Quality of Life Among Older People with Multiple Sclerosis

Why is this important to me?

People with MS may experience feelings of helplessness, loss of control, and disabilities that impact their overall quality of life. Daily life is challenging for many older people with MS because of physical and psychological difficulties. Physical challenges often include fatigue, pain, vision problems, muscle weakness, trouble walking, bladder and bowel problems, etc. Psychological problems may include depression, cognitive problems, less social activity, increased dependence on other people, etc. Together, these symptoms affect a person’s health-related quality of life (HRQOL), which is composed of physical and psychological factors. HRQOL measures takes into account physical abilities, capability of performing daily life activities, and overall well-being and satisfaction with life.

How will I benefit from reading this study?

This study examined 211 people with MS who were age 60 or older and who visited one of four MS centers on Long Island, New York. The average age of participants was 65.5 years old, and they had been living with MS for an average of 19.7 years. Regarding MS subtypes, 38% had relapsing-remitting MS, 26% had secondary progressive MS, and 14% had the primary progressive subtype. Most were female (80%) and white (95%). Two-thirds were married, and 13% were widowed. Most (65%) had a caregiver who assisted them with daily activities.

What is the objective of this study?

The purpose of this study was to determine the clinical and demographic factors that were associated with mental and physical HRQOL in older people with MS.

How did the authors study this issue?

Participants were asked to fill out a variety of surveys designed to assess the following factors associated with physical and mental HRQOL:

- Cognitive abilities

- Taking medication as prescribed

- Risk for neuropsychological impairment

- Disability (assessed with self-reported expanded disability status scale)

- Depression

Results showed that participants had a moderate risk of neuropsychological impairment and that 56% were cognitively impaired. Over half could walk 20 yards without resting, and 26% used a wheelchair. Depression was minimal. Overall, participants had better mental than physical health.

The following factors were associated with a decreased mental HRQOL:

- Education level of high school or less

- Risk of neuropsychological impairment

- Disability

- Depression

No factors examined were associated with an improved mental HRQOL.

The following factors were associated with a decreased physical HRQOL:

- Risk of neuropsychological impairment

- Disability

- Depression

- Another illness in addition to MS (called a “co-morbidity”), especially thyroid disease

On the other hand, being employed and being widowed were associated with increased physical HRQOL.

Elderly widows frequently adjust to loss of a loved one differently than younger people, which may explain why being widowed was associated with improved physical HRQOL. The ability to complete daily tasks that a spouse used to do despite having MS may increase physical HRQOL. Thus, older people with MS appear able to adapt and adjust to MS over many years. Remaining employed was also important for quality of life of people with MS. Persistence in remaining employed despite progressive disability due to MS improves quality of life, and thus, employment should be encouraged. Higher education may involve better awareness of MS. Thus, physicians may want to spend more time with patients with less education to improve their understanding of the disease. Increased social isolation due to increasing disability may lead to reduced HRQOL, and thus, rehabilitation and support services may be useful to increase HRQOL in older people with MS. Depression impairs motivation, limits physical ability, and may lead to suicide. Screening for and treating depression in older people with MS is critically important. As people age, they tend to develop more co-morbidities including high blood pressure, heart problems, and thyroid disease, the last of which was associated with decreased physical HRQOL. Little is known about the impact of comorbidities on MS outcomes.

Overall, regular screening and monitoring of older people with MS for physical disability, depression, and cognitive function are needed to identify interventions that will improve physical and mental HRQOL. Each of the US states has an Office for the Aging that provides information about local support services for older individuals.

| SHARE: | |||||

Original Article

Factors Associated with Health-Related Quality of Life Among Older People with Multiple Sclerosis

International Journal of MS Care

Marijean Buhse, PhD, RN, NP; Wendy M. Banker, MPA; Lynn M. Clement, MPH

Background: This study was conducted to determine which factors (clinical and demographic) are associated with mental and physical health-related quality of life (HRQOL) among people with multiple sclerosis (MS) aged 60 years and older.

Methods: Data were collected at four MS centers on Long Island, New York, from a total of 211 patients. Three surveys were administered that collected demographic information and included validated questionnaires measuring quality of life (QOL), cognition, depression, and disability. Multivariate linear regression analyses examined the relationship between patient demographics and scores on standardized scales measuring mental and physical HRQOL (Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life–54). Variables included in the regression models were selected on the basis of the Andersen Healthcare Utilization model. This framework encompasses the multiple influences on health status, including predisposing characteristics, enabling resources, need, and health behavior.

Results: We found that mental HRQOL was negatively associated with having a high school education or less, risk of neurologic impairment, physical disability, and depression. No variables were positively associated with mental HRQOL. Physical HRQOL was negatively associated with risk of neurologic impairment, physical disability, depression, and the comorbidity of thyroid disease. However, patient employment and, surprisingly, being widowed were positively associated with physical HRQOL. These findings are consistent with those of similar studies among younger patients in which lower HRQOL was associated with increased disability, depression, risk of neurologic impairment, and lower levels of education.

