What People Are Talking About: Medical Marijuana

Why is this important to me?

The use of medical marijuana is increasing and may help people with certain conditions or diseases. With Multiple Sclerosis, you may experience many symptoms including spasticity and pain. With all the talk in the news about medical marijuana, you may have wondered if this may help with your symptoms.

What is the objective of this study?

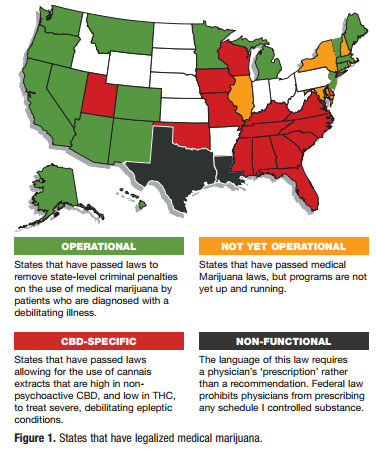

- In this summary, we will use the term "medical marijuana" to mean marijuana used for purposes allowed by certain US states and Canada. At the time of this study, medical marijuana was legal in 23 states and the District of Columbia. Although marijuana is illegal to grow, sell, or buy for recreational purposes, it is allowed for medical use in some circumstances. Patients who wish to use medical marijuana must obtain an identification card issued by the state, be evaluated by a healthcare provider for its use, and receive the marijuana from a state-approved dispensary.

- Marijuana contains two main compounds with biological effects.

- THC (tetrahydrocannabinol) is a psychoactive compound that acts in the brain to produce feelings of euphoria, pain relief, and increased appetite.

- CBD (cannabidiol) is not psychoactive and acts in the brain to protect nerve cells and reduce inflammation.

- The ratio of THC to CBD is important for therapeutic effects. Formulations with a 1:1 ratio of THC:TBD appear to be the most beneficial and have the least harmful side effects. However, marijuana plants vary in this ratio, and labeling of marijuana formulations is often inaccurate, making standardized dosing difficult.

- Medical marijuana can be taken orally or by smoking.

- Two oral forms of synthetic THC are FDA approved:

- Dronabinal (Brand name, Marinol)

- Nabilone (Brand name, Cesamet)

- These forms of THC appear to be slower acting and produce milder effects than inhaled marijuana.

- Another formulation called nabiximol (Brand name, Sativex) is an oral mucosal spray and is approved for use in Europe but not in the US or Canada.

- Medical marijuana may be useful for relieving:

- Pain

- Muscle spasms

- Possible adverse effects of medical marijuana include:

- Low blood pressure

- Sedation

- Nausea

- Disorientation

- Dizziness

- Impaired motor skills

- Reduced cognitive ability

- Hallucinations

- Memory problems

- Anxiety

- Paranoia

- Withdrawal

- Research into the safety and effectiveness of medical marijuana is limited, and therefore, many physicians question its legitimate use and are reluctant to prescribe it. Studies are currently underway to investigate the use of medical marijuana in MS. More research, quality control and regulations for standardized dosing are still needed and you should discuss this with your healthcare provider.

How did the author study this issue?

The author reviewed current data and attitudes about the use of medical marijuana to treat a variety of conditions including MS.

| SHARE: | |||||

Original Article

Medical Marijuana

Home Healthcare Now

Teri Capriotti, DO, MSN, CRNP

The use of medicinal marijuana is increasing. Marijuana has been shown to have therapeutic effects in certain patients, but further research is needed regarding the safety and efficacy of marijuana as a medical treatment for various conditions. A growing body of research validates the use of marijuana for a variety of healthcare problems, but there are many issues surrounding the use of this substance. This article discusses the use of medical marijuana and provides implications for home care clinicians.

Marijuana is the most commonly used illicit drug in the United States according to the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health Report. It is also the third most popular recreational drug in the United States, behind alcohol and tobacco. In 2013, there were 19.8 million users—about 7.5% of people aged 12 or older—up from 14.5 million (5.8%) in 2007 (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2015; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2015). Use of marijuana is increasing and home healthcare clinicians need to be aware of the issues surrounding its use as a medicinal and recreational drug.

Medical marijuana is legal in 23 states and the District of Columbia, but it is still considered a federal offense to grow, sell, or purchase marijuana. The permitted use of marijuana varies state to state. In a growing number of states, marijuana is allowed for medicinal use but is illegal for recreational use. However, there are many states where any type of use is still illegal (Figure 1). Because of its therapeutic potential, medicinal marijuana is recommended by an increasing number of clinicians for various disorders. However, because of the federal criminalization of marijuana, evidencebased research into its effectiveness has been hindered, and many clinicians still question its scientific legitimacy (Aggarwal et al., 2009; Bostwick, 2012).

Marijuana, also known as Cannabis sativa, has been used since ancient times for therapeutic, spiritual, and recreational purposes. Clinicians in the United States prescribed marijuana for many different conditions until it was declared illegal and removed from the United States Pharmacopeia in 1942. The Controlled Substance Act of 1970 placed marijuana in the Schedule I category as a substance with high potential for abuse, the same as illicit street drugs (Aggarwal et al., 2009).

Marijuana Constituents

The two primary compounds that contribute to marijuana’s therapeutic value are tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD). Natural marijuana plants contain 5% to 15% THC, the most active ingredient. Different types of marijuana plants vary in the THC-to-CBD ratio, which makes dosage standardization difficult. Studies show that a THC-to-CBD ratio of 1:1 has the most therapeutic potential and least amount of adverse effects. However, there is widespread inaccuracy in the labeling of THC content of cannabis products, which is problematic when prescribing a dosage (Bostwick, 2012; Vandrey et al., 2015). THC, the primary psychoactive component of marijuana, binds to cannabinoid receptors in the brain and produces feelings of euphoria, altered sense of time, analgesia, increased appetite, and impaired memory. CBD is a nonpsychoactive compound that is a serotonin receptor agonist with anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects (Bostwick; Whiting et al., 2015).

Pharmacokinetics

The pharmacokinetics of THC vary depending on the route of administration. Medical marijuana can be administered by inhalation or orally. Inhaled THC causes maximum plasma concentration after 15 to 30 minutes, with a duration of 2 to 3 hours. Following oral ingestion of the plant, effects begin in 30 to 90 minutes and can last up to 12 hours (Bostwick, 2012; Whiting et al., 2015). The duration of marijuana’s effects depends on dosage; however, it is unclear how to deliver a specific dose of marijuana by smoking or oral plant consumption. Marijuana products differ in their concentration of THC and labels are commonly inaccurate. Anecdotally, patients report that the inhalation route is the most effective mode of delivery (Vandrey et al., 2015; Whiting et al.).

The FDA has approved two oral forms of synthetic THC: dronabinol (Marinol) and nabilone (Cesamet). Patients report that these agents are slow acting and less effective than inhaled forms of marijuana. Nabiximol (Sativex), an oral mucosal spray, has been approved for medicinal use in Europe only (Bostwick, 2012; Whiting et al., 2015).

FDA Schedule Categorization

As a Schedule I drug, the marijuana plant is categorized as a substance with high potential for abuse and dependence (Drug Enforcement Agency, 2015). This categorization as Schedule I is widely debated—many clinicians and experts in the field argue that use of marijuana is not addictive. Other clinicians and experts describe marijuana as a “gateway” drug that can pave the way for use of stronger drugs such as cocaine or heroin, particularly in adolescents (Bostwick, 2012; Degenhardt et al., 2010; Ginzler et al., 2003). The FDA categorizes the synthetic forms of marijuana, nabilone as a Schedule II drug, and dronabinol as a Schedule III drug, which indicate that these have less abuse potential and do not usually lead to dependence (Bostwick).

Therapeutic Uses of Marijuana

Studies show the most common conditions for which medical marijuana is being prescribed include HIV/AIDS wasting syndrome, cancer chemotherapy, and pain. The American College of Physicians (ACP) recommends medicinal marijuana for the following therapeutic uses (ACP Position Paper, 2008; Borgelt et al.; 2013; Bostwick, 2012).

- As an appetite stimulant in HIV/AIDS wasting syndrome

- As an antiemetic agent in chemotherapy treatment of cancer

- As an analgesic for cancer pain

- As an agent in reducing intraocular pressure in glaucoma (however, there is no increased benefit compared with available established drugs)

- As an antispasmodic agent in neuromuscular disorders such as multiple sclerosis and spinal cord injury

Medical marijuana has been shown to be particularly effective in pain management. Marijuana potentiates analgesic effects when used with narcotics, thereby diminishing the dosage of opioids needed for pain relief (Greenwell, 2012; Hill, 2015). Currently, studies are being conducted to evaluate the use of medical marijuana in rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis and spinal cord injury, Crohn disease, endometriosis, epilepsy, and fibromyalgia. Marijuana’s anxiety-reducing effects are being studied for use in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (Borgelt et al., 2013; Hill; Whiting et al., 2015)

Adverse Effects and Safety Issues

It is important for the home healthcare clinician to be aware of the possible adverse effects of marijuana use, which include hypotension, sedation, nausea, disorientation, dizziness, decreased reaction time, reduced motor skills, diminished cognitive ability, hallucinations, and impaired memory. Some patients report increased anxiety or paranoia after using inhaled marijuana. Studies have shown increased symptoms of psychosis in patients with schizophrenia after smoking marijuana (Moss et al., 2015; Pacek et al., 2013; Peters et al., 2012). It is also common for marijuana users to suffer from nicotine dependence and alcohol abuse. The long-term effects of inhaled marijuana on the respiratory system are similar to those associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Inhaled marijuana is believed to contain as much as three times the amount of carcinogens as cigarettes (Peters et al.).

Marijuana, also known as Cannabis sativa, has been used since ancient times for therapeutic, spiritual, and recreational purposes.

Cannabis use disorder and cannabis withdrawal syndrome are recognized psychiatric disorders. Studies suggest that there is a withdrawal syndrome when chronic marijuana use is abruptly discontinued. The symptoms of withdrawal syndrome include restlessness, agitation, and insomnia (Farmer et al., 2015; Gorelick et al., 2012).

Implications for Healthcare Providers

There is widespread agreement among healthcare providers as to the need for further studies and medical education regarding medicinal marijuana. Many providers feel unprepared to prescribe marijuana and want formalized training regarding its medical uses. Kondrad (2013) reported that most surveyed physicians are receiving information about medicinal marijuana from the media or from other clinicians.

Before a patient can receive marijuana for medicinal use, he or she must apply for a state-issued identification card. The patient needs to be evaluated for the need for medical marijuana by a healthcare provider. The application is reviewed by a public-health board that assesses the patient’s eligibility for the treatment. Once a patient is approved to receive the medication, he or she receives the marijuana from a state-approved dispensary and is eligible to receive the maximum amount permitted per month (Lynne-Landsman et al., 2013; State of New Jersey Department of Health, 2015). In New Jersey, for example, clinicians and patients must be registered with the state health department’s Medical Marijuana Program (MMP) for the patient to obtain the treatment. Patients can only apply to register after a clinician registered with the program has completed a formal statement advocating the MMP for the patient (State of New Jersey Department of Health). The patient must have a diagnosis of one of the debilitating conditions the MMP has approved for treatment with medical marijuana. Once approved, the clinician can prescribe up to 2 oz of marijuana per month, to be dispensed in one-eighth or one-quarter-ounce packages (State of New Jersey Department of Health).

Anecdotally, some believe that medicinal marijuana is being predominantly used by those who are not ill but want legal protection for recreational use of the drug. This is a widely debated issue. Clinicians and patients need to be aware that growing, selling, buying, or producing marijuana in any way is a federal offense (Indianapolis Business Journal, 2015). The ACP strongly encourages more research and funding for rigorous scientific evaluation of the potential therapeutic benefits of medical marijuana. In addition, the ACP urges evidence-based review of marijuana as a Schedule I drug to determine if it should be reclassified. The ACP strongly promotes protection from criminal or civil penalties for patients who are legally prescribed medical marijuana under state law; the association also supports exemption from criminal prosecution, civil liability, or professional sanctioning of clinicians who prescribe the drug in accordance with state laws.

Conclusion

Although growing, possessing, and smoking marijuana remain illegal at the federal level, individual states have been legalizing it for medical use since 1986. The drug has been shown to have therapeutic effects in certain patients, but further research is needed regarding the safety and efficacy of marijuana as a medical treatment for various conditions. There also needs to be more standardization of the constituents and quality control of medicinal cannabis products.

Teri Capriotti, DO, MSN, CRNP, is a Clinical Associate Professor, College of Nursing, Villanova University, Villanova, Pennsylvania. The author declares no conflicts of interest. Address for correspondence: Teri Capriotti, DO, MSN, CRNP, Clinical Associate Professor, Villanova University, 800 Lancaster Avenue, Villanova, PA 19085 ([email protected]). DOI:10.1097/NHH.0000000000000325

REFERENCES

Aggarwal, S. K., Carter, G. T., Sullivan, M. D., Zumbrunnen, C., Morrill, R., & Mayer, J. D. (2009). Medicinal use of cannabis in the United States: Historical perspectives, current trends, and future directions. Journal of Opioid Management, 5(3), 153-168.

American College of Physicians Position Paper. (2008). Supporting research into the medical use of marijuana. Retrieved from http://www.acponline.org/acp_policy/policies/supporting_ medmarijuana_2008.pdf

Borgelt, L. M., Franson, K. L., Nussbaum, A. M., & Wang, G. S. (2013). The pharmacologic and clinical effects of medical cannabis. Pharmacotherapy, 33(2), 195-209.

Bostwick, J. M. (2012). Blurred boundaries: The therapeutics and politics of medical marijuana. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 87(2), 172-186. Retrieved from www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3538401/

Degenhardt, L., Dierker, L., Chiu, W. T., Medina-Mora, M. E., Neumark, Y., Sampson, N., …, Kessler, R. C. (2010). Evaluating the drug use “gateway” theory using cross-national data: Consistency and associations of the order of initiation of drug use among participants in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 108(1-2), 84-97.

Drug Enforcement Agency. (2015, August 10). Drug schedules. Retrieved from http://www.dea.gov/druginfo/ds.shtml

Farmer, R. F., Kosty, D. B., Seeley, J. R., Duncan, S. C., Lynskey, M. T., Rohde, P., …, Lewinsohn, P. M. (2015). Natural course of cannabis use disorders. Psychological Medicine, 45(1), 63-72.

Ginzler, J. A., Cochran, B. N., Domenech-Rodríguez, M., Cauce, A. M., & Whitbeck, L. B. (2003). Sequential progression of substance use among homeless youth: An empirical investigation of the gateway theory. Substance Use & Misuse, 38(3-6), 725-758.

Gorelick, D. A., Levin, K. H., Copersino, M. L., Heishman, S. J., Liu, F., Boggs, D. L., & Kelly, D. L. (2012). Diagnostic criteria for cannabis withdrawal syndrome. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 123(1-3), 141-147. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.11.007

Greenwell, G. T. (2012). Medical marijuana use for chronic pain: Risks and benefits. Journal of Pain & Palliative Care Pharmacotherapy, 26(1), 68-69.

Hill, K. P. (2015). Medical marijuana for treatment of chronic pain and other medical and psychiatric problems: A clinical review. JAMA, 313(24), 2474-2483.

Indianapolis Business Journal. (2105). Medical-marijuana bill won’t fly this session, but attitudes shift. Retrieved from http:// www.ibj.com/articles/51583-medical-marijuana-bill-wont-fly-thissession-but-attitudes-shift

Kondrad, E. (2013). Medical marijuana for chronic pain. North Carolina Medical Journal, 74(3), 210-211.

Lynne-Landsman, S. D., Livingston, M. D., & Wagenaar, A. C. (2013). Effects of state medical marijuana laws on adolescent marijuana use. American Journal of Public Health, 103(8), 1500-1506.

Moss, H. B., Goldstein, R. B., Chen, C. M., & Yi, H. Y. (2015). Patterns of use of other drugs among those with alcohol dependence: Associations with drinking behavior and psychopathology. Addictive Behaviors, 50, 192-198.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2015). DrugFacts: Nationwide Trends. Retrieved from http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/ drugfacts/nationwide-trends

Pacek, L. R., Martins, S. S., & Crum, R. M. (2013). The bidirectional relationships between alcohol, cannabis, co-occurring alcohol and cannabis use disorders with major depressive disorder: Results from a national sample. Journal of Affective Disorders, 148(2-3), 188-195.

Peters, E. N., Budney, A. J., & Carroll, K. M. (2012). Clinical correlates of co-occurring cannabis and tobacco use: A systematic review. Addiction, 107(8), 1404-1417.

State of New Jersey Department of Health. Medicinal Marijuana Program. (2015).

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2015). Cannabis. Retrieved from http://www.samhsa.gov/atod/ cannabis

Vandrey, R., Raber, J. C., Raber, M. E., Douglass, B., Miller, C., & Bonn-Miller, M. O. (2015). Cannabinoid dose and label accuracy in edible medical cannabis products. JAMA, 313(24), 2491-2493.

Whiting, P. F., Wolff, R. F., Deshpande, S., Di Nisio, M., Duffy, S., Hernandez, A. V., …, Kleijnen, J. (2015). Cannabinoids for medical use: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA, 313(24), 2456-2473.