Calm Your Mind

| SHARE: | |||||

Original Article

Calm Your Mind

Jamie Talan

Brain & Life (formerly Neurology Now)

When Paul Boyce was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease last year at age 56, he did something unexpected. Instead of getting upset and worrying about the future, he started exercising more, eating more fruits and vegetables—and praying. His goal? To reduce the stress in his life and live more in the moment.

“I’m doing the right thing,” he says today. “I keep fighting and try to have a positive attitude.”

Like many people with neurologic conditions, Boyce is hopeful that reducing stress will help alter the course of his disease. And with good reason: The latest research reveals that stress damages the brain, and that reducing it can be highly beneficial.

STRESS EXHAUSTS THE BRAIN

Much of what we know about the effects of stress comes from studies of mice and rats, says Bruce McEwen, PhD, a scientist at The Rockefeller University in New York, who has spent most of his career studying the impact of stress on the brain.

These laboratory studies show that stress triggers chemical, cellular, and structural changes that eventually take a toll on brain function, he says. When a mouse or rat is put in a stressful situation, its hippocampus—the area of the brain that governs learning and short-term memory—gets smaller, and nerve cells shrink and lose their ability to communicate, Dr. McEwen explains. As a result, the animal has a harder time navigating its environment. With continuous exposure to stress (which occurs over a 10-day period in studies of rats), the animal’s amygdala—the part of the brain that governs anxiety and fear—increases in size.

Scientists believe that many of these same responses take place in the human brain. When it perceives a stressful threat, the hypothalamus—the region at the base of the brain that controls the “fight or flight” response—sends out signals to prepare the body either to flee from danger or fight it. These signals prompt the adrenal glands to release hormones such as adrenaline and the “stress hormone” cortisol, which then increase heart rate and blood pressure.

In the short term, these signals can help the body protect itself against harm, but over time, these responses lead to what Dr. McEwen refers to as “allostatic overload.” When the stress signal remains high, the increased heart rate and blood pressure can lead to “wear and tear on the cardiovascular system and hardening of the blood vessels. Even the immune system is called on to respond,” he says.

While acute (short-term) stress activates the immune system’s ability to defend against a pathogen or repair a wound, chronic (long-term) stress can have the opposite effect. That’s why scientists are studying whether reducing stress protects the brain and changes the course of disease—an area of research that is still evolving.

THE POWER OF POSITIVE THINKING

Can a positive attitude lessen the effects of stress? Yes, says Andrew Steptoe, PhD, and his colleagues at University College London, who have conducted several studies designed to answer that question. For example, in one study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2005, Dr. Steptoe and colleagues took blood samples from people who were asked to keep daily diaries of their positive experiences. The people who reported more positive experiences and a better mood throughout the day had the lowest levels of cortisol. Then the scientists asked these people to perform mildly stressful problem-solving tasks, after which they measured their levels of fibrinogen, a protein that is critical for blood clot formation but, in excess, indicates allostatic overload. Again, the more positive people had a lower fibrinogen response.

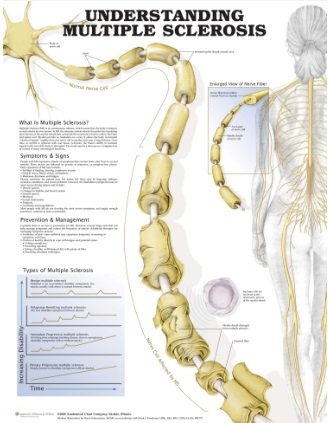

Another study tested the benefits of a stress management program for preventing new brain lesions in people with multiple sclerosis (MS). The program, developed by David C. Mohr, PhD, a professor of preventive medicine and director of the Center for Behavioral Intervention Technologies at Northwestern University, teaches people how to anticipate and reduce stressful events, how to change negative thinking about unavoidable stress, and how to practice relaxation techniques to control their physical and emotional reactions to stress.

The upshot? MS patients trained in these stress-reducing techniques had fewer lesions during the 24-week treatment phase, Dr. Mohr and colleagues reported in Neurology in 2012. In fact, of the 121 participants, almost 77 percent of those practicing stress-reduction techniques remained free of new brain lesions, compared with nearly 55 percent of those who were enrolled in the study but were put on a waiting list and had not undergone training in stress management. (The benefit disappeared once the program ended.)

“People should not interpret these data to suggest that they are, or anyone else is, in any way responsible for their exacerbations [symptom flare-ups],” Dr. Mohr says. “There is no way to say that any particular event results in disease activity. But living a life that is as fully engaged as possible is important for MS.”

MEDITATION DISARMS STRESS

Several studies have documented, through brain scans and blood work, the beneficial role meditation can play in managing stress. For example, in a 2011 study published in the journal Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, Sara Lazar, PhD, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School and an associate research scientist at Massachusetts General Hospital, reported that people who participated in an eight-week meditation program where they meditated for an average of 27 minutes each day appeared to have decreased density in the amygdala, the part of the brain related to anxiety and fear. The changes in the amygdala correlated with less self-reported stress, Dr. Lazar says. “The data indicate that meditation leads to long-term changes in brain structure that go beyond the time spent meditating each day.” (To learn more about Dr. Lazar’s research and insights on meditation, listen to her TED talk at bit.ly/TED-Sara-Lazar.)