Conclusions: The findings that patient employment and being widowed were associated with better physical HRQOL suggest that older patients have the ability to adapt and adjust to the challenges of MS over time. Clinicians should regularly screen for HRQOL in older patients with MS.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a progressive neurologic disease usually diagnosed between the ages of 20 and 50 years.1 Although the lifespan of those with MS has been shown to be shorter than that of age- and sex-matched populations, many people will still age with MS.2 Daily life is challenging for many MS patients because of physical and psychological impairments. Physically, MS patients may experience fatigue, pain, visual impairments, weakness, mobility impairment, and bladder and bowel dysfunction.3–9 Psychologically, they may have impaired cognition, depression, reduced social interaction, and increased reliance on others.4,5,10,11

MS symptoms are burdensome and negatively affect health-related quality of life (HRQOL). In MS, HRQOL is a multidimensional construct that refers to an individual’s physical functioning, ability to perform daily activities, sense of well-being, satisfaction with life, perception of psychological status, and social functioning.12 Past research suggests that HRQOL has both physical and psychological components that interact with each other.12–14 Specifically, HRQOL has been found to be affected by disability, fatigue, and depression in young and middle-aged people with MS.14 Furthermore, middle-aged patients with a secondary progressive disease course are known to have poorer HRQOL.3

Few studies have focused on HRQOL among elderly MS patients. DiLorenzo and colleagues15 compared quality of life (QOL) and mental health challenges in older (mean age 66.1 years) and younger (mean age 47.3 years) individuals with MS (n = 60). Although older patients had greater physical limitations, QOL and mental health were similar in the two groups. Garcia and Finlayson16 found that older people with MS (n = 725) reported fewer mental health challenges than younger ones. Minden et al.17 reported that disability was significantly greater in patients over age 65 compared with a younger group; however, cognitive and emotional problems were significantly lower in the older population. One-third of the group over age 65 reported fair to poor health. Yet Klewer and colleagues7 found that 58% of older adults with MS (n = 53) have frequent depressed feelings and that 30% report having contemplated suicide. Older adults with MS also have to cope with feelings of helplessness, loss of control, and disability-related losses that can affect quality of life.1

Adherence to medications has been shown to affect HRQOL in younger populations of MS patients but remains unexplored in older patients. Cerghet et al.18 found that those patients with MS (average age 54 years) who adhered to their treatment had better mental health and were more likely to be employed and have less disability. Adherence to medications in the elderly with MS has not been described.

Lastly, as people with MS age, they may be prone to the same comorbidities as other aging individuals. Marrie et al.19 reported that the incidences of the most commonly reported comorbidities of MS patients—hypercholesteremia, hypertension, and arthritis—were the same as in the general population. The average age in that study was 53 years. It is important to explore how comorbidities affect the HRQOL of the older person with MS. These diverse studies highlight the need for further exploration of factors associated with HRQOL in older adults with MS.

The present study used the Andersen Healthcare Utilization model to investigate factors associated with mental and physical HRQOL among the aging population with MS. A secondary aim of the study was to characterize the older MS population in terms of demographics, MS clinical features, and HRQOL.

Methods

Participants

MS patients aged 60 years and older were recruited through four MS centers on Long Island, New York. Health-care practitioners at each center explained the research to age-appropriate patients. Inclusion criteria were age 60 years or older and the ability to understand and sign consent forms and complete the surveys. If a patient was physically unable to complete the surveys but had the cognitive ability to do so, he or she could be included in the study if someone else was available to write down the answers. This cognitive ability was determined by the health-care practitioner at each site. Patients with severe cognitive impairment as determined by the health-care practitioner at each site were excluded from the study. A self-selected, convenience sample of patients who expressed an interest in participating were recruited into the study. At the time of recruitment, the patient completed a consent form and an oral Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT) while the health-care practitioner completed a short intake form.20 Patients were also given the option of completing the first survey with the health-care practitioner at this visit.

Data-Collection Procedures

Three different cross-sectional, paper-based surveys, each intended to take 15 minutes to complete, were designed to identify the issues that MS patients aged 60 years and older cope with regularly. Recruitment began in August 2010, and the last completed survey was received in July 2011. As the surveys were lengthy, only the first one was routinely administered during a visit with the health-care provider, with the two subsequent surveys mailed sequentially to the participant’s home immediately after the previous one was returned. If a patient did not return a survey within 2 weeks of its mailing, the investigator made a reminder telephone call. Because of this method of survey administration, the time it took for participants to complete and return all surveys varied.

If the participant chose to complete the first survey at another time, he or she was given a self-addressed, postage-paid envelope to mail it back to the investigators. Upon return of this first survey, the patient was immediately mailed the second survey along with a $20 gift card (which was also sent to those who completed the first survey at the visit) and a postage-paid return envelope. This process was repeated for the third survey, with a $25 gift card. When the patient returned the third survey, a final gift card of $30 was sent in appreciation for completing the study. With the objective of identifying issues that this population faces regularly, sociodemographic data, clinical data, and several validated scales were used to assess a set of health-related measures. SUNY Stony Brook and North Shore University Medical Center provided institutional review board approval for this research.

Measures

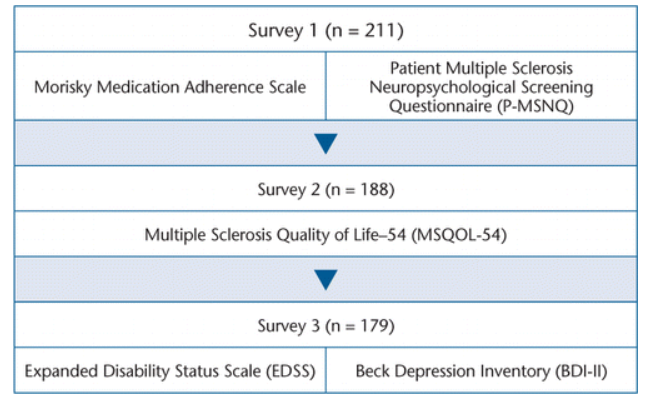

The measures included in each survey as well as the number of completed interviews for each one are shown in Figure 1. The first survey included demographic questions, the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale, and the Patient Multiple Sclerosis Neuropsychological Screening Questionnaire (P-MSNQ). The second survey included the Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life–54 (MSQOL-54), and the final survey included the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) and the self-reported Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS).

