Sexual Function in Young Individuals With Multiple Sclerosis

Sexual Function in Young Individuals With Multiple Sclerosis: Does Disability Matter?

Why is this important to me?

Sexual function is often disregarded and frequently underdiagnosed in individuals living with MS. Studies show that the proportion of sexual dysfunction in MS is greater than that in other neurological diseases and almost 5 times greater than the general population. Further studies have found that 40% to 80% of women and 50% to 90% of men with MS experience sexual dysfunction with many reporting that it’s one of the most devastating aspects of the illness.

This study investigates the prevalence of sexual dysfunction and its relationship to sociodemographic and disease-related factors.

How did the authors study this issue?

Authors enrolled 87 people with relapsing-remitting MS in a semi-structured interview, evaluating a patient’s sexual function by investigating 3 main life areas: sociodemographic information, illness perception, and sexuality. The average age of the study population was 39 years with an average disease duration of 8 years. The semi-structured clinical interview evaluated participants on the following:

- The nature of the main sexual complaints, time of onset, and its frequency and severity

- Religious, cultural, social, sexual orientation, and lifestyle issues

- Medical data regarding MS (recent relapses, medical disorders that could cause sexual dysfunction, bladder or bowel dysfunction)

- Psychological information including problems experienced during past relationships, emotional status, and presence of psychological stressors

What did this study show?

The data gathered from this study showed that sexual dysfunction in people with MS is highly prevalent, and that approximately 70% of the study’s participants reported at least 1 symptom of sexual dysfunction and 22% reported the disorder as frequent.

The study also found that lower satisfaction with sexuality was related to the duration of the disease, and not the individual’s disability status. The study discovered that the longer a person is living with MS, the more likely they are to present with psychological and relational problems, such as lower self-esteem and other factors that relate to the decline in sexual function and lack of sexual interest.

Original Article

Sexual Function in Young Individuals With Multiple Sclerosis: Does Disability Matter?

Rocco Salvatore CalabrJ, Margherita Russo, Vincenzo Dattola, Rosaria De Luca, Antonino Leo, Jacopo Grisolaghi, Placido Bramanti, Fabrizio Quattrini

Journal of Neuroscience Nursing

Abstract

Introduction: Studies on the prevalence of sexual dysfunction (SD) in multiple sclerosis (MS) have shown that 40% to 80% of women and 50% to 90% of men have had sexual complaints. Sexual function is often disregarded during consultation with healthcare professionals, and SD is frequently underdiagnosed. The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of SD and its relationship to sociodemographic and disease-related factors, with regard to disability state, in a hospital cohort of MS patients, by using a semistructured interview.

Methods: Of 130 screened outpatients, 87 met the inclusion criteria and completed the study. The mean age of the participants was 39.3 T 8.3 years, with a disease duration of 8.3 T 5.4 years and a mean Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score of 2.04 T 0.19. Sexual function was evaluated by means of a semistructured interview, investigating a patient’s 3 main life areas: sociodemographic information, illness perception, and sexuality.

Results: Approximately 70% of the patients complained at least 1 SD (decreased libido, erectile dysfunction, premature or retarded ejaculation, painful penetration), and 22% of them reported the disorder as frequent. The disease duration was associated with lower satisfaction in sexual function, and lack of sexual interest was the most common problem having a negative correlation with EDSS.

Conclusions: Healthcare professionals involved in MS, should assess patients for SD. Further studies should be fostered to better quantify SD etiology, the degree of sexual impairment, and its impact on patients’ quality of life to ‘‘overcome’’ this problem.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common disabling condition of young adults, with many potential effects on neurological function, including sensory and autonomic function.1 Subtle neurological disturbances can directly affect sexual function at a time of life when it assumes particular importance for many people. Sexual function is, however, often not a standard part of the consultation with healthcare professionals, and sexual dysfunction (SD) is therefore frequently underdiagnosed.2

