Multiple Sclerosis and Pregnancy

Why is this important to me?

MS affects many women at an age when they are most likely to want to have a baby. You may have questions about how MS and its treatments affect pregnancy and how pregnancy and breastfeeding affect MS.

What is the objective of this study?

Before the 1960s, women with MS were generally advised to avoid pregnancy. However, current thinking is that patients with MS can usually have a successful pregnancy.

Irregular menstrual cycles occur at about the same rate in women with MS as the general population. Hormone levels may be different in women with MS, but the clinical significance of this is unclear.

In general, women with MS who are planning a pregnancy are recommended to discontinue their disease-modifying therapy one menstrual cycle before trying to conceive. Some medications for MS have been shown to be safer than others during pregnancy. Although human pregnancy studies have not been conducted for MS drugs, the FDA issues recommendations about the safety of drugs during pregnancy. Glatiramer acetate, interferon-beta, fingolimod, and natalizumab may pose some risk for the fetus, but in some cases the benefits of their use outweighs the risks. Mitoxantrone and terflunomide are generally considered to be harmful to the fetus and should not be taken during pregnancy. Be sure to talk to your healthcare provider about any medications you are taking if you are planning a pregnancy or discover that you are pregnant so that you can work with them to weigh the risks and benefits of continuing, changing, or stopping your MS therapy.

Pregnancy is a state of immune tolerance, and the blood of pregnant women contains anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive molecules. Consistent with this, the rate of MS relapses during pregnancy is lower than before pregnancy. However, the relapse rate goes up after birth. The blood of pregnant women contains anti-inflammatory properties. However, studies of the impact of MS on relapse rates are inconclusive, and more studies are required to understand better the effects of pregnancy on long-term MS outcomes.

Pregnant women with MS can utilize epidural and other types of anesthesia with no increase in the risk of MS relapse after delivery or in disability progression. Pregnant women with MS can have a vaginal or Cesarean delivery as determined by their obstetrical needs.

MS does not increase the risk of birth defects in your baby.

Studies of the impact of breastfeeding on relapses and disability are, at this time, conflicting and inconclusive.

In summary, if you have MS and are pregnant or planning to have a baby, be sure to talk to your healthcare provider so that you can make the best choices for your baby and your MS treatment goals.

How did the author study this issue?

The author reviewed studies that investigated the relationship between MS and various aspects of pregnancy.

Original Article

Multiple Sclerosis and Pregnancy

Clincal Obstetrics and Gynecology

Maria Houtchens, MD, MMSI

Abstract

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic neurological illness affecting adults at the time when they are most likely to consider starting a family. It is known that the risk of MS relapse declines during pregnancy but increases in the first 3 to 6 months postpartum. It is also known that this risk is not affected by delivery method, anesthesia type, or parity. Unanswered questions remain, including long-term pregnancy effects on MS outcomes, effects of lactation on postpartum relapses, or the best management strategies of MS patients through reproductive cycle. This review provides information and guidelines for counseling patients with MS desiring motherhood.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic autoimmune neurologic illness affecting adults at the time in their lives when they are most likely to consider starting a family. It is a complex inflammatory and demyelinating disorder of the central nervous system resulting in initially intermittent, and later, often, progressive neurological impairment. MS produces characteristic lesions that may affect the brain, the spinal cord, and the optic nerve. It is the leading cause of neurological disability in young adults. The loss of the myelin sheath results in decreased axonal transmission and axonal disruption. Clinical symptoms may include weakness and numbness in the extremities, decreased balance, poor vision, and trouble with bladder and bowel control. Women are affected more frequently than men (70% vs. 30%, respectively), and MS can impact a woman’s reproductive years. Approximate MS prevalence is 500,000 patients in the United States, and an increasing trend for women had been reported.

Although onset of MS in pregnancy is uncommon, large numbers of female patients express desire to become pregnant after receiving MS diagnosis. Therefore, issues of contraception, conception, pregnancy, childbirth, and child rearing become critically important in the overall management strategies of MS patients and have been of great interest to neurologists and reproductive specialists. Disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) and other medications are widely used by women of childbearing potential. Understanding the reciprocal effects of pregnancy and MS, the benefits and risks of currently available MS therapies, and the psychological impact of motherhood on a patient with chronic neurological illness are all important considerations for both patients and providers involved in their care.