Cognitive function was measured using the oral SDMT.20 This was completed at the time of recruitment with the assistance of the health-care practitioner. Respondents were provided with a worksheet containing rows of blank squares, each of which was associated with a symbol. The worksheet also contained a key matching each symbol with a corresponding number. Using the symbol key, respondents were given 90 seconds to verbalize as many numbers as possible. The more correct numbers verbalized, the higher the score, indicating better cognitive function. The published international norms for the SDMT have been validated for use in people aged 60 to 87 years.21

Medication adherence was measured using the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale.22 This scale consists of eight survey items that measure several medication-taking behaviors. The first seven items are yes/no dichotomous responses, whereas the last item is measured using a 5-point Likert scale (“never/rarely” to “all the time”). Scores for this scale range from 0 to 8, with 0 indicating high adherence, 1 to 2 indicating medium adherence, and greater than 2 indicating low adherence. This scale is widely used in the elderly population to measure adherence.23

Risk for neuropsychological impairment was measured using the P-MSNQ.24,25 This scale consists of 15 items rated on a 5-point scale of 0 (never, does not occur) to 4 (very often, very disruptive) that are used to assess frequency and disruption level of several problems patients may experience. Scores range from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating higher risk for neuropsychological impairment. Although there are no age guidelines for this questionnaire, it has been correlated with a higher risk of neuropsychological impairment in many different populations.26,27

Health-related quality of life was measured using the MSQOL-54.27 The scale consists of 54 items: 18 MS-specific items and 36 general health items, which are from the 36-item Short Form Health Status Survey (SF-36). The scale is divided into 12 subscales and has two summary scores: the physical health composite summary and the mental health composite summary. In each of the subscales, a higher score indicates better health. The MSQOL-54 has not been validated in the elderly MS population, but it has been validated in the general MS population.28,29 Additionally, the SF-36 has been shown to be reliable and valid in the general elderly population.30

Disability was measured using the self-reported version of the EDSS.31 This scale includes 19 self-rated items related to walking ability, strength, coordination, sensation, bladder function, vision, swallowing, thinking, and MS disease activity. Scores range from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating more advanced disease. This scale was validated in a sample of MS patients aged 18 to 78 years.31

The presence and severity of symptoms of depression were assessed using the BDI-II.32 This 21-item instrument includes several symptoms of depression, which are rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 to 3, and has a maximum score of 63. Patients with a score of 0 to 13 are considered to have minimal depression; 14 to 19, mild depression; 20 to 28, moderate depression; and 29 to 63, severe depression.

Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata, version 10 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Because of a large quantity of missing data at the sexual function series of questions for the MSQOL-54, we used the second scoring version of the physical health summary, which does not incorporate the sexual function subscale. Standard scoring algorithms were used for all other health-related measures.

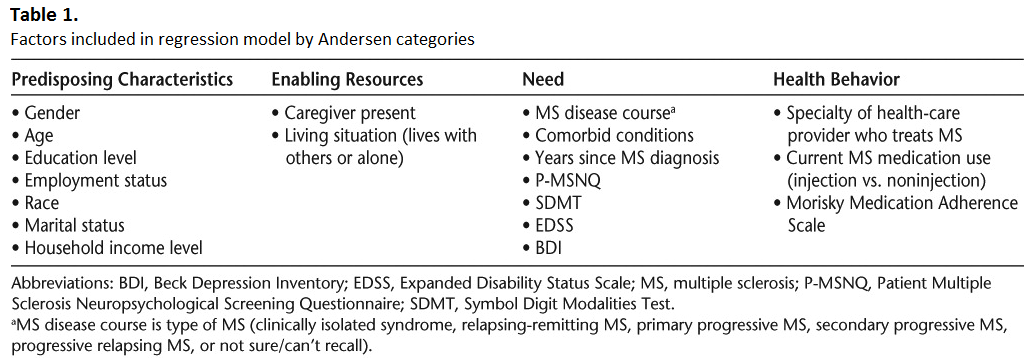

The Andersen Healthcare Utilization model33 domains were adapted to select and categorize variables from the surveys for multivariate regression models. These domains and the variables within each are displayed in Table 1. We used this model because it encompasses the multiple influences on health status, including predisposing characteristics, enabling resources, need, and health behavior. Thus it provides a comprehensive view of the potential influences on HRQOL.

