiple Sclerosis Population

International Journal of MS Care

Karin S. Coyne, PhD, MPH; Audra N. Boscoe, PhD; Brooke M. Currie, MPH; Amanda S. Landrian, BS; Todd L. Wandstrat, RPh, PharmD

Background: Qualitative data are lacking on decision making and factors surrounding changes in employment for patients with multiple sclerosis (MS). This study aimed to increase our understanding of the key symptoms and factors leading patients with MS to leave work or reduce employment.

Methods: Adults with MS who reported leaving the workforce, reducing work hours, or changing jobs due to MS in the past 6 months were recruited from four US clinical sites. Patients participated in semistructured interviews to discuss MS symptoms and reasons for changing employment status. All interviews were transcribed and coded for descriptive analyses.

Results: Twenty-seven adults (mean age = 46.3 years, mean duration of MS diagnosis = 10.9 years) with a range of occupations participated; most were white (81.5%) and female (70.4%). Physical symptoms (eg, fatigue, visual deficits) (77.8%) were the most common reasons for employment change; 40.7% of patients reported at least one cognitive symptom (eg, memory loss). Fatigue emerged as the most pervasive symptom and affected physical and mental aspects of patients' jobs. Most patients (85.2%) reported at least two symptoms as drivers for change. Some patients reported a significant negative impact of loss of employment on their mental status, family life, and financial stability.

Conclusions: Fatigue was the most common symptom associated with the decision to leave work or reduce employment and can lead to a worsening of other MS symptoms. Comprehensive symptom management, especially fatigue management, may help patients preserve their employment status.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a neurologic disorder commonly affecting people aged 20 to 40 years,1 which are important years for career progression and earning.2 The symptoms of MS, including neurologic disability, cognitive functioning, depression, and fatigue, have been shown to have an important effect on patients' daily activities, social relationships, and self-esteem.1,2

Growing research has been dedicated to the impact of MS on patient employment status, and studies have estimated that approximately 43% to 67% of those with MS are unemployed within 12 to 15 years of diagnosis, respectively.2–4 A recent study conducted in the United Kingdom found that rates of unemployment were as high as 75% within 10 years after diagnosis,5 and data from 18 European countries suggested that of people who leave the workforce, nearly half do so within the first 3 years after diagnosis.3Another study reported that 40% of those unemployed due to MS would like to return to work.6

Studies assessing the economic impact of MS have focused on health-care and medication costs, but fewer data are available on the indirect costs associated with loss of employment. Lifetime health-care costs for treating one patient with MS were estimated to be US$3.4 million,7 and one Australian study estimated that almost half the costs associated with MS could be attributed to loss of productivity.8 In another report, the indirect costs associated with employed patients with MS, including disability and absenteeism, were more than four times higher than those of their counterparts without MS.9

Factors prompting patients with MS to retire early include physical symptoms, ambulation problems, visual difficulties, fatigue, and emotional factors, as well as workplace environment, financial considerations, and demographic characteristics.1,3 Most studies have captured factors leading to unemployment in MS through postal questionnaires or surveys, but qualitative data assessing patients' decision-making processes are lacking.

The objective of this research was to gain an understanding of the key symptoms/factors that lead patients with MS to leave the workforce or reduce their employment hours. This information may be useful in designing strategies to assist patients in this process or reduce the loss of employment.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

In this qualitative study, adult patients with MS were recruited from four clinical sites in the United States (Dover, Delaware; Lexington, Kentucky; Englewood, Colorado; and Sunrise, Florida) to take part in a one-time, semistructured interview. Clinical site staff identified potentially eligible patients via medical record review and subsequently confirmed patient eligibility and willingness to participate via telephone or in person during a regularly scheduled appointment. No interventions or procedures were performed. The study protocol was approved by a central institutional review board, and all patients provided written informed consent before engaging in an interview.

Study Population

Patients had a clinical diagnosis of MS and must have reported applying for disability benefits, leaving the workforce, reducing work hours, or changing jobs due to MS within the past 6 months. Patients who for any reason could not provide written consent and complete an interview were excluded.

Data Collection and Analyses

Interviews were conducted in English by trained interviewers who used a semistructured, standardized discussion guide to facilitate the conversation. The guide included open-ended questions about patients' experiences with MS and factors that led them to change their employment status. Audio data collected during the interviews were transcribed and then imported into qualitative data analysis software (ATLAS.ti, version 7.0; ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany). Interviews were conducted until saturation of concepts was reached.