Over the last decade, the studies on the prevalence of sexual problems in MS have shown that 40% to 80% of women and 50% to 90% of men complained of SD.3,4 Actually, ejaculatory dysfunction, including premature, delayed, or retrograde ejaculation, has been empirically considered as the most frequent SD reported by men with MS (50%Y75% of cases), whereas lack of sexual interest (31.4%Y74.4%), less-intense orgasm (37%Y44.9%), and inadequate vaginal lubrication (35.7%Y48.4%) are the most frequent SD in MS women.5 Neurological disorders, with regard to MS, frequently alter sexual response by changing the process of sexual stimuli to preclude arousal, decreasing or increasing desire, curtailing genital engorgement. Patients with a neurological disease may challenge the physical ability to communicate, embrace, stimulate, engage in intercourse, and maintain urinary and bowel continence during sexual activity.2 Thus, these patients, especially if male and young, may regard their sexual loss to be its most devastating aspect of the illness. It has been proposed that MS can affect sexual function through a variety of direct and indirect mechanisms; however, the exact etiology is still a matter of debate.6,7

According to the literature, primary SD refers to direct impairment of sexual responses or feelings by neurological damage in the central nervous system, at both brain and spinal cord levels.6 Secondary SD are related to the physical changes indirectly affecting sexual responses, including fatigue, muscle tightness, spasticity or weakness, and bladder or bowel dysfunction; in addition, iatrogenic SD are considered as secondary.6 Tertiary SD relates to psychosocial issues associated with body image, emotional challenges, and cultural influences, including the commonly experienced effects of depression on sexual function and low self-esteem that indirectly affects sexual function.3,6

Several studies have identified demographic variables associated with SD, including age, number of children, education, and relationship duration; however, disease characteristics such as level of disability and duration and type of MS may play a role.8Y10

The Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) is the most widely used tool to quantify disability in MS and monitor changes in the level of disability over time.11 The relationship between SD and EDSS is still controversial, although it is commonly believed that the higher the EDSS score, the higher the SD prevalence.

This exploratory study aimed at investigating the prevalence of SD and its relationship to sociodemographic and disease-related factors, with regard to disability state, in a hospital cohort of MS patients, by using a specific semistructured interview (see Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JNN/ A122).

Methods

We enrolled 87 outpatients with relapsing-remitting (RR) MS, whose diagnosis was reached according to the McDonald’s diagnostic criteria,12 attending the MS Hub center of the IRCCS Neurolesi ‘‘Bonino-Pulejo’’ (Messina, Italy) between January and July 2016.

The study was approved by the local ethics committee (52/2015), and patients gave informed consent to enter the study.

Patients were included in the study if they had RRMS, stable first-line disease-modifying therapies in the last 6 months, disease remission for at least 60 days, no steroid therapy in the last 60 days, an EDSS score between 0 and 3.5,9 and a Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression score of less than 13 and were younger than 55 years. Patients were excluded if they had relapse of the disease in the last 2 months, preexisting major chronic illness and/or psychiatric disorders, and antidepressants or corticosteroid therapy during the last 2 months.

Sexual function was evaluated by means of a semistructured interview, a 40-item ad hoc questionnaire, elaborated by the authors, and investigating a patient’s 3 main life areas: sociodemographic information, illness perception, and sexuality. The information collected included sex, age, educational level, employment, marital status, religion, number of children, onset and disease duration, disease-modifying therapy, degree of relationship (job, family, and love satisfaction), and quality of life satisfaction (using a 5-point scale). Besides the SD itself, the questionnaire explored different aspects of a patient’s past and present sexual life, including sexual activity, masturbation, kind and frequency of sexual intercourse, sexual relationship satisfaction, and the relation between sexuality and MS.