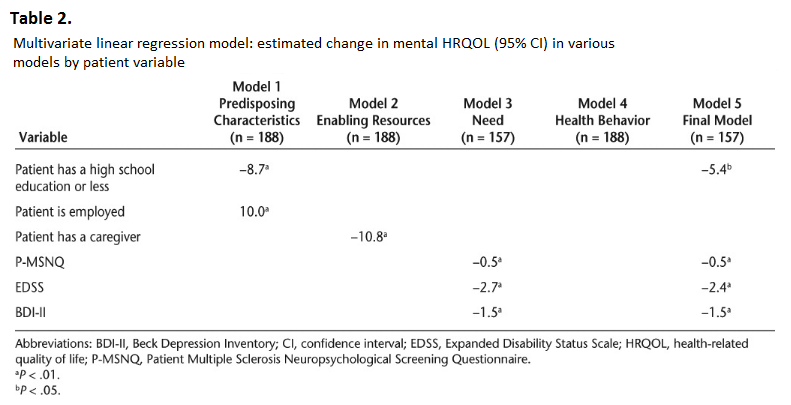

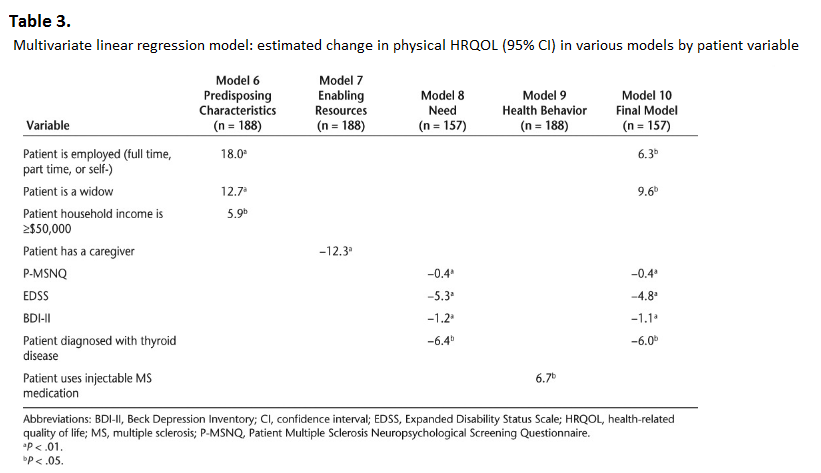

Each regression analysis (variables associated with mental HRQOL [Table 2] and variables associated with physical HRQOL [Table 3]) had two components. The first models (models 1–4 and models 6–9) were constructed using the variables within each Andersen Healthcare Utilization model domain (Predisposing Characteristics, Enabling Resources, Need, and Health Behavior) to determine the association between each of the outcome measures (physical and mental HRQOL from the MSQOL-54) in separate analyses. The final model for each outcome measure (physical [model 10] and mental [model 5] HRQOL) used the independently significant predictors found in the first models (mental HRQOL [models 1–4] and physical HRQOL [models 6–9]).

The regression coefficients in the models represent the extent to which the mean MSQOL physical and mental scores (dependent variable) are expected to decrease (if the coefficient is negative) when specific factors (independent variables) are present, keeping other independent variables constant. Sample sizes varied by regression model (n = 157 to n = 188), as some variables had missing data. Statistical significance was measured using the likelihood ratio test and was defined as P < .05 or P < .01.

Results

Respondent Demographic Characteristics

A total of 211 patients participated in the study between August 2010 and July 2011. Specifically, 211 patients returned the first survey, 188 the second, and 179 the third. The overall attrition rate was 15% from the first to the third survey. Because of the uniqueness of the study, we cannot provide a comparable attrition rate for this type of research. In addition, because the surveys were paper-based, response rates varied by question, as patients could leave an individual question blank. The 95% confidence interval (CI) for the sample at the final stage of n = 179 is ±0.073249. The reliability of the study sample is estimated with a 95% CI of ±0.073.

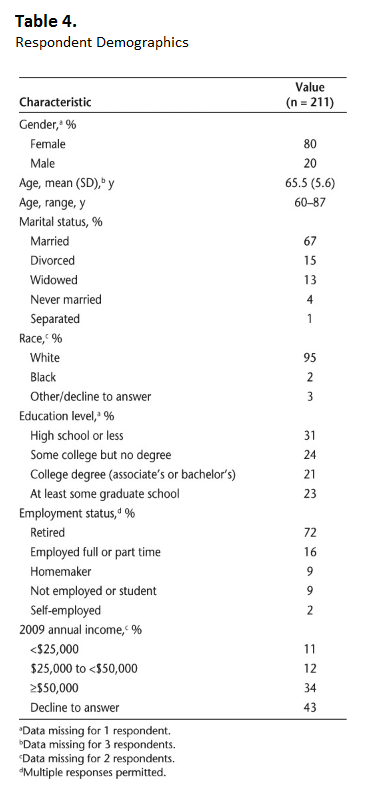

Respondent demographics were self-reported and are displayed in Table 4. On average, respondents were 65.5 (SD 5.6) years old. The majority were female (80%), and nearly all were white (95%). Two-thirds were married (67%), one-eighth were widowed (13%), and nearly three-quarters were retired (72%). Respondents were more likely to be currently living with their spouse (65%) than alone (18%) or with their children (17%).

Sixty-five percent of respondents had a caregiver who assisted them with their everyday activities. Of those, 83% reported that their caregiver lived with them. Care givers were most frequently the patient’s spouse (70%), a paid caregiver (12%), or a child (6%).

The most common comorbidities reported by respondents were high cholesterol (46%), hypertension (45%), arthritis (33%), depression (31%), and thyroid disease (20%). All but one respondent (99.5%) reported that they were covered by health insurance, and 98% of those indicated that their health plan provided prescription drug coverage.

MS Clinical Characteristics

On average, patients reported that they had been diagnosed with MS 19.7 (SD 12.3) years previously. Thirty-eight percent of respondents reported that they had relapsing-remitting MS, 26% had secondary progressive MS, and 14% had primary progressive MS.

In terms of treatments for their disease, respondents were most likely to be currently taking interferon beta-1a (23%), glatiramer acetate (21%), interferon beta-1b (13%), or natalizumab (7%). On the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale, the majority (62%) were classified as medium adherers to their injectable MS medication. Further, 20% were low adherers and 18% were high adherers. The most frequent adherence issues among patients using an injectable MS medication were feeling hassled about the treatment plan (17%), not taking the last dose (15%), and sometimes forgetting to take the medication (13%).