The opinion on the safety of pregnancy for women with MS has dramatically changed through the years. For many decades, pregnancy has been regarded as having deleterious effect on the course of MS. This view was largely based on isolated instances of relapses occurring in pregnancy or the puerperium. A review at the turn of the 20th century described small series of patients in which pregnancy had an apparent adverse influence on the onset of the disease, to the point that “therapeutic abortion should have been considered” when the disease began during pregnancy or when it was associated with an exacerbation. Therefore, before 1960s, patients with MS were actively discouraged from becoming pregnant. Studies published subsequent to 1950s failed to demonstrate any definite adverse effect of pregnancy on the course of the disease. In 2012, National MS Society stated that “In general, pregnancy does not appear to affect the long-term clinical course of MS. Women who have MS and wish to have a family can usually do so successfully with the assistance of their neurologist and obstetrician.”

Pregnancy is a state of immune tolerance; it is recognized to induce changes in maternal immune system, including immunosuppression on a local level and a heightened state of immunocompetence on a global level. The serum of pregnant women contains high levels of immunologically active substances with known anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressant effects in humans and in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis MS models in animals. Combined effects of these factors reduce the numbers of circulating lymphocytes and macrophages, inhibit production of nitric oxide, and decrease the rate of synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines.

Some effects of pregnancy on the course of the MS are well accepted, whereas others require further study.

Pregnancy is Associated With a Decrease in MS Relapses During the Second and Third Trimesters and is Followed by an Equivalent Increase in Relapse Rate in the First 3 to 6 Months of Postpartum. There is no Persistent Long-term Effect on Increase in a Relapse Rate

Several retrospective studies reported an overall increase in relapse rate during the postpartum period and a lower relapse rate during pregnancy. Pregnancy in multiple sclerosis was the first prospective study of 254 women (269 pregnancies). Subjects were followed for 2 years after delivery.8,9 In the cohort, prepregnancy rate of 0.7 relapses per year decreased to 0.2 per year in the third trimester. The relapse rate increased to 1.2 per year in the first 3 months postpartum. However, 72% of women did not experience any relapses during the study period. An increased relapse rate in the year before pregnancy, an increased relapse rate during pregnancy, and a higher EDSS score at the beginning of pregnancy correlated significantly with occurrence of a postpartum relapse. Pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum relapse rate did not have an effect on disability progression. Epidural anesthesia and breastfeeding were not predictive of a subsequent relapse or of disability progression.

There Are no Contraindications to Cesarean Section or Vaginal Delivery in MS Patients

Decision regarding the mode of delivery is usually based on obstetrical rather than neurological factors. A rare issue in a severely disabled patient with pelvic floor weakness due to MS may be the inability to push in the second stage of labor. Under these circumstances, cesarean section or vacuum extraction may be considered.

All Forms of Obstetrical Anesthesia Are Safe for Pregnant MS Patients

There are anecdotal cases of increase in relapse rate after spinal anesthesia in pregnant MS patients. One older study reported that women who received epidural anesthesia of bupivacaine >0.25% had a higher incidence of postpartum relapses. However, multiple subsequent prospective studies failed to demonstrate any evidence of an increase in postpartum relapse rate or disability progression, based on the mode of obstetrical anesthesia.

Long-term Effects of the Number of Pregnancies and the Risk of Developing MS, and the Risk of Disability Progression in Women With MS, Are Not Well Understood

Overall, there does not seem to be a compelling evidence of adverse effects of pregnancy on MS progression. In fact, 1 population-based prospective study showed a decrease in disability.12 This 5-year study compared the rate of progression in disability between childless women, women who had onset of MS after childbirth, and women who had onset before or during their pregnancy. The rates of disability increased most rapidly in nulliparous women.

Another study retrospectively examined childbirth’s effects on disability progression in 330 women with MS. Women who gave birth after MS onset reached EDSS scores of 6 significantly later in the disease course than those who did not (median time to progression, 13-15 vs. 22-23 y). The timing of pregnancies relative to the onset of MS was not associated with disability. Disability was also evaluated in patients with pregnancies before the onset of MS as compared with patients whose pregnancies occurred after the diagnosis. No overall difference was found between these 2 patient groups. The data also failed to demonstrate that pregnancy negatively affects the long-term outcome of MS.