Physical disability was assessed through the EDSS, the most common method of quantifying disability in MS and monitoring changes in the level of disability over time.11 The EDSS ranges from 0 (no disability) to 10 (death due to MS) in 0.5-unit increments that represent higher levels of disability. Scoring is based on an examination by a neurologist, which measures the impairment in 8 functional systems (pyramidal, cerebellar, brainstem, sensory, bowel and bladder function, mental functions, and others). EDSS steps 1.0 to 4.5 refer to people with MS who are able to walk without any aid, with mild to moderate disability.11

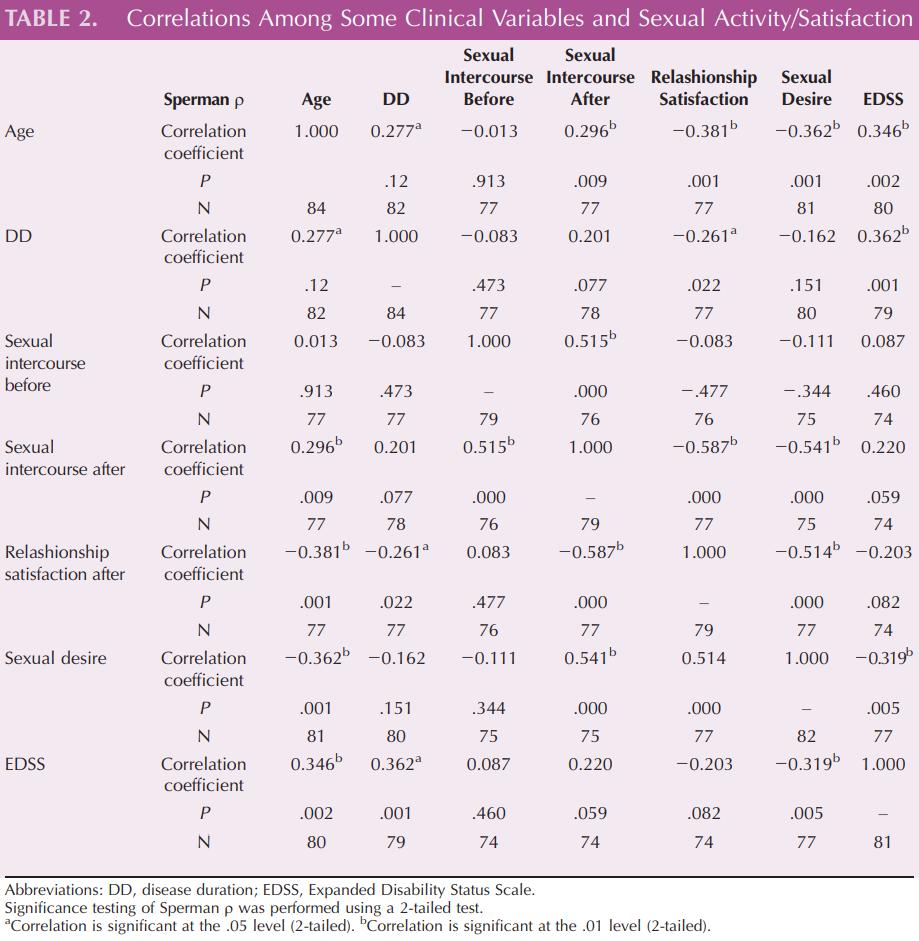

To measure the degree of association between our variables, we applied a nonparametric test (the Spearman rank correlation). Values without normal distributions were compared by Mann-Whitney U test, a nonparametric test. Only measures with P G .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

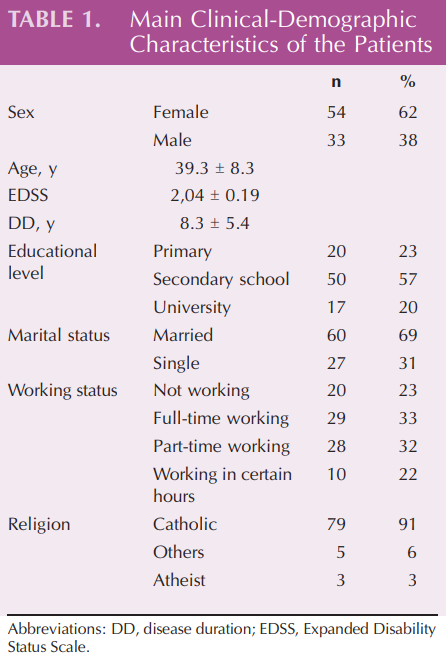

Of the 130 consecutively screened outpatients, 87 met the inclusion criteria and completed the study. Clinical and demographic characteristics are reported in Table 1.

The mean age of the participants was 39.3 T 8.3 years, with a disease duration of 8.3 T 5.4 years, an age at MS onset of 30.7 T 4.2 years, and a mean EDSS score of 2.04 T 0.19. Most of the patients had children, and more than 20% had children after the onset of the disease. Nearly all of them (90%) were Catholic, and 20% were unemployed. Sixty-one percent of the patients changed the way they viewed themselves, with a reduction of self-esteem after the diagnosis of MS.

Approximately 80% of the patients were in stable relationships, and most of them perceived their relationship as a positive experience. The frequency of sexual intercourse was significantly higher before the disease onset than after the diagnosis (P G .0001). Approximately 70% of the patients complained of at least 1 SD (in order of frequency: decreased libido, erectile dysfunction, premature or delayed ejaculation, painful penetration), and 22% of them reported the disorder as frequent. Forty percent of the patients complained of a reduced libido, which was indeed the most frequent SD. Erectile dysfunction was the most common SD in the male population (67%), whereas anorgasmia was the most frequent female SD (58%). Notably, only 23% of the patients reported masturbating.

The disease duration was associated with a lower satisfaction in sexual function, and a lack of sexual interest was the most common problem reporting a negative correlation with EDSS score (r = j0.32, P = .005), but not with disease duration (P = .1) (see Table 2).

Discussion

Our data confirmed that SD in MS is extremely common, also in young patients with mild disability. Indeed, the novelty of the study consisted in that we found such a high SD prevalence, 70%, in a sample of individuals younger than 55 years, with lower EDSS scores, suggesting the idea that disability did not have a pivotal role in causing sexual problems. Our findings are in contrast with previous studies demonstrating a positive correlation between disability (as per EDSS score) and SD.8Y10 However, the scale is sometimes criticized for its reliance on walking as the main measure of disability, as EDSS steps 5.0 to 9.5 are defined by the impairment to walking. The other items are less taken into account, although it has been demonstrated that the most robust predictors of longterm physical disability in RRMS are sphincter symptoms at onset and early disease course outcomes.13 Thus, it is hypothesized that SD may be related to other causes of disability than walking impairment.

Interactions between neural structures are essential to all phases of human sexual response and functioning, with a key role of the hypothalamic and limbic structures that act in concert with lumbar and sacral spinal centers. The correlation between SD and brain lesions is still controversial. In women, impaired sexual arousal has been associated with MS lesions in the occipital region, integrating visual information and modulating attention toward visual input, whereas impaired lubrication correlated with lesions in the left insular region, which contributes to mapping and generating visceral arousal states.14 Thus, in these cases, SD is directly linked to the neurological lesion/ dysfunction and the consequent sexual disability should be identified as primary.

Psychosocial mechanisms and the psychological variables of patients and their partners may also play a pivotal role in determining SD.6 Indeed, although a relationship between SD, pontine atrophy, and bladder dysfunction was found, a recent study highlighted the role of psychological factors in determining SD.15 More than 50% of people with MS have depressive episodes with both psychological (eg, symptoms of fatigue, stigmatization from living with a chronic illness, and struggles associated with day-by-day management) and organic (eg, location of brain lesions) components.16,17 Patients with MS who are depressed might not search for sexual intimacy, and conversely, patients with MS-related SD might experience reactive depression.16 This bidirectional association between depression and SD is supported by a recent systematic review.17 In addition, the treatment of depression itself may result in iatrogenic SD, because dopamine is known to enhance libido and sexual arousal, whereas serotonin has a clear inhibitory effect on sexuality. Thus, antidepressants with a prevalent serotoninergic action may lead to SD, with regard to anorgasmia and ejaculatory disorders.6,16 An interesting cross-sectional study has demonstrated that SD and lack of satisfaction with sexual function are associated with depression risk and fatigue,3 confirming the role of depressed mood in causing SD. This is therefore why we excluded patients with an Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score of greater than 13.