Health-Related Measures

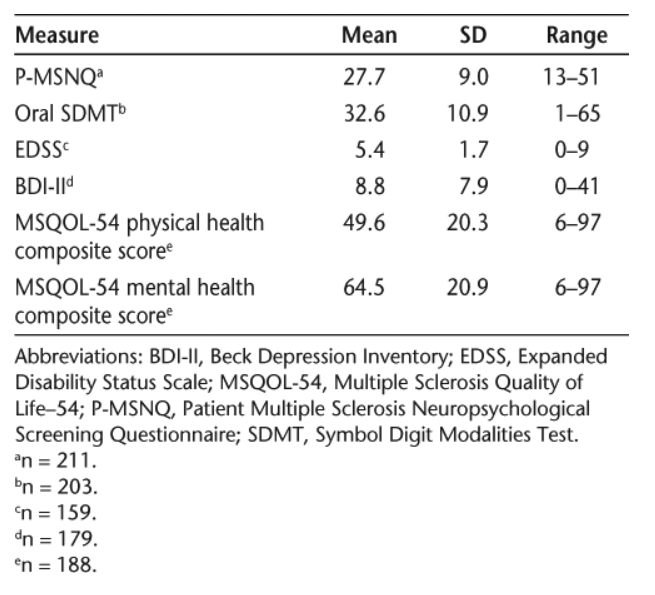

Table 5 presents the mean scores, standard deviations, and ranges for the P-MSNQ, oral SDMT, EDSS, BDI-II, and MSQOL-54 physical and mental health composite scores. The mean P-MSNQ score among all patients was 27.7 (SD 9.0), indicating that the average respondent had a moderate risk of neuropsychological impairment. In addition, 56% of respondents’ self-reported scores classified them as being cognitively impaired (score of higher than 24).4 According to the SDMT’s classifications, the patients in our sample were cognitively impaired. On average, they scored 32.6 (SD 10.9) on the oral SDMT, which is lower than the average for healthy volunteers aged 55 to 75 (SDMT mean range, 46.2–48.4).34 The mean EDSS score among respondents was 5.4 (SD 1.7). Eighteen percent of respondents were fully ambulatory without aid and self-sufficient for up to 12 hours a day (EDSS 0 to <4). Just over half (56%) were able to walk at least 20 yards without resting (EDSS 4 to <7), and 26% were largely confined to a wheelchair (EDSS ≥7). On average, respondents had a BDI-II score of 8.8 (SD 7.9), indicating minimal depression. Using the standard BDI-II categories, 76% of respondents were minimally depressed (score of 0–13), 10% were mildly depressed (score of 14–19), 13% were moderately depressed (score of 20–28), and 1% were severely depressed (score of 29–63). According to the MSQOL-54, respondents were in better mental health (mean 64.5, SD 20.9) than physical health (mean 49.6, SD 20.3).

Association Between Patient Health Factors and Quality of Life

Table 2 presents the multivariate associations observed between the Predisposing Characteristics, Enabling Resources, Need, and Health Behavior variables as well as the final combined model and patient mental HRQOL (MSQOL-54 mental health composite score). The following variables were significantly associated with a decreased mental HRQOL in the final model: education level (high school or less) (Predisposing Characteristic), risk of neuropsychological impairment (P-MSNQ score) (Need), disability status (EDSS score) (Need), and level of depression (BDI-II score) (Need). None of the variables were found to be associated with an increased mental HRQOL.

Table 3 presents the multivariate associations between the Predisposing Characteristics, Enabling Resources, Need, and Health Behavior variables as well as the final combined model and patient physical HRQOL (MSQOL-54 physical health composite score). The following variables were significantly associated with a decreased physical HRQOL in the final model: risk of neuropsychological impairment (P-MSNQ score) (Need), disability status (EDSS score) (Need), level of depression (BDI-II score) (Need), and presence of a comorbid condition (diagnosed by a health-care provider with thyroid disease) (Need). On the other hand, the following variables were found to be significantly associated with increased physical HRQOL in the final model: employment status (employed) and marital status (widowed) (Predisposing Characteristics).

Discussion

In this study of older patients with MS, we found that Predisposing Characteristics—specifically, being widowed, remaining employed, and education level—were the strongest predictors of better QOL. Physical HRQOL was positively associated with the patient being widowed and being employed, while mental HRQOL was negatively associated with having a high school education or less. Need characteristics were the strongest predictors of a decrease in QOL. Patient disability status (EDSS) was found to be negatively associated with both physical and mental HRQOL.

Elderly individuals who are widowed have often been reported to have lower QOL as a result of the effects of social isolation and loneliness.35 However, Carr and Utz36 found that elderly widows adjust to loss very differently and may not be as grief-stricken as their younger counterparts. The widow must take on responsibilities that had been shared by both spouses and modify routines, daily decisions, and household duties. The ability to complete these tasks daily despite having MS may increase physical HRQOL. Elderly individuals with MS have reported their ability to adapt and adjust to MS over many years, and being independent and remaining at home is highly valued.37 These results are similar to the findings from the Sonya Slifka Longitudinal Multiple Sclerosis Study, in which it was shown that patients over age 65 years often lived alone but viewed their health status positively, thus appearing to adapt over time despite the progression of disease.17

This sample of patients was slightly different from the overall MS population, as women made up 80% of this study, compared with approximately 66% of the overall MS population. Also, 95% were white, which is also dissimilar to the overall MS population; however, this may be attributed to the recruitment area, a suburb of New York City.

Although our sample consisted of people aged 60 and older, 16% worked either full or part time. Being employed was positively associated with physical HRQOL. These results are similar to those found in the larger MS population: past research has found that MS patients who are employed have higher HRQOL than those who are unemployed.38,39 Such findings suggest that remaining employed is very important in maintaining the QOL of the MS patient. Strober et al.40 found that employed MS patients have a higher level of persistence, defined as the degree to which someone is hardworking, industrious, and stable despite frustration and fatigue. Other studies on employment in MS have shown that those patients who remain employed have better self-reported quality of life.40,41 Thus older MS patients should be encouraged to stay employed as long as possible.