A recently published Ausimmune Study examined an association between past pregnancy, offspring number, and first clinical demyelination risk. This Australian case-controlled study examined the 282 women with an incident diagnosis of first demyelinating event (FDE) and 542 matched controls. Higher parity was associated with a reduced risk of FDE. There was a 49% reduction in the risk of FDE diagnosis for each further birth, and the association persisted after controlling for genetic and environmental risk modifiers [HLA DRB1-15, EBV exposure, serum 25(OH)D levels].

A large recent Canadian study looked at clinical and term pregnancy data from 2105 female MS patients and determined that delay in reaching the Expanded Disability Status Score of 6 by patients having children after MS diagnosis could be explained by the age of MS onset rather than the number of term pregnancies. These results may suggest that pregnancy does not have an independent effect in reaching advanced disability levels.

Effect of Pregnancy on the Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) in MS Patients

An increase in new or enlarging MRI lesions postpartum was reported in several studies. Even though the overall number of subjects has been small, over half of MS women had MRI changes in the last trimester of pregnancy and within 4 to 12 weeks of postpartum. In another study of 60 patients with radiologically isolated syndrome, followed for up to 7 years, those women who became pregnant were more likely to develop new MRI disease activity, suggesting that pregnancy may activate disease in presymptomatic MS patients.

Effect of MS on the Risk of Fetal Malformations, Duration of Pregnancy, or Pregnancy Outcomes Has Been Conflicting

No significant adverse effects on fetal or maternal pregnancy outcomes have been reported. MS does not increase the risk of fetal malformations. However, there may be a higher rate of operative deliveries and induced labor as well as greater numbers of neonates with low birth weight or being small for gestational age. Kelly and colleagues evaluated obstetric outcomes in women with MS, epilepsy, or pregestational diabetes mellitus and in healthy controls. On average, women with MS were older than women in the other 3 groups. MS patients had 30% higher risk for cesarean delivery and 70% higher rate of intrauterine growth restriction than did healthy women. There were no long-term adverse pediatric outcomes.

It is Generally Recommended to Discontinue the Use of Disease-modifying Drugs (DMDs) for All Pregnant MS Patients

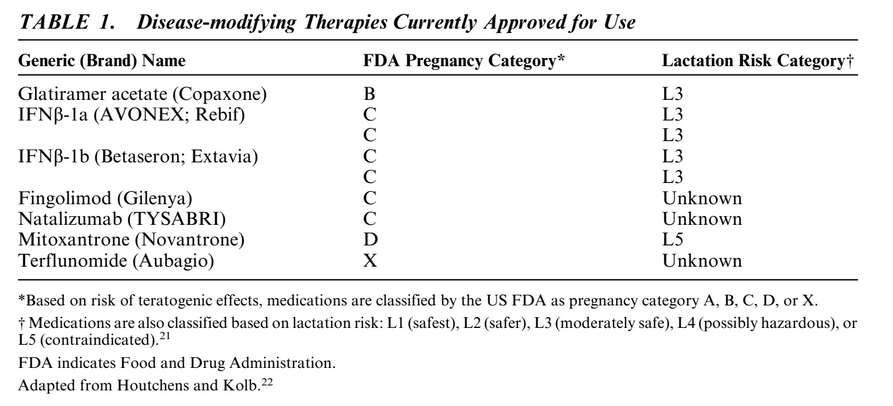

Eight therapies are currently approved for treatment of MS: glatiramer acetate (GA), subcutaneous interferon [beta] (IFN[beta])-1a, intramuscular IFN[beta]-1a, subcutaneous IFN[beta]-1b, fingolimod, natalizumab, terflunomide, and mitoxantrone. Table 1 details the general characteristics and approved indications for these agents. Adequate, well-controlled prospective human pregnancy studies have not been completed to date for any of these therapies. There are variable data on safety of immunomodulatory and immunosuppressant therapies used in MS (Table 1).