In another study of meditation, Herbert Benson, MD, director emeritus of the Benson-Henry Institute at Massachusetts General Hospital and the endowed Mind Body Medicine professor at Harvard Medical School, compared the activity of 40,000 genes in people who meditate regularly with gene activity in a group of people who never meditated. He and colleagues collected blood before and after the program, during which participants were asked to meditate for 10 minutes twice a day. They checked the samples for white blood cells in order to measure gene expression.

They observed that in the meditation group, there was an enhanced expression of genes associated with energy metabolism, insulin secretion, and maintenance of aging cells, and a reduced expression of genes associated with inflammation and stress-related pathways, says Dr. Benson, whose work was published in the journal PLOS ONE in 2013. He credits these genomic changes to something he calls the “relaxation response,” a physical state of deep rest in which blood pressure, heart rate, and cortisol levels decrease. “The genomic changes intensified the more people practiced,” he says. (To learn more about the relaxation response, visit relaxationresponse.org/steps.)

MINDFULNESS QUIETS THE BRAIN

The practice of being more attentive, present, and engaged in each moment, also known as mindfulness, has been studied for its ability to lessen the damaging effects of stress and protect the parts of the brain that are vulnerable to Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive decline.

For instance, in a 2013 study published in the journal Neuroscience Letters, Rebecca Erwin Wells, MD, MPH, and her colleagues at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center looked at magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of 14 patients with mild cognitive impairment who participated in an eight-week mindfulness-based stress-reduction program, and compared them with brain scans from people who received standard medical care. Those who enrolled in the mindfulness program were taught to observe their thoughts and feelings in a non-judgmental way through practices like meditation and yoga.

The researchers wanted to see whether learning to manage or reduce stress would help protect the brain. Would it preserve cognitive function, lead to any changes in the size of brain structures, or have an effect on brain connectivity in areas related to learning and memory?

After comparing brain scans, both before the treatment phase and at a follow-up meeting after the treatment, the scientists found that those who participated in the mindfulness training had significantly improved connectivity in the hippocampus. Although both groups of participants showed atrophy (shrinking) of the hippocampus, those who participated in the stress-reduction program had less.

EXERCISE TAMPS DOWN CORTISOL

Many studies have shown that exercise can protect the brain against stress in a variety of conditions, including in Alzheimer’s disease. In January 2010, for example, Laura Baker, PhD, and colleagues at the University of Washington in Seattle published a study in the Archives of Neurology that looked at the effects of aerobic exercise on women with mild cognitive impairment. Participants were divided into two groups: One group exercised for one hour four times a week for six months while maintaining a heart rate of 75 to 85 percent of their maximum heart rate, while the other group followed a stretching program and kept their heart rate at or below 50 percent. At the end of the study, the women who exercised had lower levels of cortisol and were able to complete tasks, concentrate, and solve problems better than the women in the stretching group.

In another study, volunteers were asked to perform cognitive tests before and after starting a brisk walking program for six to 12 months. After the program, the walkers’ cognitive scores improved and their brains showed more activation of the prefrontal and parietal regions, areas involved in cognitive functioning.

Other studies corroborate the finding that exercise increases gray matter density in brain regions associated with high-level cognitive functioning. The research indicates, therefore, that a less-stressed brain—whether as a result of exercise or other stress-reducing techniques—can think and carry out tasks more efficiently.

That’s more than enough to keep Paul Boyce focused on his daily regimen of exercise, meditation, and time spent with family and friends. “I’m doing everything I possibly can to stay healthy,” he says

Smart Ways to Stress Less

Laughing, socializing, exercising, meditating—these are all fun, accessible ways to soften the effects of stress on your brain. Get started with one of these strategies today, and you’ll be happier and more relaxed.

1. LOOK INWARD. Spend a few quiet minutes every day meditating or practicing mindfulness; this will help ease anxiety and lower stress hormones. To learn more about meditation, watch a guided meditation with Buddhist teacher Jack Kornfield, PhD, at bit.ly/Kornfield-med. For more information about mindfulness, visit umassmed.edu/cfm or read Jon-Kabat Zinn’s Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness. For online (and sometimes free) courses on mindfulness, visit palousemindfulness.com.

2GET MOVING. Try to be physically active for at least 20 to 30 minutes each day, says Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD, director of the Mayo Clinic Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center and the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. Choose an activity you enjoy, such as walking, jogging, dancing, swimming, practicing yoga, biking, kickboxing, aerobics, or doing tai chi. Anything that gets you moving vigorously will help reduce stress—but check in with your physician before starting any exercise program.

3. BINGE ON BIG BANG THEORY RERUNS. Anything that makes you laugh makes you feel good—and some evidence even suggests that laughter can deactivate stress hormones.

4. TUNE IN TO MELLOW MUSIC. Music has a powerful effect on the brain, and can induce the release of calming hormones, thereby reducing stress, says Mark Gudesblatt, MD, a neurologist at South Shore Neurologic Associates in Patchogue, NY, and a member of the American Academy of Neurology.

5. STRENGTHEN FRIENDSHIPS. There is strong evidence that being socially active boosts cognitive ability, says Gary Small, MD, a professor of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and director of the UCLA Longevity Center. “Interacting with other people also helps us avoid feelings of loneliness, which may protect the brain, since associating with others appears to decrease the risk of Alzheimer’s disease, even if you like being alone.” For example, a UCLA study found that chronically lonely people have higher levels of inflammatory cells, which can cause brain cell damage and neurodegeneration. “The good news is that becoming and staying socially engaged may reduce your risk for dementia by as much as 60 percent,” says Dr. Small.