The education level of the older MS patients in our study was found to be associated with mental HRQOL. Specifically, less education (high school or less, compared with at least some college) was negatively associated with mental HRQOL. Previous research among younger MS patients has also found less education to be associated with lower mental HRQOL.38,39 Patti et al.38 concluded that mental HRQOL is significantly influenced by level of education in MS patients and that higher level of education may result in better awareness of the disease as well as an increased ability to cope with its challenges. Aging patients with lower educational levels may need more time with their health-care providers to understand the impact, management, and treatment of MS. Patients can also be directed to the National Multiple Sclerosis Society website (http://www.nationalmssociety.org) for details on support groups and further information about MS.

Previous research has found patient physical disability to be associated with poorer overall HRQOL.42–45 Patient physical disability has also been found to be associated with mental health challenges as well as reduced physical HRQOL.5,16,42 Older adults with MS may be more isolated, be less able to leave their homes, and have less social support than younger individuals with MS. Lack of social support, disabling symptoms, and social isolation have been reported as negative aspects of aging with MS.46 Encouraging the use of rehabilitation services and participation in MS support groups may help increase elderly patients’ HRQOL by helping them cope with their physical disability.

Both mental and physical HRQOL were negatively associated with patient depression (BDI-II). Depression has been found to be a significant predictor of low HRQOL in past research.12,42 Specifically, depression affects both the mental and physical domains of HRQOL, as it impairs motivation and interest and limits physical progress.12 Depression is common in elderly patients with chronic diseases who live in the community, with more than one-quarter experiencing symptoms.47 Older adults with MS may face different problems than younger people with MS, which can predispose them to depression. These include limited social support, role transitions, changes in relationships, and decreased accessibility of the environment.11 For some older adults, depression may lead to suicide.48 Thus screening for and treating depression in older adults with MS is essential.

In our study, mental and physical HRQOL were found to be negatively associated with patient risk of cognitive impairment (P-MSNQ), and most patients were cognitively impaired according to the SDMT. While patient cognition as measured using the P-MSNQ was significantly associated with both mental and physical HRQOL, the SDMT score was not. Conversely, prior research found that among younger individuals with MS, lower SDMT scores were significantly associated with poorer HRQOL.13,49 However, two recent studies involving younger MS patients revealed weak correlations between HRQOL and cognitive impairment.50,51

Elderly people with MS appear to be similar to other older people with cognitive impairment. Among elderly people with dementia, QOL is associated with mood, engagement in pleasant activities, and the ability to perform activities of daily life (ADLs), whereas for a younger person with MS, cognitive impairment is associated with poor QOL in relation to working, interpersonal relationships, and leisure activities.12,52 This may be related to the older person being able to adapt and adjust his or her lifestyle to MS over time. Interventions such as cognitive stimulation and rehabilitation services should be used for elderly MS patients with cognitive impairment. Although according to the SDMT the sample in this study was cognitively impaired, this should not affect their self-report. Gold et al.53 studied cognitively impaired MS patients and their ability to accurately self-report and found that QOL and affective symptomatology can be reliably assessed in MS patients with cognitive impairment. Sprangers et al.54 compared QOL in young, middle-aged, and older people with numerous chronic diseases and found that patients who were older, had a lower level of education, and had at least one comorbid condition had the lowest QOL. In our study, one comorbid condition, thyroid disease, was negatively associated with physical HRQOL.

The influence of comorbidity on HRQOL is important. In the general population, patients with comorbid conditions reported the lowest levels of physical and mental HRQOL.55 As individuals with MS age, they are likely to have the same comorbidities as the general population, including hypertension, heart conditions, diabetes, and even thyroid disease.37 These comorbidities may also lead to other related illnesses. Ploughman et al.37 reported that older people with MS are very concerned about comorbid conditions and the effects on their lifestyle. Aging individuals with MS must have a primary health-care provider who will manage comorbid conditions appropriately. Encouraging them to obtain age-related screenings and management of disease may reduce the impact of the comorbidity. While significant progress has been made in the clinical management of common chronic diseases, much less is known about the impact of comorbidity—including both physical and mental health comorbidities—on disease management and clinical outcomes.55

Finally, adherence to injectable medications had no impact on HRQOL in this sample of older MS patients. The majority of patients (62%) were medium adherers, meaning that they took their injectable medication as prescribed most of the time (the most common therapy was interferon beta-1a). In studies of QOL in younger MS patients on interferon medications, findings were similar, with no impact of the medication on HRQOL.56,57

Limitations

Although this study involved a very large sample of older patients with MS, the findings must be interpreted within the context of limitations. First, the study participants were drawn from a convenience sample from four MS centers on Long Island, New York. Two centers were in academic health centers, and two were private practices. Participation was voluntary; therefore, this nonrandom sample may result in self-selection bias. Second, the self-report design of the study is a potential limitation because people might provide answers that they think they should provide rather than those that are true.58 Self-report can also leave room for response bias; however, this may be the only way for a researcher to obtain this type of information about the patient.

Third, this study did not include the many individuals with MS who do not go to MS centers for their health care or who reside in nursing homes. This may also bias the study toward patients who are able to be home (with or without a caregiver) and those who seek specialized MS care.