GA is the only DMT with a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) pregnancy category B rating. This rating is based on the results of studies in rats and rabbits that show no adverse effects on offspring development at up to 36 times the therapeutic human dose. However, because well-controlled studies of pregnant women are lacking and animal reproduction studies are not always predictive of human response, the US prescribing information for GA states that this DMT should be used during pregnancy only if clearly needed. Published postmarketing reports from open-label observations and data from pregnancy registries seem to confirm preclinical studies and suggest that GA is not associated with a teratogenic risk, or, with a higher risk of miscarriage.

In primates, administration of up to 100 times the recommended weekly human dose of IFN[beta] was not associated with teratogenicity or other adverse effects on fetal development. Despite these data, IFN[beta] drugs have been given a pregnancy category C rating by the FDA on the basis of experimental primate studies showing abortifacient activity at 2 to 100 times the corresponding human dose.

In contrast to these preclinical findings, postmarketing data from several large pregnancy registry studies suggest that IFN[beta]-1a is not associated with an increase in the rate of spontaneous abortions in humans.

Fingolimod has been given a pregnancy category C rating by the FDA based on experimental rat and rabbit studies showing developmental toxicity, including teratogenicity (in rats) and embryolethality, when fingolimod was administered to pregnant animals. Receptors affected by fingolimod (sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors) are known to be involved in vascular formation during embryogenesis. Pharmacokinetic studies suggest that the drug may take approximately 2 months to be completely eliminated from the body. As there is a potential risk of fetal harm with fingolimod, it is recommended that women of childbearing potential should use effective contraception to avoid pregnancy during and for 2 months after stopping fingolimod treatment.

Natalizumab has been given a pregnancy category C rating by the FDA based on results of a guinea pig study showing a small reduction in pup survival when the drug was administered at 7 times the human dose. In addition, a primate study showed hematologic effects on the fetus when the drug was administered at 2.3 times the human dose. Although there are no well-controlled studies of natalizumab efficacy and safety in pregnant women, results of the prospective natalizumab pregnancy registry, currently including nearly 300 patients, suggest that treatment has no apparent adverse effect on pregnancy outcomes in humans.

Mitoxantrone is a cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agent approved for the treatment of secondary progressive MS. It intercalates with DNA and inhibits topoisomerase II, and it is considered a potential human teratogen. It has been given a pregnancy category D rating by the FDA. Adverse effects on the developing fetus were observed with structurally related agents. In preclinical models, administration of mitoxantrone to rats during the organogenesis period of pregnancy was associated with fetal growth retardation at doses of 0.01 times the recommended human dose on an mg/m2 basis.

The newly approved DMD terflunomide has been designated pregnancy category X. It acts by inhibiting pyrimidine synthesis and it has a very long half-life, on average >2 weeks. Teriflunomide is teratogenic and is contraindicated to pregnant women and women of childbearing age who are not using a reliable method of contraception. The labeling recommends that all women of childbearing potential who become pregnant discontinue teriflunomide immediately follow an accelerated elimination protocol using cholestyramine or activated charcoal.

Intravenous steroids are used in MS for treatment of acute relapses. Their use is not associated with fetal malformations and is probably safe in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. They should be reserved for treatment of serious exacerbations of the disease because they cross placental barrier and may cause transient neonatal leukocytosis (dexamethasone) or immunosuppression (methylprednisolone).

Effects of Assistive Reproductive Technologies on the Course of MS Are Not Well Known

A recently published study looked at 32 women with MS who underwent in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatments for infertility. A significant increase in relapse rate after IVF attempts was associated with the use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, and with the failed IVF attempts.

There is a Small Increase in MS Risk in First-degree Relatives

The lifetime risk for developing MS is 0.1% to 0.2%. Having the first-degree relative with MS increases this risk to 2% to 4%. The risk of maternal and paternal transmissions are likely similar, although some controversy is present on this subject.24 Approximately 15% of all MS patients have 1 close or distant relative with MS, but the majority of patients have no family history. If both parents have MS, the risk in offspring increased to 20%.25

Menstrual Cycle and MS

Irregular menstrual cycles have been reported in 14% to 15% of MS patients, a figure comparable to that of the general population. In 1 study, despite normal menstrual patterns and fertility, MS patients had statistically significant increases in mean serum prolactin, follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, total and free testosterone, 5-[alpha]-dihydrotestosterone, and [delta]-4-androstenedione levels, and decreased levels of estrone sulfate. These results are of uncertain clinical significance but may have implications on fertility in MS patients. The effect of the menstrual cycle on MS symptoms is variable. Women who worsen during their menstrual cycles have shown improvement with oral contraceptives or estrogen treatment. Oral contraceptive use does not have adverse effects on the incidence, overall prognosis, or the degree of disability of MS.