In our study, lower satisfaction with sexuality was related to the disease duration, but not with the disability status. It is possible that the longer the MS duration, the more the patients presented with psychological and relational problems, including a reduction of self-esteem, considering that approximately 60% of patients changed the way they viewed themselves after the diagnosis of MS. A 6-year follow-up study showed that age, level of physical disability, depression, and fatigue were identified as independent prognostic factors for deterioration of sexual functioning in patients with MS.18 We instead found a negative correlation between libido and physical impairment, but the patients reported by Darija et al18 had a higher mean EDSS score (5.1 T 2.1 vs 2.04 T 0.19), raising the hypothesis that other factors than physical disability may play a pivotal role in determining SD.

The high SD prevalence we found is in agreement with previous studies, although most of them have been performed in older MS patients.4,18,19 Studies on the prevalence of perceived sexual concerns in MS demonstrated that 40% to 80% of women and 50% to 90% of men have sexual complaints.6 A study performed on 2062 individuals with MS from 54 countries demonstrated that most (54.5%) reported 1 or more problems with sexual function, with lack of sexual interest (41.8% of women) and difficulty with erection (40.7% of men) as the most common.3

The proportion of SD in MS is greater than that in other neurological diseases and almost 5 times higher than in the general population.4 In line with numerous published investigations, we found lack of sexual desire as the most frequent sexual complaint.3Y6 Nevertheless, the rates of decreased libido in our MS group were within the lower range (from 31.4% to 68.6%), as demonstrated by other authors.19

Lew-Starowicz and Rola20 found that the most common complaints in a sample of men with MS were erectile dysfunction (52.9%), decreased sexual desire (26.8%), and difficulties in reaching orgasm (23.1%) or ejaculation (17.9%); moreover, the severity of SD had a clear impact on sexual quality of life, with regard to erectile function and intercourse satisfaction.

Another interesting work involving 132 women with MS showed that 87.1% of the patients reported SD, with delayed orgasm, spasticity, and concern about partner’s sexual satisfaction as the most common sexual concerns.7

Despite the recognized importance of sexual functioning problems in MS, this aspect of illness has been poorly assessed in clinical practice and therefore often remain underdiagnosed and undertreated.21 In particular, young adults with MS may see SD as the most negative feature of the disease, given the variety of disturbances of sexual function and the indirect effects on mental health, quality of life, and intimate relationships, at a time of life when sexual activity may be at a peak and seen as particularly important. Thus, an accurate diagnosis of the causes and nature of SD is necessary for an effective treatment strategy. Such treatment should include a combination of medical (pharmacological and/or surgical), educational, and counseling approaches and cognitive behavior therapy, as well as daily routine procedures and sexual activities. The ideal approach to MS patients experiencing SD should be multidisciplinary, involving different professionals, such as nurses, social workers, psychologists, and neurologists.22

The need of an accurate history collection is essential, and patients should be questioned about their sexual concerns because of the high prevalence of SD in MS and the lack of symptoms or diagnostic tools predictive of primary SD onset.16,20

This is why, in this exploratory study, we built and used a specific semistructured clinical interview, evaluating (1) the nature of the main sexual complaints, the time of onset, and its frequency and severity; (2) religious, cultural, social, and sexual orientations of the patient, besides his/her lifestyle issues; (3) medical data regarding MS (recent relapses, medical disorders potentially causing SD, bladder or bowel dysfunction); and (4) psychological information (including problems experienced during past relationships, emotional status, and presence of psychological stressors). Such an interview let us to collect much more information on SD than the commonly used scales, including ‘‘The Multiple Sclerosis Intimacy and Sexuality Questionnaire.’’

However, our questionnaire should be validated in larger-sample studies and coupled with more objective tools (such us the International Index of Erectile Function and the Female Sexual Function Index).

Conclusion

Sexual dysfunction is a highly prevalent and devastating problem in individuals affected by MS, including young patients with mild disability. Healthcare professionals (such as neurologists, nurses, and psychologists) involved in MS should assess patients about their sexual functioning, quantifying the degree of sexual impairment and its impact on patients’ quality of life, to find the best approach to ‘‘overcome’’ this often neglected problem.

References

1. Kingwell E, Marriott JJ, Jett2 N, et al. Incidence and prevalence of multiple sclerosis in Europe: a systematic review. BMC Neurol. 2013;26:13Y128.

2. CalabrJ RS. Male Sexual Dysfunction in Neurological Diseases: From Pathophysiology to Rehabilitation. New York, NY: Nova Publisher; 2011.

3. Marck CH, Jelinek PL, Weiland TJ, et al. Sexual function in multiple sclerosis and associations with demographic, disease and lifestyle characteristics: an international crosssectional study. BMC Neurol. 2016;4:16Y21.

4. Orasanu B, Frasure H, Wyman A, Mahajan ST. Sexual dysfunction in patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2013;2:117Y123.

5. Cordeau D, Courtois F. Sexual disorders in women with MS: assessment and management. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2014; 57:337Y347.

6. CalabrJ RS, De Luca R, Conti-Nibali V, Reitano S, Leo A, Bramanti P. Sexual dysfunction in male patients with multiple sclerosis: a need for counseling! Int J Neurosci. 2014; 124:547Y557.

7. Merghati-Khoei E, Qaderi K, Amini L, Korte JE. Sexual problems among women with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2013;331(1Y2):81Y85.

8. Kisic Tepavcevic D, Pekmezovic T, Dujmovic Basuroski I, Mesaros S, Drulovic J. Bladder dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: a 6-year follow-up study. Acta Neurol Belg. 2017;117(1): 83Y90. doi:10.1007/s13760-016-0741.

9. Bartnik P, Wielgov A, Kacperczyk J, et al. Sexual dysfunction in female patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Brain Behav. 2017;7:e00699.

10. Young CA, Tennant A; TONiC Study Group. Sexual functioning in multiple sclerosis: Relationships with depression, fatigue and physical function. Mult Scler. 2016. doi:10.1177/ 1352458516675749

11. Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology 1983;33:1444Y1452.

12. Polman CH, Reingold SC, Edan G, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2005 revisions to the ‘‘McDonald Criteria.’’ Ann Neurol. 2005;58:840Y846.

13. Langer-Gould A, Popat RA, Huang SM, et al. Clinical and demographic predictors of long-term disability in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:1686Y1691.

14. Winder K, Linker RA, Seifert F, et al. Neuroanatomic correlates of female sexual dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2016;80:490Y498.

15. Zorzon M, Zivadinov R, Locatelli L. Correlation of sexual dysfunction and brain magnetic resonance imaging in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2003;9:108Y110.

16. CalabrJ RS, Russo M. Sexual dysfunction and depression in individuals with multiple sclerosis: is there a link? Innov Clin Neurosci. 2015;12:11Y12.

17. Atlantis E, Sullivan T. Bidirectional association between depression and sexual dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sex Med. 2012;9:1497Y1507.

18. Darija KT, Tatjana P, Goran T, et al. Sexual dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: a 6-year follow-up study. J Neurol Sci. 2015;358:317Y323.

19. Marck CH, Neate SL, Taylor KL, Weiland TJ, Jelinek GA. Prevalence of comorbidities, overweight and obesity in an international sample of people with multiple sclerosis and associations with modifiable lifestyle factors. PLoS One. 2016;5:11.

20. Lew-Starowicz M, Rola R. Sexual dysfunctions and sexual quality of life in men with multiple sclerosis. J Sex Med. 2014;11:1294Y1301.

21. Hatzichristou D, Kirana PS, Banner L, et al. Diagnosing sexual dysfunction in men and women: sexual history taking and the role of symptom scales and questionnaires. J Sex Med. 2016;13:1166Y1182.

22. Delaney KE, Donovan J. Multiple sclerosis and sexual dysfunction: a need for further education and interdisciplinary care. NeuroRehabilitation. 2017;41:317Y329.