The Effect of a Creative Art Program on Self-Esteem, Hope, Perceived Social Support, and Self-Efficacy in Individuals With Multiple Sclerosis

Why is this important to me?

Participation in the creative arts, which is naturally healing, can be beneficial to people living with chronic illnesses. Participation in a creative activity can create hope, self-esteem, and social engagement. Creating art enhances social networks, provides personal growth, and leads to a sense of confidence and optimism. Additional benefits may include a sense of achievement, control over negative thoughts and stress, and improvement in physical and cognitive skills. Social interactions and leisure activities can improve physical and mental health in people with MS and alleviate the burden of living with a chronic illness.

What is the objective of this study?

Participating in creative arts is likely to enhance your life and have a positive influence on your self-esteem, hope, social support, and confidence in functioning with and controlling your MS. Participants with MS attended four weekly creative arts sessions in which they learned watercolor, collage making, beading, and knitting. Participants were free to share their thoughts and words of encouragement during the sessions.

Participants reported improvements in their:

- Self-esteem

- Hope

- Perceived social support

- Self-efficacy to function with and control MS

What participants liked most about participating in the creative arts program was:

- Being with others

- Being creative

- Enjoyment of activity

- Learning a new skill

- Enjoyment

- Sharing feeling and experiences

- Comfortable, slow pace

- Increasing self-esteem

This program was so successful that participants decided to continue the program, even after the study was over.

How did the authors study this issue?

The authors enrolled 12 women with MS (11 white, one African-American, average age 51 years) in Missouri who participated in four weekly creative arts sessions, each 2 hours long. Participants answered questionnaires before and after attending the creative arts program.

Original Article

The Effect of a Creative Art Program on Self-Esteem, Hope, Perceived Social Support, and Self-Efficacy in Individuals With Multiple Sclerosis: A Pilot Study

Journal of Neuroscience Nursing

Cira Fraser, Michelle Keating

Abstract

Background: Creative art has been found to be beneficial to some patients with chronic illness. Little is understood about how creative art can benefit individuals living with multiple sclerosis (MS).

Objectives: The purpose of the pilot study was to determine if there was a difference in self-esteem, hope, perceived social support, and self-efficacy in individuals with MS after a 4-week creative art program.

Methods: A one-group, pretest/posttest design was used. The convenience sample of 14 individuals was recruited from MS Centers and the National MS Society. They ranged in age from 29 to 70 years (M = 51.3 years, SD = 12.5 years). Participants included 14 women. The creative art program included week 1-watercolor, week 2-collage making, week 3-beading, and week 4-knitting. Each of the four weekly sessions was facilitated by a registered nurse with expertise in MS and lasted 2 hours. Creative artists instructed participants and provided a hands-on experience for each of the creative projects. Participants were free to share thoughts, experiences, and words of support and encouragement during each session. The variables were measured before starting the creative art program and after the final session. The instruments included the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, the Herth Hope Index, the Modified Social Support Survey, the MS Self-Efficacy Scale, and a sociodemographic questionnaire. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Version 16.0 was used to analyze the data.

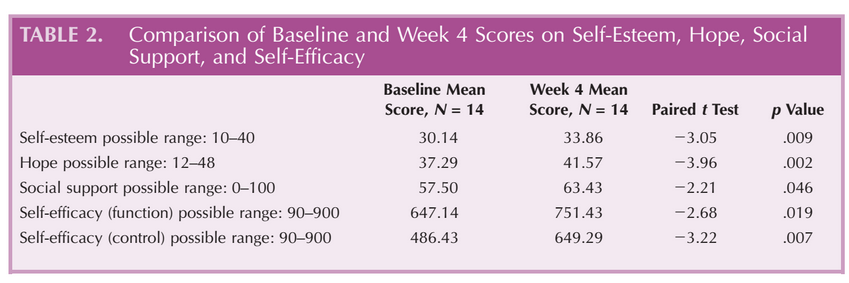

Results: There was a significant increase in all variables after the creative art program as follows: self-esteem (t = -3.05, p = 009), hope (t = -3.96, p = .002), social support (t = -2.21, p = .046), self-efficacy to function with MS (t = -2.68, p = .019), and self-efficacy to control MS (t = 3.22, p = .007). The power analysis revealed a large effect size for hope (d = 1.06), self-esteem (d = 0.82), and self-efficacy (control; d = 0.86). A medium effect size was found for self-efficacy (function; d = 0.72) and social support (d = 0.59).