Lactation in Patients With MS

Previous studies of breastfeeding and postpartum relapses have found either a protective effect or no association with postpartum relapses or disability increase. The studies that found no effect, did not distinguish between exclusive and nonexclusive breastfeeding. Exclusive breastfeeding was associated with a protective effect on a decrease in relapse rate postpartum in recent publications. Prolonged lactation-related amenorrhea resulted in a 4-fold decreased of postpartum relapses and with a decrease in TNF-[alpha]-producing CD4 cells. If a patient desires to breastfeed, but their MS is not in full control postpartum, intravenous immunoglobulin may be particularly useful during breastfeeding to reduce postpartum relapse rate without causing adverse effects to the infant. This is well substantiated in the published literature.

Summary

MS female patients of childbearing age should receive counseling on family planning and conception planning from their healthcare team. Expedited referrals to fertility specialists should be provided to those patients who are not able to spontaneously conceive, to prevent extended periods of time off MS treatments. Patients should be advised to stop their DMDs 1 menstrual cycle before attempting conception. Women who wish to continue taking a DMT during pregnancy should avoid mitoxantrone, fingolimod, and terflunomide. Of the other agents, patients and their doctors should weigh the risks and benefits of continuing DMDs based on published data. Women should be advised to discontinue their DMT treatment if they unexpectedly become pregnant. This particularly applies to mitoxantrone, fingolimod, and terflunomide. Women taking GA, IFN[beta], and natalizumab should be reassured that data from pregnancy registries suggest that none of these compounds are teratogenic. If there is documented exposure to high-risk approved or off-label compounds in the first trimester, the patient should be expeditiously referred to a high-risk maternal fetal medicine specialist for ongoing pregnancy follow-up. Intravenous prednisone, prednisolone, and methylprednisolone are moderately safe in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy for the treatment of serious acute exacerbations. Patients may be reassured that pregnancy is associated with a lower rate of MS exacerbations in the second and third trimesters. There is an increase in relapse rate in the 3 to 6 months of postpartum. Methods of obstetrical anesthesia and mode of delivery are not related to the likelihood of postpartum relapse. If possible, all immunomodulating agents should be avoided during breastfeeding. Exclusive breastfeeding for the first 2 months of postpartum may be independently associated with decreased postpregnancy relapse rate, although additional studies are needed to support these preliminary findings.

Author Information

Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Brookline, Massachusetts

The author declares that there is nothing to disclose.

Correspondence: Maria Houtchens, MD, MMSI, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Brookline, MA. E-mail: [email protected]

References

1. Trapp BD, Peterson J, Ransohoff RM, et al.. Axonal transaction in the lesions of multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:278–285.

2. Noonan CW, Kathman SJ, White MC. Prevalence estimates for MS in the United States and evidence of an increasing trend for women. Neurology. 2002;58:136–138. Ovid Full Text Bibliographic Links

3. Schapira K, Poskanzer DC, Newell DJ. Marriage, pregnancy and multiple sclerosis. Brain. 1966;89:419–428. Bibliographic Links

4. Beck. Multiple Sklerose Schwangerschaft und Geburt Deutsche Ztschr f Neroenheilk [Multiple Sclerosis, Pregnancy and Labor] 1913 xlvi 127 By Zentralbl f d ges Gynak u Geburtsh sd Grenzgeb

5. National Multiple Sclerosis Society. January 2013. Available at: http://www.nationalmssociety.org/living-with-multiple-sclerosis/healthy-living/pregnancy/index.aspx. Accessed January 8, 2013

6. Damek DM, Shuster EA. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72:977–989. Ovid Full Text Bibliographic Links