A content analysis approach was used to analyze the transcripts. A coding scheme was developed, and qualitative coding highlighted patient comments and emergent themes regarding employment history, the most important symptoms in deciding to make a change in employment status, and aspects of the job that became most difficult.

Patients completed a brief sociodemographic form and the Patient-Determined Disease Steps scale,10–12 a validated, patient-reported measure of disability in MS. Physicians from the sites completed a clinical form based on medical record review to capture additional information (eg, diagnosis, current MS treatments) for each patient who completed a study interview.

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the study sample, and content analysis was used to analyze qualitative data.

Results

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

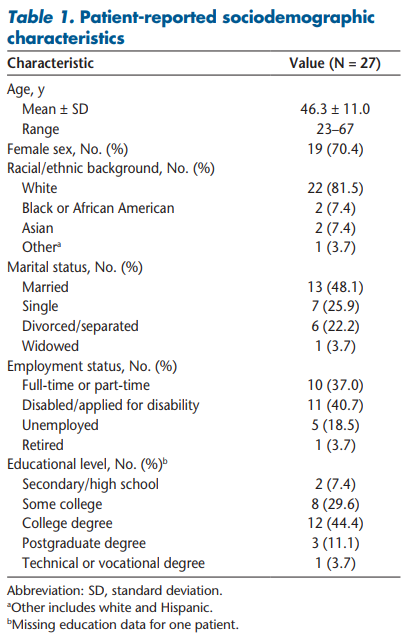

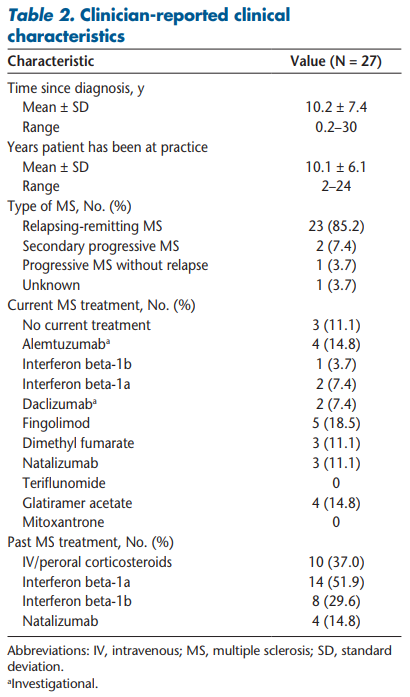

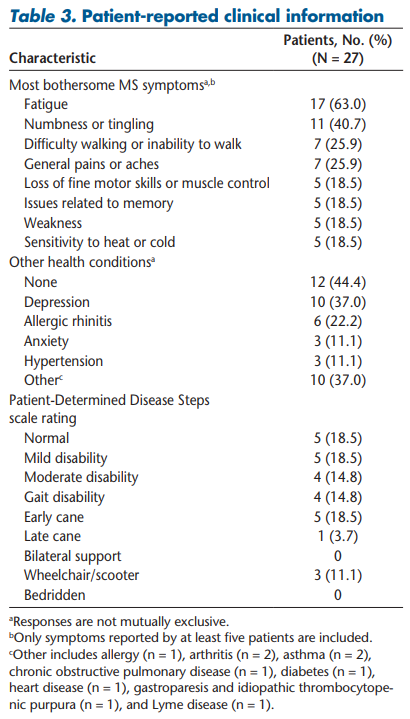

This study enrolled 27 adult patients with MS. The mean patient age was 46.3 years, with most being female (70.4%). Ten patients (37.0%) reported having either full-time or part-time employment; the remaining participants were on or applying for disability benefits or were unemployed or retired (Table 1). The mean ± SD time since MS diagnosis was 10.2 ± 7.4 years, and most patients had relapsing-remitting MS (85.2%) (Table 2). Approximately half the patients (n = 14, 51.9%) selected normal, mild, or moderate disability on the Patient-Determined Disease Steps scale (Table 3).

Qualitative Findings

General MS Experience and Symptom Descriptions

Patients were asked about their current MS symptoms and to describe which symptoms were most troubling. Seventeen patients (63.0%) cited fatigue as one of their most bothersome symptoms. Other symptoms rated as bothersome included numbness or tingling (n = 11, 40.7%), difficulty walking (n = 7, 25.9%), general aches or pain (n = 7, 25.9%), loss of muscle control or fine motor skills (n = 5, 18.5%), memory issues or forgetfulness (n = 5, 18.5%), weakness (n = 5, 18.5%), sensitivity to heat or cold (n = 5, 18.5%), vision problems or eye pain (n = 4, 14.8%), and urinary or bowel issues (n = 4, 14.8%).