Conclusions: The creative art program was found to be effective and had a positive influence on self-esteem, hope, social support, and self-efficacy to function and control MS. Creative art has the potential to enhance the lives of those living with MS and should be investigated with a larger sample of participants.

Interventions that involve creativity offer nurses a new perspective on caring for patients. When patients engage in creative activity, the process is thought to create hope and help them manage debilitating problems. The most remarkable aspect of using art for healing is the simplicity of the process. Art is naturally healing, and creative arts have been found to be successful in healthcare settings (Lane, 2005). Engagement in creative art contributes to a sense of self-esteem, hope, and social integration (Kennett, 2000). The potential health benefits of creative activity include growth in self-confidence, sense of achievement, some control of negative thoughts and feelings of stress, and the development of physical and cognitive skills (Griffiths, 2008).

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic illness that most often affects women (Compston & Wekerle, 2006). Lesions in MS may occur in the brain, spinal cord, and optic nerves, and the course of MS is highly variable (Miller, 2001). The disability of MS may include problems with fatigue, mobility, spasticity, bladder/bowel function, sexual function, cognition, hand function, vision, sensation, mood, speech and communication, swallowing, pain, and vertigo (Schwartz, Vollmer, Lee, & North American Research Consortium on Multiple Sclerosis Outcomes Study Group, 1999; Sharrack & Hughs, 1999). Persons with MS face a multitude of physical, mental, and emotional challenges on a daily basis that affect all aspects of their lives.

Several recent studies have investigated psychosocial issues in MS. Fraser and Mahoney (2010) found that, in a sample of 450 women with MS, there was a significant inverse relationship between level of disability and self-esteem (r = -.38), hope (r = -.29), self-efficacy (function; r = -.71), and self-efficacy (control; r = -.67). The investigators state that interventions to improve self-esteem, hope, and self-efficacy may be beneficial to women with MS. Strategies to enhance self-esteem include encouraging individuals with MS to join self-help groups and to participate in programs and activities. Strategies to enhance self-efficacy include reinforcing positive behaviors, providing praise, and helping individuals to attain goals. Hope interventions include fostering a sense of connectedness with others and fostering renewed spiritual self through art, music, and poetry (Fraser & Mahoney, 2010).

Social interactions and participation in leisure activities can enhance physical and mental health in MS (Khemthong, Packer, Passmore, & Dhaliwal, 2008). It is important for individuals with MS to find social activities of interest to increase social networks and interactions with other people (Fraser, Meehan, & McGurl, 2010), especially with those who have similar concerns and experiences.

Participation in creative art activities can alleviate the burden of chronic illness; however, a recent review of the literature revealed that most studies have been conducted in a hospital rather than being in community-based settings (Stuckey & Nobel, 2010). Caddy, Crawford, and Page (2012) emphasize that, in their review of the literature, there were a limited number of quantitative research studies and that most had methodological weaknesses. The investigators concluded that, despite the popularity of creative art, there is a lack of evidence regarding the relationship between participating in creative art programs and improved health. Creative and accessible solutions to improve mental health are essential components of an effective intervention program, and research is needed for socially oriented art to enhance health (Heenan, 2006).

Participation in a creative art program has the potential to enhance the lives of those living with MS. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to investigate the effect of a community-based creative art program on self-esteem, hope, perceived social support, and self-efficacy in individuals with MS using a quantitative approach.

Review of the Literature

To address the need for quantitative research to develop evidence on creative activity and health, Caddy et al. (2012) conducted a chart review of 403 patients. The participants had attended at least six sessions of a creative activity group while inpatients in a psychiatric hospital during 2004-2009. The sample included 82.4% women and 17.6% men. The mean age of participants was 47.9 years. All patients had completed standardized instruments on admission and discharge from the hospital. The instruments included the Depression and Anxiety Stress Scale, the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire, the Medical Outcomes Short Form Questionnaire, and the Health of the Nation Outcome Scale. The findings revealed that the patients improved across all measures from the time of admission to discharge from the psychiatric hospital.

Griffiths (2008) used grounded theory method to investigate the usefulness of creative activities as a medium in patients with mental health problems. Participants included both patients and occupational therapists. The eight patients who participated had attended creative activities between 6 months and 3 years. Six participants were women, and two were men. The five occupational therapist participants included three women and two men. The investigator found that, by participating in creative activities, skills can be developed and confidence can be enhanced. Engagement was found to provide a sense of purpose, a structuring of time, and a restoration of balance between leisure and work.

Reynolds and Prior (2003) conducted a phenomenological study to investigate the meaning and functions of textile art in women living with a chronic illness. The textile art included freestyle embroidery, tapestry, applique, quilting, and mixed-media work. The sample included 30 women with various chronic illnesses (cancer, chronic fatigue, severe respiratory condition MS, postpolio syndrome, and arthritis). The participants ranged in age from 29 to 72 years with most being between 48 and 65 years. Thirty were interviewed, and five provided lengthy written narratives about their experience. The interviews were unstructured and audiotaped. The data analysis revealed the following themes: (a) distracting thoughts from illness; (b) expressing grief; (c) filling an occupational void; (d) increasing choice and control; (e) increasing mindfulness/awareness; (f) enabling the revising of priorities; (g) enabling flow and spontaneity; (h) facilitating humor, joy, and positive emotions; (i) restoring a positive self-image; (j) building new social relationships; (k) contributing to others and making a difference; and (l) widening horizons, new activities, and future plans.

Reynolds and Prior (2006) also investigated the role of art making in identity maintenance/restructure in people living with cancer. An interpretive phenomenological approach was used. The participants included two women and one man. They ranged in age from 47 to 59 years. Participants all engaged in textile arts, and two also engaged in drawing and sculpture. Semistructured interviews were used, and participants were audiotaped. The transcribed interviews were analyzed and revealed. Art making was found to enhance social networks and provide continuity of identity and personal growth, a sense of competence, enhanced self-image, optimism, and confidence.

The influence of the creative arts on positive mental health and well-being was evaluated by Heenan (2006). The study was conducted in Northern Ireland. An art program was provided for 10 hours a week for 10 weeks and was facilitated by an art teacher. The sample included 12 women who were interviewed and 13 women who participated in a focus group. The participants ranged in age from 18 to 55 years. Thematic analysis of the transcribed interviews revealed that participation in the art program improved self-esteem and self-confidence, provided a safe space, and made participants feel empowered.

The experience of terminally ill patients who made and exhibited their creative arts was investigated by Kennett (2000). Participants had a weekly program of visiting artists, an art therapist, and a writer in a day center. The creative arts included pottery, painting, crafts, textiles, art therapy, and creative writing groups. The sample included six men and four women who ranged in age from 23 to 80 years. Eight participants had cancer, two had neurological conditions, and three had mental health problems. Data were collected using in-depth, semistructured, audiotaped interviews. The researcher concluded that all of the themes identified in this study focused on the four attributes of hope. The essence of the phenomenon studied was hope.

A qualitative study by Reynolds (1997) who investigated coping with chronic illness and disability through creative needlecraft was conducted. The sample included 35 women who ranged in age from 18 to 87 years. All had acquired the chronic illness or disability in adulthood. Narratives were analyzed. Needlecraft was found to provide a means of managing unstructured time and pain as well as facilitating self-esteem and reciprocal social roles.

The meaning of art making in women living with chronic fatigue syndrome was examined by Reynolds, Vivat, and Prior (2008). The sample included 10 women who provided lengthy written responses to interview questions about their experience. Art making was perceived as manageable in the context of a chronic illness. When art making was established as a leisure activity, art making increased subjective well-being by providing positive self-image, hope, increased satisfaction with daily life, and contact with the outside world. Participants felt that occupational and recreational counseling should occur earlier in the illness trajectory.

Garland, Carlson, Cook, Lansdell, and Speca (2007) compared mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) and healing through the creative arts programs on stress, spirituality, posttraumatic growth, and mood disturbance in patients with cancer. The participants were mostly women and married and had breast cancer. The MBSR group had 60 participants, and the healing-through-the-creative-arts group had 44 participants. Both programs were found to facilitate positive growth after traumatic life experiences. The MBSR was found to be more helpful than the creative arts program in reducing stress, depression, and anger and enhancing spirituality.