7. Drew PD, Chavis JA. Female sex steroids: effects upon microglial cell activation. J Neuroimmunol. 2000;111:77–85. Bibliographic Links

8. Vukusic S, Hutchinson M, Hours M, et al.. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis (the PRIMS study): clinical predictors of post-partum relapse. Brain. 2004;127:1353–1360. Ovid Full Text Bibliographic Links

9. Confavreux C, Hutchinson M, Hours MM, et al.. Rate of pregnancy-related relapse in multiple sclerosis. Pregnancy in Multiple Sclerosis Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:285–291 30

10. Bader AM, Hunt CO, Datta S, et al.. Anesthesia for the obstetric patient with multiple sclerosis. J Clin Anesth. 1988;1:21–24. Bibliographic Links

11. Perlas A, Chan VW. Neuraxial anesthesia and multiple sclerosis. Can J Anaesth. 2005;52:454–458. Bibliographic Links

12. Runmarker B, Andersen O. Pregnancy is associated with a lower risk of onset and a better prognosis in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 1995;118:253–261. Bibliographic Links

13. Coyle PK. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis. Neurol Clin. 2012;30:877–888. Bibliographic Links

14. D’hooghe MB, Haentjens P, Nagels G, et al.. Menarche, oral contraceptives, pregnancy and progression of disability in relapsing onset and progressive onset multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2012;259:855–861. Ovid Full Text Bibliographic Links

15. Ponsonby AL, Lucas RM, van der Mei IA, et al.. Offspring number, pregnancy, and risk of a first clinical demyelinating event: the autoimmune study. Neurology. 2012;78:967–974 49

16. Ramagopalan S, Yee I, Byrnes J, et al.. Term pregnancies and the clinical characteristics of multiple sclerosis: a population based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 2012;83:793–795. Ovid Full Text Bibliographic Links

17. Paavilainen T, Kurki T, Färkkilä M, et al.. Lower brain diffusivity in postpartum period compared to late pregnancy: results from a prospective imaging study of multiple sclerosis patients. Neuroradiology. 2012;54:823–828. Bibliographic Links

18. Lebrun C, Le Page E, Kantarci O, et al.. Impact of pregnancy on conversion to clinically isolated syndrome in a radiologically isolated syndrome cohort. Mult Scler. 2012;18:1297–1302. Bibliographic Links

19. Dahl J, Myhr KM, Daltveit AK, et al.. Pregnancy, delivery and birth outcome in women with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2005;65:1961–1963. Ovid Full Text Bibliographic Links

20. Kelly VM, Nelson LM, Chakravarty EF. Obstetric outcomes in women with multiple sclerosis and epilepsy. Neurology. 2009;73:1831–1836. Ovid Full Text Bibliographic Links

21. Hale TW. Maternal medications during breastfeeding. Clin Ob Gyn. 2004;3:696–711.

22. Houtchens MK, Kolb C.. Multiple sclerosis and pregnancy. Therapeutic considerations. J Neurol. 2012 [Epub ahead of print]

23. Foucher ML, Vukusic YS, Confavreux C, et al.. Increased risk of multiple sclerosis relapse after in vitro fertilisation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 2012;83:796–802.

24. Herrera BM, Ramagopalan SV, Orton S, et al.. Parental transmission of MS in a population-based Canadian cohort. Neurology. 2007;69:1208–1212 64

25. Sadovnick AD, Baird PA, Ward RH. Multiple sclerosis updated risk for relatives. Am J Med Genet. 1988;29:533–541. Bibliographic Links

26. Grinsted L, Heltberg A, Hagen C, et al.. Serum sex hormone and gonadotropin concentrations in pre-menopausal women with multiple sclerosis. J Intern Med. 1989;226:241–244. Bibliographic Links

27. Langer-Gould A, Huang SM, Gupta R, et al.. Exclusive breastfeeding and the risk of postpartum relapses in women with multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:958–963. Ovid Full Text Bibliographic Links

28. Langer-Gould A, Gupta R, Huang S, et al.. Interferon-gamma-producing t cells, pregnancy, and postpartum relapses of multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:51–57. Ovid Full Text Bibliographic Links