Moreover, the study sample was from a suburban area outside of New York City. There may be differences in the care patients receive in other areas of the country or outside of the United States; the results cannot be generalized to the entire population of elderly MS patients. Finally, we used the BDI-II, which was not specifically designed for use among elderly people. There are geriatric depression scales that may be more useful in future studies when determining risk for depression in this population.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates the various influences on HRQOL in an aging population of MS patients. Specifically, HRQOL was found to be significantly associated with physical disability, depression, cognition, being employed, being a widow, having been diagnosed with thyroid disease, and level of education. These findings support the regular screening and monitoring of older MS patients for physical disability, depression, and cognitive impairment. Early detection and intervention may help improve patients’ physical and mental HRQOL. In addition, as lower level of education is negatively associated with mental HRQOL, health-care providers may want to spend more time with these patients to help them better understand their disease and cope with its impact on their lives.

In the United States, each state has an Office for the Aging that can provide specific information about local support services for the elderly. Health-care practitioners should have information available to give to any patient who may benefit from these services.

PracticePoints

- Clinicians should regularly screen older patients with MS for health-related quality of life (HRQOL).

- Depression and cognitive impairment should be assessed regularly in such patients because of their influence on both physical and mental HRQOL.

- Aging MS patients should have a primary-care provider who manages comorbid conditions appropriately. Age-related screenings and disease management may reduce the impact of comorbidities on overall HRQOL.

References

1.Finlayson M. Concerns about the future among older adults with multiple sclerosis. Am J Occup Ther. 2004; 58: 54–63.

2.Redelings MD , McCoy L , Sorvillo F. Multiple sclerosis mortality and patterns of comorbidity in the United States from 1990 to 2001. Neuroepidemiology. 2006; 26: 102–107.

3.Beiske A , Naess H , Aarseth J , et al. Health-related quality of life in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2007; 13: 386–392.

4.Benedict RH. Integrating cognitive function screening and assessment into the routine care of multiple sclerosis patients. CNS Spectr. 2005; 10: 384–391.

5.Goretti B , Portaccio E , Zipoli V , et al. Coping strategies, psychological variables and their relationship with quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci. 2009; 30: 15–20.

6.Douglas C , Wollin JA , Windsor C. The impact of pain on the quality of life of people with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2009; 11: 127–136. [Abstract]

7.Klewer J , Pohlau D , Haas J , Kugler J. Problems reported by elderly patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2001; 33: 167–171.

8.Pawar VS , Pawar G , Miller LA , et al. Impact of visual impairment on health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2010; 12: 83–91. [Abstract]

9.Finlayson M. Health and social profile of older adults with MS: findings from three studies. Int J MS Care. 2002; 4: 139–151. [Abstract]

10.Patti F , Amato M , Trojano M , et al. Quality of life, depression, and fatigue in mildly disabled patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis receiving subcutaneous interferon beta-1a: 3-year results from the COGIMUS study. Mult Scler J. 2011; 17: 991–1001.

11.Fong T , Finlayson M , Peacock N. The social experience of aging with a chronic illness: perspectives of older adults with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2006; 28: 695–705.

12.Mitchell AJ , Benito-Leon J , Morales Gonzalez JM , Rivera-Navarro J. Quality of life and its assessment in multiple sclerosis: integrating physical and psychological components of wellbeing. Lancet Neurol. 2005; 4: 556–566.

13.Hoogs M , Kaur S , Smerbeck A , Biana WG , Benedict RHB. Cognition and physical disability in predicting health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2011; 13: 57–63. [Abstract]

14.Janardhan V , Bakshi R. Quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis: the impact of fatigue and depression. J Neurol Sci. 2002; 205: 51–58.

15.DiLorenzo T , Terry D , Halper J , Picone MA. Comparison of older and younger individuals with multiple sclerosis: a preliminary investigation. Rehabil Psychol. 2004; 49: 123–125.

16.Garcia J , Finlayson M. Mental health and mental health service use among people aged 45+ with multiple sclerosis. Can J Commun Ment Health. 2005; 24: 9–22.

17.Minden S , Frankel D , Hadden L , Srinath K , Perloff J. Disability in elderly people with multiple sclerosis: an analysis of baseline data from the Sonya Slifka Longitudinal Multiple Sclerosis Study. NeuroRehabilitation. 2004; 19: 55–67.

18.Cerghet M , Dobie E , Lafata J , et al. Adherence to disease-modifying agents and association with quality of life among patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2010; 12: 51–58. [Abstract]

19.Marrie R , Horwitz R , Cutter G , Tyry T , Campagnolo D , Vollmer T. Comorbidity, socioeconomic status and multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2008; 14: 1091–1098.

20.Smith A. The Symbol Digit Modalities Test: A Neuropsychologic Test of Learning and Other Cerebral Disorders. Seattle, WA: Special Child Publications; 1968.

21.Vogel A , Stokholm J , Jorgensen K. Performances on Symbol Digit Modalities Test, Color Trails Test and modified Stroop test in a healthy, elderly Danish sample. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn. 2013; 20: 370–382.

22.Morisky DE , Ang A , Krousel-Wood M , Ward HJ. Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens. 2008; 10: 348–354.

23.Krousel-Wood M , Muntner P , Islam T , Morisky D , Webber L. Barriers to and determinants of medication adherence in hypertension management: perspective of the Cohort Study of Medication Adherence Among Older Adults. Med Clin North Am. 2009; 93: 753–769.

24.Benedict RH , Munschauer F , Linn R , et al. Screening for multiple sclerosis cognitive impairment using a self administered 15-item questionnaire. Mult Scler. 2003; 9: 95–101.

25.Benedict R , Cox D , Thompson L , Foley F , Weinstock-Guttman B , Munschauer F. Reliable screening for neuropsychological impairment in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2004; 10: 675–678.

26.Sonder J , Mokkink L , van der Linden G , Polman C , Uitdehaag B. Validation and interpretation of the Dutch version of the Multiple Sclerosis Neuropsychological Screening Questionnaire. J Neurol Sci. 2012; 320: 91–96.