The effect of an art therapy program and coping resources in women with breast cancer was investigated by Oster et al. (2006). The sample included 41 women who ranged in age from 37 to 69 years who have nonmetastatic breast cancer. Participants were randomized into a study group who received art therapy (n = 20) for 1 hour per week during postoperative radiotherapy or to a control group (n = 21). The Coping Resources Inventory was used to measure coping before and 2 and 6 months after the start of radiotherapy. There was a significant increase in coping resources and social domain for the women in the art therapy program.

In summary, the experience of participating in creative arts has been investigated in a number of studies with participants who have a variety of chronic illnesses. Most often, a qualitative approach was used to generate new understanding of the outcomes after participation in creative arts. A number of important concepts have been identified using a qualitative approach. Little is understood about how creative arts can benefit individuals living with MS. The next step in knowledge development is to use reliable and valid instruments to measure the concepts in a larger study and focus on one type of chronic illness. Therefore, the research question for this study was, "Is there a difference in self-esteem, hope, perceived social support, and self-efficacy in individuals with MS after participation in a 4-week creative arts program?"

Theoretical Framework

Watson's Theory of Human Caring will guide this study. The theory "honors the unity of the whole human being, while also attending to creating a healing environment. Caring-healing modalities and nursing arts are reintegrated as essentials to ensure attention to quality of life, inner healing experiences, subjective meaning and caring practices, which affect patient outcomes" (Watson, 2005, p. 51). Caring-healing modalities may include massage, therapeutic touch, reflexology, aromatherapy, sound, music, arts, and a variety of energetic modalities (Watson, 2009). This study will focus on the art modality.

Method

Research Design

A one-group pretest/posttest design was used to determine if there was a difference in self-esteem, hope, perceived social support, and self-efficacy in individuals with MS after participation in the creative arts project. The variables were measured before participation in the creative art program and after completion of the program.

Creative Art Program

The creative art program included the following: week 1, watercolor; week 2, collage making; week 3, beading; and week 4, knitting. Each of the four weekly sessions was facilitated by a registered nurse with expertise in MS, and each session lasted 2 hours. Creative artists instructed participants and provided a hands-on experience for each of the creative projects. Participants were free to share thoughts, experiences, and words of support and encouragement during each session.

Instruments

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale is a 10-item scale that was designed to optimize ease of administration, economy of time, unidimensionality, and face validity. The scale has a 4-point Likert scale varying from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (4), resulting in a score range of 10-40 with higher scores representing higher self-esteem. The scale has shown reliability with alpha coefficients ranging from 0.77 to 0.88 (Rosenberg, 1965). Fraser, Hadjimichael, and Vollmer (2001) reported an alpha coefficient of .92 in a sample of 341 individuals with relapsing-remitting MS. Fraser, Hadjimichael, and Vollmer (2003) reported an alpha coefficient of .91 in 199 individuals with progressive forms of MS.

The Herth Hope Index is a 12-item adapted version of the Herth Hope Scale. The Herth Hope Index has a 4-point Likert scale that ranges from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (4). Scores range from 12 to 48, with higher scores representing higher hope. An alpha coefficient of .97 has been reported for this scale (Herth, 1992). Fraser et al. (2001) reported an alpha coefficient of .92 in a sample of 341 individuals with relapsing-remitting MS. Fraser et al. (2003) reported an alpha coefficient of .90 in 199 individuals with progressive forms of MS.

The Modified Social Support Survey is an 18-item multidimensional measure of perceived social support. There are four subscales (tangible support, emotional/informational support, affectionate support, and positive social interaction) as well as a total score. Each of these scores can range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater perceived support. The instrument has established reliability and validity (Ritvo et al., 1997). Reliabilities in samples of patients with MS have been reported as .99 (Osborne et al., 2006) and .93 (Williams et al., 2004).

The MS Self-Efficacy Scale (Schwartz, Coulthard-Marris, Zeng, & Retzlaff, 1996) contains 18 items that ask individuals to rate on a scale of 10-100, where 10 is very uncertain and 100 is very certain of how they will be able to perform specific behaviors. There are two subscales containing nine items each with higher scores representing a greater belief in one's ability. The function subscale (SEF) contains items that reflect an individual's sense of confidence that they can perform behaviors that allow them to engage in activities of daily living. The control subscale (SEC) reflects the individual's sense of confidence that they could control disease symptoms, reactions to disease-related limitations, and the impact of their disease on life activities. Each subscale can range in score from 90 to 900. Schwartz et al. reported an alpha reliability of .86 for the SEF and .90 for the SEC in the initial testing of the instrument. Fraser et al. (2001) reported an alpha coefficient of .90 for the SEF and .94 for the SEC in a sample of 341 individuals with relapsing-remitting MS. Fraser et al. (2003) reported an alpha coefficient of .90 on the SEF and .94 on the SEC in 199 individuals with progressive forms of MS. Fraser, Morgante, Hadjimichael, and Vollmer (2004) reported .93 on the SEF and .96 on the SEC in 108 individuals with MS initiating glatiramer acetate.

A sociodemographic questionnaire was used to gather data to describe the participants. In addition, a questionnaire administered after the week 4 session asked participants to describe what they liked most about participating in the creative art program.

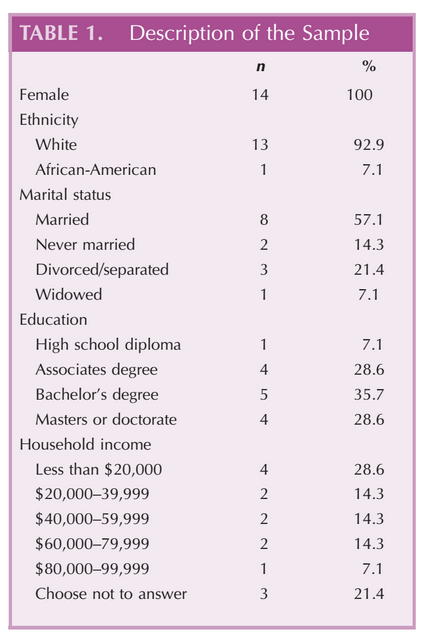

Sample

A convenience sample of 14 women with MS was recruited from several MS centers and an MS Society Chapter in Missouri. Inclusion criteria were as follows: diagnosis of MS; ability to speak, read, and understand English; and willingness to attend the four creative art sessions. Exclusion criteria were as follows: severe cognitive dysfunction and unable or unwilling to attend all of the creative art sessions. The participants ranged in age from 29 to 70 years (M = 51.3 years, SD = 12.5 years; see Table 1 for a description of the sample).

Data Collection Method

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from Monmouth University. An information letter about the study was provided, and the study was also explained to potential participants. They were free to ask questions about the study before participation. Participants were advised of the ability to withdraw from the study at any time. Those who agreed to participate completed the instruments and sociodemographic questionnaire in a quiet private area before the beginning of the creative art program. The participants were given an index card with the identification number used initially and instructed to use this number the second time the instruments were administered after completion of the 4-week program. Participants were instructed to place the completed study questionnaires into the envelope and to seal it before returning it to the investigator. Return of the completed questionnaires implied consent to participate. All envelopes were kept secure in a locked file and remained sealed until the data analysis process began.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Version 16.0. The paired t test was used to compare the premeasurement and postmeasurement of the variables. Descriptive statistics were run.

Results

There was a significant increase in all variables after the creative art program (see Table 2). The self-esteem mean score at baseline was 30.14 (SD = 6.70), with a mean of 33.86 (SD = 4.62) at week 4 after participation in the creative art program. There was a significant increase in self-esteem (t = -3.05, p = .009). The hope mean score at baseline was 37.29 (SD = 6.12), with a mean of 41.57 (SD = 4.26) at week 4 after participation in the creative art program. There was a significant increase in hope (t = -3.96, p = .002). The social support mean score was 57.50 (SD = 22.39) at baseline, with a mean of 63.43 (SD = 18.81) at week 4 after participation in the creative art program. There was a significant increase in perceived social support (t = -2.21, p = .046). The self-efficacy to function with MS mean score was 647.14 (SD = 131.76) at baseline, with a mean of 751.43 (SD = 111.90) at week 4 after participation in the creative art program. There was a significant increase in self-efficacy to function with MS (t = -2.68, p = .019). The self-efficacy to control with MS mean score was 486.43 (SD = 151.23) at baseline, with a mean of 649.29 (SD = 113.71) at week 4 after participation in the creative art program. There was a significant increase in self-efficacy to control with MS (t = 3.22, p = .007; see Table 2).

According to Cohen (1988), power analysis may be calculated after data analysis and states that a small effect size is .20, medium is .50, and large is .80. The power analysis for this study revealed a large effect size for hope (d = 1.06), self-esteem (d = 0.82), and self-efficacy (control; d = 0.86). A medium effect size was found for self-efficacy (function; d = 0.72) and social support (d = 0.59).

Participants' responses about what they liked most about participating in the creative art program were compiled, and themes were identified. In descending order of frequency, the themes were as follows: (a) being with others, (b) opportunity to be creative, (c) feeling relaxed, (d) learning a new skill, (e) enjoyment, (f) sharing feelings and experiences, (g) comfortable slow pace, and (h) building self-esteem.

Upon completion of the study, the participants wanted to continue as a group. With help from the nurse facilitator of the sessions and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, a monthly creative art group was maintained. A support partner and person with MS agreed to facilitate the monthly meetings. The group members have led new creative art projects, and several meetings were designated as "bring your own projects" that needed completion or help from other members. The group has grown to 30 members, with about 10-15 attending each meeting.

Discussion

The creative art program significantly improved participants' self-esteem, hope, perceived social support, and self-efficacy to function and control MS. Self-esteem was also identified as a finding in the qualitative research by Reynolds (1997) and Heenan (2006). Hope was also identified as a finding in the qualitative research by Reynolds et al. (2008). Perceived social support was also identified as a finding in the qualitative research by Griffiths (2008) and Reynolds and Prior (2003, 2006). Similar to the qualitative studies by Griffiths (2008), Heenan (2006), and Reynolds and Prior (2006), who used the term "confidence" when measured as self-efficacy in this study, it was found to be significantly increased after participation in the creative art program.

The findings of this study support the caring-healing modality and nursing arts as described by Watson (2005). The partnership of nursing and creative artists in providing a creative art program in a community-based setting enhanced the lives of the participants with MS.

Conclusions

The creative art program was found to be effective and had a positive influence on self-esteem, hope, social support, and self-efficacy to function and control MS. Although the sample size was small, findings were found to be significant. Future research needs to use a quantitative approach to build a solid body of knowledge in this area. Replication of this study conducted over a longer period is needed to confirm the findings. Creative art has the potential to enhance the lives of those living with MS and should be investigated with a larger sample of participants.

References

Caddy L., Crawford F., Page A. C. (2012). "Painting a path to wellness": Correlations between participating in a creative activity group and improved measured mental health outcome. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 19, 327-333.

Cohen J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Compston A., Wekerle H. (2006). The genetics of multiple sclerosis. In Compston A., Confavreux C., Lassman H., McDonald I., Miller D., Noseworthy J., (Eds.), McAlpine's multiple sclerosis (4th ed., pp. 113-181). Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, Inc.

Fraser C., Hadjimichael O., Vollmer T. (2001). Predictors of adherence to Copaxone therapy in individuals with relapsing-remitting MS. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing, 33 (5), 231-239.

Fraser C., Hadjimichael O., Vollmer T. (2003). Predictors of adherence to glatiramer acetate therapy in individuals with self-reported progressive forms of multiple sclerosis. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing, 35 (3), 163-170, 174.

Fraser C., Morgante L., Hadjimichael O., Vollmer T. (2004). Prospective study of adherence to glatiramer acetate in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing, 36 (3), 120-129.

Fraser C. J., Mahoney J. (2010). The relationship between self-efficacy, self-esteem, hope and disability in women with multiple sclerosis. In O'Mahoney D., de Burca A. (Eds.), Women and multiple sclerosis (pp. 111-123). New York, NY: Nova Biomedical Books.

Fraser C. J., Meehan D., McGurl J. (2010). A comparative study of health outcomes in women with multiple sclerosis. In O'Mahoney D., de Burca A. (Eds.), Women and multiple sclerosis (pp. 139-151). New York, NY: Nova Biomedical Books.

Garland S. N., Carlson L. E., Cook S., Lansdell L., Speca M. (2007). A non-randomized comparison of mindfulness-based stress reduction and healing arts programs for facilitating post-traumatic growth and spirituality in cancer outpatients. Supportive Care in Cancer, 15 (8), 949-961.

Griffiths S. (2008). The experience of creative activity as a treatment medium. Journal of Mental Health, 17 (1), 49-63.

Heenan D. (2006). Art as therapy: An effective way of promoting positive mental health? Disability and Society, 21 (2), 179-191.

Herth K. (1992). Abbreviated instrument to measure hope: Development and psychometric evaluation...the Herth Hope Index. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 17 (10), 1251-1259.

Kennett C. E. (2000). Participation in a creative arts project can foster hope in a hospice day centre. Palliative Medicine, 14, 419-425.

Khemthong S., Packer T. L., Passmore A.,, Dhaliwal S. S. (2008). Does social leisure contribute to physical health in multiple sclerosis related fatigue? Annual in Therapeutic Recreation, 16, 71-80.

Lane M. R. (2005). Creativity and spirituality in nursing: Implementing art in healing. Holistic Nursing Practice, 19 (3), 122-125.

Miller A. E. (2001). Clinical features. In Cook S. D. (Ed.), Handbook of multiple sclerosis (3rd ed.), pp. 213-232). New York, NY: Marcel Dekker.

Osborne T. L., Turner A. P., Williams R. M., Bowen J. D., Hatzakis M., Rodriquez A., Haselkorn J. K. (2006). Correlates of pain inferences in multiple sclerosis. Rehabilitation Psychology, 51 (2), 166-174.

Oster I., Svensk A., Magnusson E., Thyme K. E., Sjodin M., Astrom S., Lindh J (2006). Art therapy improves coping resources: A randomized, controlled study among women with breast cancer. Palliative & Supportive Care, 4 (1), 57-64.

Reynolds F. (1997). Coping with chronic illness and disability through creative needlecraft. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 60 (8), 352-356.

Reynolds F., Prior S. (2003). "A lifestyle coat-hanger": A phenomenological study of the meanings of artwork for women coping with chronic illness and disability. Disability and Rehabilitation, 25 (14), 785-794.

Reynolds F., Prior S. (2006). The role of art-making in identity maintenance: Case studies of people living with cancer. European Journal of Cancer Care, 15, 333-341. [Context Link]

Reynolds F., Vivat B., Prior S. (2008). Women's experiences of increasing subjective well-being in CFS/ME through leisure-based arts and crafts activities: A qualitative study. Disability & Rehabilitation, 30 (17), 1279-1288.

Ritvo P. G., Fischer J. S., Miller D. M., Andrews H., Paty D. W., LaRocca N. G. (1997). MSQLI: Multiple sclerosis quality of life inventory: A user's manual. New York, NY: National Multiple Sclerosis Society.

Rosenberg I. M. (1965). Society and adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Schwartz C. E., Coulthard-Marris L., Zeng Q., Retzlaff P. (1996). Measuring self-efficacy in people with multiple sclerosis: A validation study. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 77, 394-398.

Schwartz C. E., Vollmer T., Lee H.North American Research Consortium on Multiple Sclerosis Outcomes Study Group. (1999). Reliability and validity of two self-report measures of impairment and disability for MS. Neurology, 1, 63-70.

Sharrack B, Hughes R. A. C. (1999). The Guy's Neurological Disability Scale (GNDS): A new disability measure for multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis, 5, 223-233.

Stuckey H. L., Nobel J. (2010). The connection between art, healing, and public health: A review of current literature. American Journal of Public Health, 100 (2), 254-263.

Watson J. (2005). Caring science as sacred science. Philadelphia, PA: FA Davis.

Watson J. (2009). Caring science and human caring theory: Transforming personal and professional practices of nursing and health care. Journal of Health and Human Services Administration, 31 (4), 466-482.

Williams R. M., Turner A. P., Hatzakis M., Rodriquez A. A., Chu S., Bowen J. D., Haskelkorn J. K. (2004). Social support among veterans with multiple sclerosis. Rehabilitation Psychology, 49 (2), 106-113.