Jobs/Roles Held by Study Patients and Changes Made to Employment

Patients reported a variety of occupations, including but not limited to office jobs, delivery, truck driving, waitressing, nursing, gas station attendant, and scientist. Fourteen patients (51.9%) felt that their job was both physically and cognitively demanding, eight patients (29.6%) found their job more physically demanding, and five patients (18.5%) found their job more cognitively demanding.

Eleven patients (40.7%) reported being on disability or having applied for disability benefits in the past 6 months. The remaining patients reduced their work hours to part-time (n = 6, 22.2%), stopped work entirely (early retirement or unemployed) (n = 6, 22.2%), or switched jobs due to their MS but continued working full-time (n = 3, 11.1%). One patient (3.7%) reporting working full-time recently adjusted his work schedule to mostly work from home. Of the six patients who stopped working, three (11.1%) were terminated or their position was eliminated; each suspected that they were fired or their position was eliminated as a direct result of their MS.

When asked about adjustments made on the job, patients commonly reported having to stop or limit certain tasks (n = 9, 33.3%) and having to take multiple breaks during the workday (n = 6, 22.2%). Other reported adjustments included requiring help from coworkers (n = 5, 18.5%), working from home rather than the office (n = 3, 11.1%), hiring help for roles that could no longer be done (n = 2, 7.4%), increasing the number of days or hours worked to complete tasks (n = 2, 7.4%), no longer taking on new clients (n = 1, 3.7%), and being provided with special office equipment (eg, desk, chair) (n = 1, 3.7%): “I haven't really been doing any of the filing of the charts or having to like carry large stacks of charts back to the doctors. Or having to walk around the office looking for charts. So just mostly taking the—I just mostly sit all day long” (patient H). “I'd say standing . . . I have to take, you know, breaks every now and then. I have to talk to one of the cashiers, or the head—the managers, or whatever and ask them, can I take a little break. Can I sit down for a little while? Yeah, because, uh, just standing is too much” (patient M).

When asked what aspects of the job became most difficult due to MS, patients reported paying attention, focusing, or concentrating (n = 8, 29.6%); working in the heat or cold (n = 7, 25.9%); lifting and carrying objects (n = 7, 25.9%); walking or standing (n = 7, 25.9%); and typing or writing (n = 7, 25.9%). Other aspects that became difficult included remembering to do tasks and remembering whether a task had been done (n = 6, 22.2%), driving on the job or to/from work (n = 5, 18.5%), handling stress (n = 4, 14.8%), completing tasks in a timely manner (n = 4, 14.8%), multitasking (n = 3, 11.1%), staying awake on the job (n = 3, 11.1%), and coming to work on a regular basis (n = 3, 11.1%): “I think I'm very easily distracted compared to what I used to be like. So concentrating is hard for more than a couple of hours at a time. Learning new things is difficult for me. I used to pick up things really fast and now I have to learn them over and over and write them down” (patient I). “I was getting symptoms from my MS that caused frustration in me performing my, my, my current occupation. . . . The mainly weakness on my right side of my body, which is my dominant side—my right hand in which I need that of course to do typing. So I went from—what—30 words a minute to less than 10 in typing due to the fact of my weakness. You know, I have a—it was lack of feeling at times and the fatigueness of sitting at my desk sometimes several hours, which caused tightness in my body. I was walking unstable at times when I got up from my desk” (patient N).

Interestingly, despite the variety of jobs held by study participants, the types of adjustments made and aspects of the jobs that had become the most difficult as a result of MS were relatively similar. Furthermore, the reasons and symptoms behind patients' decisions to change or adjust their employment were similar.

Key Factors and Symptoms Driving Employment Changes and Adjustments

Patients were asked to describe the key symptoms and drivers underlying the decision-making process for their recent employment changes, and often multiple symptoms factored into patients' decisions. Most patients (n = 23, 85.2%) emphasized two or more symptoms as being the drivers for employment changes or adjustments. Physical symptoms (ie, fatigue, lack of strength, and numbness/tingling) predominated, with 21 patients (77.8%) citing at least one symptom as a key driver of change.

The most common physical symptom reported was tiredness or fatigue (n = 16, 59.3%). This concept was expressed in multiple ways, including feeling “tired,” “exhausted,” and “fatigued.” A closely related symptom reported by seven patients (25.9%) was feeling weak or lacking strength or energy. Of these patients, four (14.8%) also discussed feeling fatigued or exhausted, indicating that these two symptoms may be the same or go hand in hand: “I just cut it back because I just can't do it. I get tired, I get—I can't run the equipment. Like my, you know, like trying to run a Bobcat or a backhoe or something like that. . . . I mean, I can still jog a horse or something like that, but even that . . . if it's hot out, forget about it. I'll go out and work a little while and I'm just exhausted” (patient D). “You're just tired. You—I worked fine during the day when my kids were there, and they were full days, but after the kids left it was really hard to keep moving and do the things that I needed to do to be prepared for the next day. . . . Once [the children] were gone and once it was just the paperwork and once it was just the stuff that I needed to do, especially the stuff not related to their academic success but more the paperwork ends of things. It was just—it was getting harder and harder to write. Just a working memory thing. . . . It was just like I didn't have any energy left to do that” (patient K).

Five patients (18.5%) discussed issues with muscle control and challenges with discrete tasks (eg, typing or holding objects). Other symptoms cited by patients as drivers of change included loss of balance or difficulty moving around, walking, or standing for long periods (n = 5, 18.5%); muscle stiffness or body pains (neck, back, leg, and joint) (n = 3, 11.1%); numbness or tingling (n = 3, 11.1%); headaches/migraines (n = 2, 7.4%); sensitivity to heat or cold (n = 2, 7.4%); and poor vision (n = 2, 7.4%): “I could no longer manipulate a keyboard. . . could type for about an hour and then my hands don't do what I tell them to” (patient J).

Eleven patients (40.7%) reported at least one cognitive symptom when discussing the factors that led them to make a change in employment. Memory loss or forgetfulness was the most common cognitive symptom reported (n = 7, 25.9%). Another concept that arose was a lack of mental agility or nimbleness (n = 5, 18.5%), expressed as the inability to think or process things quickly, slower reaction times, and an inability to learn new concepts or adapt to new situations quickly or easily: “Memory recall became very problematic for me. Being able to process and sync at a level that I was used to in the past. It's like my brain just—it's like having a new computer and then suddenly a few years goes by and all of the sudden it just doesn't process as fast and it takes more time to do things. . . . It's like my brain computer is just—it's gotten old, and I don't know what the upgrade for that is” (patient L).

Nine patients (33.3%) noted that their cognitive problems worsened when they felt tired or fatigued. In addition, five patients (18.5%) linked their symptoms, both physical and cognitive, to a fundamental inability to be productive, which for some ultimately led to making a change in employment status: “I'm not working enough. And one of the reasons why [my doctor] cut me back is because I'm having increased fatigue on top of everything else. My memory has gotten really bad, and I personally started having some problems with doing my job efficiently and I've always been the go-to girl and that's not the case anymore when I get too overloaded, I totally go blank. I can't think of anything” (patient G). “Just the—the ability or—or lack of ability to do the job . . . I wasn't being able to get it done in a timely fashion that I would feel good about . . . it was getting longer and longer—taking longer and longer to do it” (patient E).

Several patients also noted psychological symptoms, namely, stress and fear, which drove them to make a change in their employment. Ten patients (37.0%) reported stress as an underlying factor that eventually resulted in a decision to change or adjust their employment. Many patients talked about stress being a trigger or an underlying cause for worsening of their MS symptoms. For example, one patient commented, “that was the stress, you know . . . with the job I would end up getting fatigued from the stress . . .” (patient E). For patients who felt that their job or job environment was stressful, this was a particularly important factor in their decision making. One patient described a cycle where stress would trigger exhaustion, which rendered her unable to function properly at her job, which, in turn, increased her stress level, commenting: “So, I use, you know, my right hand's affected. So, typing an e-mail or to—updating a document was harder to do so. It took me longer so that only increased my stress and when I get stressed I get really tired and I get I don't know. I just—I just want to—I shut down. I just don't want to do anything” (patient O). “When I get into a really stressful situation, the cognitive part is a big road, totally stop and I don't know what I was talking about. [So you will just stop mid-sentence?] Just—yeah, I just—just forget what the subject was, what I was talking about, it just freezes” (patient P).

Three patients (11.1%) mentioned fear as an important reason for changing, stopping, or reducing their work. One patient (patient C), an electrician by trade, feared that her memory loss would put her customers' homes and lives in jeopardy. The same patient also discussed loss of muscle control in her hands and how that triggered a fear of heights, climbing up ladders, and dropping her tools: “I didn't want to burn somebody's house down by forgetting to do something. Or accidentally nicking a wire and not noticing it because my attention to detail is of the utmost—utmost importance . . . I was responsible for my—for my customers' lives as well as my own and their—and their personal property. . . . I think a lot of it—a lot of it was the memory loss or the forgetfulness I guess you could say. Um, the fear of the ladders, the heights, dropping my tools all the time. [And what do you attribute that to? What was the cause of dropping your tools?] Just like losing control of my hands. Sometimes it would just be like I'm holding the pen and I'm writing along and it just goes, drops right out of my hand” (patient C).

Another patient (patient P), a former martial arts instructor, discussed his fear of driving and hurting someone because of the reduced reaction time he was experiencing due to MS. A former child-care provider (patient F) discussed her fear of dropping children due to losing strength. Owing to balance issues, she also expressed fear about falling on the children: “Because I started losing strength. Like I couldn't pick the kids up, I couldn't bend down too much. It's—I just didn't feel safe messing with the kids. Because I was losing my balance a lot. So—and I didn't want to fall on one of the kids” (patient F).

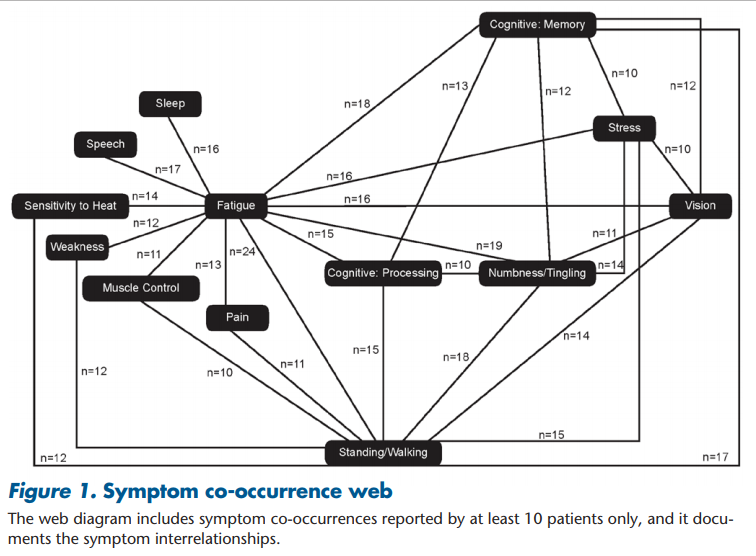

The Interconnectedness of MS Symptoms: The Fatigue Cascade Effect

Throughout the interviews, patients described how their symptoms would co-occur. Most notably, patients linked their MS symptoms to their single most bothersome symptom: fatigue. When describing their symptoms, it seemed that fatigue and general exhaustion or tiredness would trigger a cascade of other symptoms, both physical and cognitive. The downstream effects included increased clumsiness, decreased cognitive function, stuttering, shaking or muscle spasms, numbness/tingling, headaches, and blurred vision. This is captured in Figure 1, which denotes the qualitative relationships between fatigue and other symptoms and the interrelationships among the symptoms: “When your body gets to the point of that fatigue, then all these other things kick in. The fatigue then makes that numbness and tingling get worse. And so, then you feel worse on that side and, you know. And then—then my headaches, which I suffer with migraine headaches, then they get worse, and then I get floatees in my vision, and then I feel like my vision is starting—going to start getting blurry. And so, everything compounds, you know, with that terrible fatigue” (patient B). “I mean if you're tired it just makes for a longer day . . . and I found that the more tired I get, the more problems that I have with my vision” (patient A). “I would get more tired. My leg would become numb, I would have a little bit of trouble walking, and my mind would slow down. . . . I was on vacation with my family in [country name] and we were in a museum and I just got too tired . . . and my body just stopped. . . . It's like you suddenly become surrounded by concrete or something and you just can't keep going” (patient L).

Effects of MS Symptoms and Changes in Employment

Although patients were not specifically probed on the effect of their MS or employment changes on their lives, several patients spontaneously volunteered this information. Nine patients (33.3%) alluded to having lower self-worth, describing frustration or depression at no longer doing their job well, working less or not at all, or feeling like a burden to coworkers: “Well, mentally like I have experienced like some depression-type stuff with it because like I want to be a reliable employee and so it is kind of a depressive type thing that I . . . it is just upsetting to me that I'm not as reliable as I used to be, so just mentally stressed about not being that, you know, go-to–type employee” (patient H).

Five patients (18.5%) discussed the effect on their family or home life and described added financial stress due to change in their employment: “I had a big problem with being drained fast at work and then when I get home to take care of my children, I just feel that, you know, the energy is just not there to do what you want to do at home. . . . I think it has had more effect with my children than my work. . . . Just because they are active. . . . She wants to go out and play and, ah, either being tired or even once helping with schoolwork is done, I just get lost in conversation and have to backtrack a lot to, you know, to recall my information what we were sitting there talking about. But I would say the energy and my memory working probably with them is a big factor” (patient A). “It makes me sad. . . . It is also hard when you're looking at paying your bills, you know, wanting your kids to go to college and knowing that it is because you can't work that these things are difficult now. It was not the plan. . . . When your children are asking you why can't I go to such and such school or why can't—why won't you help me more financially with college and you're saying, you know, I had wanted to. The plan was that I'd be working full-time and that that would all be going toward your college education and this and that, that's hard to tell your kids” (patient I).

Discussion

Whereas steady employment is linked to financial security, better quality of life, and higher self-esteem,13 loss of work or underemployment can have widespread financial, emotional, and social impact. These consequences can be particularly pronounced in vulnerable populations, such as patients with MS.

This qualitative study explored the reasons that patients with MS decide to reduce their work hours, change positions or roles, or leave their jobs altogether. Both physical and cognitive symptoms were raised by patients, and both factored into job decisions, regardless of occupation. Fatigue was a key reason for reducing work or stopping working entirely, although it was certainly not the sole cause, as fatigue was intertwined with cognitive impairments, muscle weakness, visual difficulties, and many other symptoms. These results support findings by Simmons et al.,14 who reported that most patients with MS attribute leaving their jobs to fatigue, mobility-related issues, challenges with tasks requiring arm and hand movement, and cognitive deficits.

Patients in this study frequently spoke about symptoms worsening when their fatigue level increased, describing increased clumsiness, decreased cognitive function, blurred vision, and so on. The cascade effect of fatigue on other symptoms cannot be underestimated because this has an overarching effect on the ability of patients with MS to function at work and at home. The notion that fatigue triggers or worsens other symptoms is not novel. For example, Johnson et al.15 noted a relationship between fatigue and cognitive impairments in patients with MS, describing a cycle where fatigue led to difficulty thinking, which, in turn, led to increased fatigue. Newland et al.16 conducted a series of focus groups to explore how patients with MS describe their symptom experience. These groups yielded information on how symptoms tended to cluster, most notably fatigue, cognitive impairment, heat intolerance, and vision loss. Patients described how fatigue and heat intolerance affected their routine housework and often led to increased symptoms.

Unsolicited patient reports are consistent with previous findings by demonstrating that a loss of employment has a negative effect on patients' mental status, family life, and financial status. Flensner et al.17 found that health-related quality of life was higher in all domains (as assessed by the 36-item Short Form Health Status Survey) for people with MS who had either part-time or full-time work compared with those without work.

Similar to findings by Simmons et al.,14 one-third of patients in the present study reported being stressed by their work, and many felt that they were incapable of performing at their best. For many patients, there was fear of harming others because of the type of work they performed (eg, driving a truck, electrician, child-care provider) and their inability to safely perform their daily activities, whereas for others it was not being able to perform activities other than work, leaving them without the energy to enjoy their families. Some even seem to experience termination of employment due to their health.

Although these results have limited generalizability due to the small sample size and convenience sampling, this study provides valuable information in understanding which MS symptoms affect the decision to leave the workforce. This depth of data is useful to understanding the decision-making process and factors that patients consider when making a decision about reducing or ending their employment. The results of this study suggest that effective management of MS symptoms may help patients enhance their productivity and continue to work longer, thereby improving overall health-related quality of life and functioning and reducing the negative psychosocial effects associated with job loss or underemployment. Furthermore, the use of vocational rehabilitation services, such as education on early disclosure, effective communication with employers, workplace accommodations, and coping strategies, may also be beneficial to patients with MS in finding or regaining work or remaining in the workforce.18 Areas for future research could be identifying interventions or strategies, such as those discussed by Yorkston et al.19 to assist patients with MS in effectively managing their symptoms while at work. Identifying and using such strategies may help patients remain in the workplace longer. Additional research is also needed to assess the needs of patients and the provision of services to them in this transition period.

Acknowledgments

The Patient-Determined Disease Steps and Performance Scales were provided by the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) Registry. NARCOMS is supported in part by the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC) and the CMSC Foundation. The manuscript was reviewed by Thierry Aupérin, PhD, Steven Cavalier, MD, and Matthew Mandel, MD, of Genzyme, a Sanofi company. Editorial support was provided by Ann Marie Galioto of Fishawack Communications.

References

1. Krause I, Kern S, Horntrich A, et al. Employment status in multiple sclerosis: impact of disease-specific and non-disease-specific factors. Mult Scler. 2013;19:1792–1799.

2. Moore P, Harding KE, Clarkson H, et al. Demographic and clinical factors associated with changes in employment in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2013;19:1647–1654.

3. Messmer Uccelli M, Specchia C, Battaglia MA, et al. Factors that influence the employment status of people with multiple sclerosis: a multinational study. J Neurol. 2009;256:1989–1996.

4. Minden SL, Marder WD, Harrold LN, et al. Multiple Sclerosis: A Statistical Portrait. Cambridge, MA: ABT Associates Inc; 1993.

5. Ford DV, Jones KH, Middleton RM, et al. The feasibility of collecting information from people with multiple sclerosis for the UK MS Register via a web portal: characterising a cohort of people with MS. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:73.

6. Larocca N, Kalb R, Scheinberg L, et al. Factors associated with unemployment of patients with multiple sclerosis. J Chronic Dis. 1985;38:203–210.

7. Castelli-Haley J, Oleen-Burkey M, Lage MJ, et al. Glatiramer acetate versus interferon beta-1a for subcutaneous administration: comparison of outcomes among multiple sclerosis patients. Adv Ther. 2008;25:658–673.

8. Palmer AJ, Colman S, O’Leary B, et al. The economic impact of multiple sclerosis in Australia in 2010. Mult Scler. 2013;19:1640–1646.

9. Ivanova JI, Birnbaum HG, Samuels S, et al. The cost of disability and medically related absenteeism among employees with multiple sclerosis in the US. Pharmacoeconomics. 2009;27:681–691.

10. Hohol MJ, Orav EJ, Weiner HL. Disease steps in multiple sclerosis: a simple approach to evaluate disease progression. Neurology. 1995;45:251–255.

11. Hohol MJ, Orav EJ, Weiner HL. Disease steps in multiple sclerosis: a longitudinal study comparing disease steps and EDSS to evaluate disease progression. Mult Scler. 1999;5:349–354.

12. Marrie RA, Goldman M. Validity of performance scales for disability assessment in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2007;13:1176–1182.

13. Waddell G, Burton A. Is Work Good for Your Health and Well-Being? Norwich, UK: Department of Work and Pensions; 2006.

14. Simmons RD, Tribe KL, McDonald EA. Living with multiple sclerosis: longitudinal changes in employment and the importance of symptom management. J Neurol. 2010;257:926–936.

15. Johnson KL, Yorkston KM, Klasner ER, et al. The cost and benefits of employment: a qualitative study of experiences of persons with multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:201–209.

16. Newland PK, Thomas FP, Riley M, et al. The use of focus groups to characterize symptoms in persons with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2012;44:351–357.

17. Flensner G, Landtblom AM, Soderhamn O, et al. Work capacity and health-related quality of life among individuals with multiple sclerosis reduced by fatigue: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:224.

18. Doogan C, Playford ED. Supporting work for people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2014;20:646–650. 19. Yorkston KM, Johnson K, Klasner ER, et al. Getting the work done: a qualitative study of individuals with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2003;25:369–379.

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Coyne, Ms. Currie, and Ms. Landrian are employees of Evidera, a health outcomes research organization, and provide scientific consultation to research projects. At the time of the writing of this manuscript, Dr. Boscoe was an employee of Genzyme, a Sanofi company. Dr. Wandstrat is an employee of Genzyme, a Sanofi company.

Funding/Support: This study and the writing of the manuscript were funded in full by Genzyme, a Sanofi company.