27.Vickrey B , Hays R , Harooni R , Myers L , Ellison G. A health-related quality of life measure for multiple sclerosis. Qual Life Res. 1995; 4: 187–206.

28.Ackbar N , Honarmand K , Kou N , Levine B , Rector N , Feinstein A. Validity of an internet version of the Multiple Sclerosis Neuropsychological Screening Questionnaire. Mult Scler. 2010; 16: 1500–1506.

29.Heiskanen S , Merilainen P , Pietila A. Health-related quality of life testing the reliability of the mSQOL-54 instrument among MS patients. Scand J Caring Sci. 2007; 21: 199–206.

30.Lyons R , Perry I , Littlepage B. Evidence for the validity of the short-form 36 questionnaire (SF-36) in an elderly population. Age Aging. 1994; 23: 182–184.

31.Bowen J , Gibbons L , Gianes A , Kraft GH. Self administered Expanded Disability Status Scale with functional system scores correlates well with a physician-administered test. Mult Scler. 2001; 7: 201–206.

32.Beck AT , Steer RA , Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory-II Manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996.

33.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995; 36: 1–10. [CrossRef]

34.Cetofani C. Selected Somatosensory and Cognitive Test Performances as a Function of Age and Education in Normal and Neurologically Impaired Adults [dissertation]. University of Michigan; 1975.

35.Coyle C , Dugan E. Social isolation, loneliness and health among older adults. J Aging Health. 2012; 24: 1346–1363.

36.Carr D , Utz R. Late-life widowhood in the United States: new directions in research and theory. Ageing Int. 2002; 27: 65–88.

37.Ploughman M , Austin MW , Murdoch M , et al. Factors influencing healthy aging with multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2012:34:26–33.

38.Patti F , Montanari E , Pappalardo A , et al. Effects of education level and employment status on HRQoL in early relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2007; 13: 783–791.

39.Miller A , Dishon S. Health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis: the impact of disability, gender and employment status. Qual Life Res. 2006; 15: 259–271.

40.Strober LB , Christodoulou C , Benedict RH , et al. Unemployment in multiple sclerosis; the contribution of personality and disease. Mult Scler. 2012; 18: 647–653.

41.Krokavcova M , Nagyova I , Rosenberger J , et al. Employment status and perceived health status in younger and older people with multiple sclerosis. Int J Rehabil Res. 2012; 35: 40–47.

42.Karatepe AG , Kaya T , Gunaydin R , Demirhan A , Ce P , Gedizlioglu M. Quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis: the impact of depression, fatigue, and disability. Int J Rehabil Res. 2011; 34: 290–298.

43.Twork S , Wiesmeth S , Spindler M , et al. Disability status and quality of life in multiple sclerosis: non-linearity of the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010; 8: 5–11.

44.Nortvedt MW , Riise T , Myhr KM , Nyland HI. Quality of life as a predictor for change in disability in MS. Neurology. 2000; 55: 51–54.

45.Zwibel HL. Contribution of impaired mobility and general symptoms to the burden of multiple sclerosis. Adv Ther. 2009; 26: 1043–1057.

46.Finlayson M , Van Denend T , DalMonte J. Older adults' perspectives on the positive and negative aspects of living with multiple sclerosis. Br J Occup Ther. 2005; 68: 117–124.

47.Steffens DC , Skoog I , Norton MC , et al. Prevalence of depression and its treatment in an elderly population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000; 57: 601–607.

48.Blazer DG. Depression in late life: review and commentary. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003; 58: 249–265.

49.Mitchell AJ , Kemp S , Benito-Leon J , Reuber M. The influence of cognitive impairment on health-related quality of life in neurological disease. Acta Neuropsychiatrica. 2010; 22: 2–23.

50.Glanz BI , Healy BC , Rintell DJ , Jaffin SK , Bakshi R , Weiner HL. The association between cognitive impairment and quality of life in patients with early multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2010; 290: 75–79.

51.Baumstarck-Barrau K , Simeoni MC , Reuter F , et al. Cognitive function and quality of life in multiple sclerosis patients: a cross sectional study. BMC Neurol. 2011; 11:17.

52.Logsdon RG , McCurry SM , Teri L. Evidence-based interventions to improve quality of life for individuals with dementia. Alzheimers Care Today. 2007; 8: 309–318.

53.Gold SM , Schulz H , Mönch A , Schulz KH , Heesen C. Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis does not affect reliability and validity of self-report health measures. Mult Scler. 2003; 9: 404–410.

54.Sprangers MAG , de Regt EB , Andries F , et al. Which chronic conditions are associated with better or poorer quality of life? J Clin Epidemiol. 2000; 53: 895–907.

55.Bierman A , Spector W , Atkins D. Improving the Health and Health Care of Older Americans. US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. http://www.ahrq.gov/research/olderam/oldam1.htm. Accessed 2012.

56.Abolfazli R , Hosseini A , Gholami K , Torkamandi H , Emami S. Quality of life assessment in patients with multiple sclerosis receiving interferon beta-1a: a comparative longitudinal study of Avonex and its biosimilar CinnoVex. ISRN Neurol. 2012; 2012:786526.

57.Vermersch P , De Seze J , Delisse B , Lemaire S , Stojkovic T. Quality of life in multiple sclerosis: influence of interferon-beta 1a (Avonex) treatment. Mult Scler. 2002; 8: 377–381.

58.McDonald J. Measuring personality constructs: the advantages and disadvantages of self-reports, informant reports and behavioural assessments. Enquire. 2008; 1: 1–18.

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/Support: Funding for this research was provided by Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals.