Online Depressive Symptom Self Management

People with multiple sclerosis have a 50% lifetime prevalence for depression, which is greater than in other neurological diseases and 3 times higher than the rate for the general population. The goals of the study were to evaluate participant engagement and effects of an Internet-based, self-directed program for depressive symptoms.

Original Article

Online Depressive Symptom Self-Management: Comparing Program Outcomes for Adults With Multiple Sclerosis Versus Those With Other Chronic Diseases

Kiira Tietjen, Marian Wilson, Solmaz Amiri, Jeremy Dietz

Journal of Neuroscience Nursing

Abstract

Aims: The goals of the study were to evaluate participant engagement and effects of an Internet-based, self-directed program for depressive symptoms. We compared outcomes of adults with multiple sclerosis (MS) with those of adults with other chronic diseases.

Methods: This was a secondary analysis of a randomized controlled pilot study. Data were explored for differences between people diagnosed with MS and those with other chronic disease diagnoses. Data were obtained from 47 participants who participated in the original parent study (11 had MS). Participants with at least a moderate preexisting depressive symptom burden on the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) were randomly divided into either a control group or the 8-week ‘‘Think Clearly About Depression’’ online depression self-management program. Study tools were administered at baseline, week 4, and week 8 to evaluate whether the online program improved depressive symptom self-management. Analysis examined differences between participants with and without an MS diagnosis in the treatment and control groups.

Results: Average baseline depressive symptom burdens were severe for those with MS and those without MS as measured by the PHQ. Number needed to treat analysis indicated that 1 in every 2 treatment group participants with MS found clinically significant reductions in depressive symptoms by week 8. All participants with MS completed all online program modules. When compared with those with other chronic diseases, participants with MS showed a trend toward greater improvements in the PHQ and health distress scores in addition to self-efficacy in exercising regularly, social/recreational activities, and controlling/managing depression at the end of 8 weeks.

Conclusions: An online depressive symptom self-management program is acceptable to people with MS and may be helpful to address undertreated depressive symptoms. The number of participants limits available statistics and ability to generalize results.

People with multiple sclerosis (MS) have a 50% lifetime prevalence for depression, which is greater than in other neurological diseases and 3 times higher than the rate for the general population.1 Depression impacts the overall quality of life for people with MS, more so than fatigue, sleep, or mobility status.2,3 This depression does not spontaneously remit4 and is independent of duration of MS disease and disease-related variables.1,2 The suicide rate for people with MS is 7 times that for the general population, with young men in their first 5 years after diagnosis being the highest-risk group.1 Despite these serious sequelae, people with MS are not getting adequate treatment of their depression. An estimated 70% of the general population who screens positive for depression does not receive any treatment.5 This pattern of undertreatment is also observed within populations diagnosed with MS.

Further clouding the treatment of depression for people with MS is that diagnosis may be complicated. Many MS symptoms can overlap with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder (MDD).6 No tools have been adequately analyzed for accuracy in differentiating symptoms of depression from symptoms of MS.7 When depression coexists with any chronic medical condition, it is associated with increased symptom burden, functional impairment, medical costs, poor adherence to self-care regimes, and increased risk of morbidity and mortality

Background

Two practical obstacles exist in diagnosing and treating people with MS and coexisting MDD: one, is MDD recognition, and the other is providing appropriate and effective treatment once diagnosed with MDD. Psychotherapy and antidepressant medication are known to be efficacious for depressive symptoms, yet treatment gaps persist particularly for people of lower income and education and racial/ ethnic minorities and the uninsured.5 More people with MS are now receiving treatment for depression, but the treatment may be inadequate and does not necessarily align with clinical guidelines.9 People with MS whose depression is managed by their neurologist are often not getting antidepressant treatment, and of those receiving antidepressants, some are getting subtherapeutic doses.10 Insufficient research has been conducted within the MS population to support any particular pharmacologic or psychotherapeutic treatment of depression.7

Depression treatment can have important effects on overall MS disease outcomes. Disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) are medications used to attempt to cease the progression of MS. Studies have shown that people with depression are half as likely to be adherent to their DMT and that 63% of people with a mood or anxiety disorder miss their DMT more than 10% of the time.11,12 Yet, when people with MS are adherent to antidepressant treatment, adherence to DMT also improves regardless of overall disability burden, age, or level of education.11,12

One evidence-based treatment of depression is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). It is a common form of psychotherapy that aims to challenge maladaptive cognitions to affect positive change in how a person responds to behavioral problems or emotional distress. The goal of CBT is a reduction of depressive symptoms.13 It has been widely studied and has found to be effective.14 Hind et al’s4 systematic review concluded that CBT was an effective treatment of depression in people with MS but that more trials were needed to explore treatment modality, long-term treatment effects, drug and active comparisons with CBT, cost-effectiveness, and disease-specific qualityof-life outcomes. Only 7 rigorous studies were evaluated in the systematic review.4 Three used CBT individually (1 face-to-face and 2 via telephone), three used CBT in a group setting, and 1 used CBT via computer. Studies conducted with CBT for people with MS showed a median treatment length of 8 weeks and a completion rate of greater than 90%. Of the studies found in the literature review, the 1 computerized program used eight 50-minute online sessions of CBT.15

Objective

In an attempt to address treatment gaps regarding depressive symptoms within the MS population, we conducted a secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) that piloted an online depressive symptom self-management program. The original RCT was conducted on people (N = 47) with any chronic diagnosis to address undertreated depressive symptoms within this broad population.16 The RCT examined willingness to engage in the intervention, satisfaction with the program, and effects on depressive symptoms, health distress, and self-efficacy of depressive symptom management. The study determined that the groups most willing to participate and engage in the program were people with chronic pain (n = 20, 42%) and MS (n = 11, 23%). In this study, we separated data of those enrolled who had MS and compared them with the larger study pool. Our objective was to determine whether unique information could be revealed to inform future treatment options for those with MS and coexisting depressive symptoms.

Methods

Design and Sample

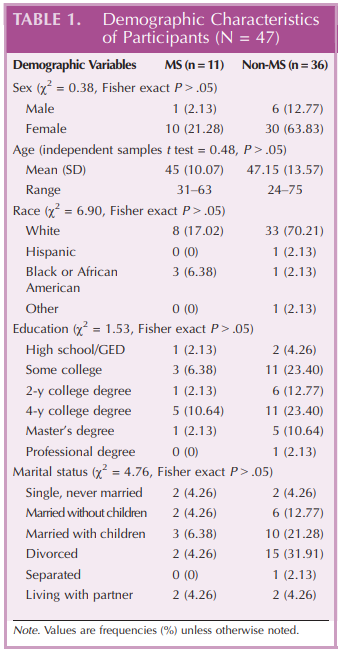

Secondary analyses were conducted on data previously collected from an institutional-review-boardYapproved intervention pilot study.16 The original study was an RCTexamining feasibility and efficacy of Think Clearly About Depression,17 an 8-week online program. US adults were enrolled after screening positive for depressive symptoms and a chronic illness diagnosis of any kind. The final sample for this study analysis divides the 47 participants who completed the parent study procedures into 2 dichotomous groups: one with an MS diagnosis (n = 11) and one without an MS diagnosis (n = 36; see Table 1).

Intervention and Measurements

The selected online program is publicly available for a $20 fee and was created by psychologists with funding from the National Institute of Mental Health.17 The program is based on tested CBT concepts with a primary goal of being to teach mildly or moderately depressed individuals about the role of thinking in the development and maintenance of depression. Details of the program are available online.17 Recognition and self-management of depressive symptoms are encouraged through educational videos, interactive activities, and homework exercises.

Measures

Sociodemographic and health history variables were collected at baseline using an online survey and included age, sex, educational level, chronic disease diagnoses, medications, and psychological counseling history. All participants completed the following scales at baseline and weeks 4 and 8: (1) the Personal Health Questionnaire Depression Scale (PHQ-8), (2) the Health Distress Scale, (3) the Self-Rated Health Scale, and (4) the Chronic Disease Self-Efficacy Scales.

The PHQ-9 is a 9-question scale used to measure depressive symptom severity, whereby the sum of the patient’s responses indicates the severity of symptoms. A shortened version, the PHQ-8, was used in this study, thereby omitting the final item that asks how often you have been bothered by thoughts that you would be better off dead or of self-harm. The PHQ-8 is preferred in online research where an immediate response to self-harm disclosure may not be possible. Scores greater than 14 indicate moderately severe depressive symptoms. Published internal reliability scores are 0.86 to 0.92.18

The Health Distress Scale measures emotional distress related to having a chronic disease and provides insight into how much one’s chronic illness impacts emotional status. It uses a 6-point Likert scale with 4 questions asking how much time during the past month one’s disease caused various emotional responses (0, none of the time, to 5, all of the time). Higher sum scores indicate more distress. The scale has a test-retest reliability of 0.87.19

The Self-Rated Health Scale is a single 5-point Likert item measuring a patient’s self-perceived health status. It asks patients in general how good their health is, with 1 indicating ‘‘excellent’’ and 5 indicating ‘‘poor.’’ Lower scores are more favorable. The scale has a reported testretest reliability of 0.92.20

The Chronic Disease Self-Efficacy Scales consist of 10 Likert scales each measuring a patient’s confidence in conducting activities in his/her disease management and general life. Each question is rated on a 10-point scale ranging from 1 (‘‘not at all confident’’) to 10 (‘‘totally confident’’). The score of each of the 10 scales is the mean of the responses, with higher scores indicating greater confidence. Internal reliability scores have been reported between 0.77 and 0.92.19

Statistical Analysis

Univariate analyses were composed of descriptive statistics with measures of central tendency and variability for continuous variables and frequency distributions and percentages for categorical variables. Bivariate statistics included 22 statistics and independent samples t tests to test for differences in sociodemographic characteristics between the 2 groups: MS and non-MS. Number needed to treat (NNT) analysis was performed to determine how many people with MS would need to be engaged in the intervention to receive a clinically significant improvement (predetermined to be a reduction of 4 points or more on the PHQ-8).20 Trends in treatment effects were assessed by subtracting the difference in mean scores between baseline and week 8. Because of the small sample size, no significance testing was performed.

Results

Analyses of 22 statistics (categorical variables) and independent samples t tests (continuous variables) showed insignificant differences in demographic characteristics when comparing MS and non-MS cohorts (Table 1).

Depression

Of the 11 participants with a diagnosis of MS, 10 (91%) stated that they received some sort of therapy or pharmacological treatment of depressive symptoms at some point in time. Four participants (36%) claimed to be on an antidepressant at the time of the study. Self-report medication lists revealed that 10 (91%) were taking medications with antidepressant effect: 4 on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) alone, 2 on serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor alone, 1 on SSRI and atypical antidepressant, 1 on serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor and atypical antidepressant, and 1 on SSRI and atypical antipsychotic. In addition to pharmacological treatments, 8 (73%) reported some sort of counseling, talk therapy, or behavioral therapy in the past, but none was receiving counseling at the time of study enrolment as a condition of eligibility. Five (45.5%) reported being on a DMT to treat their MS. The DMTs reported included injectable, oral, and infusion medications.

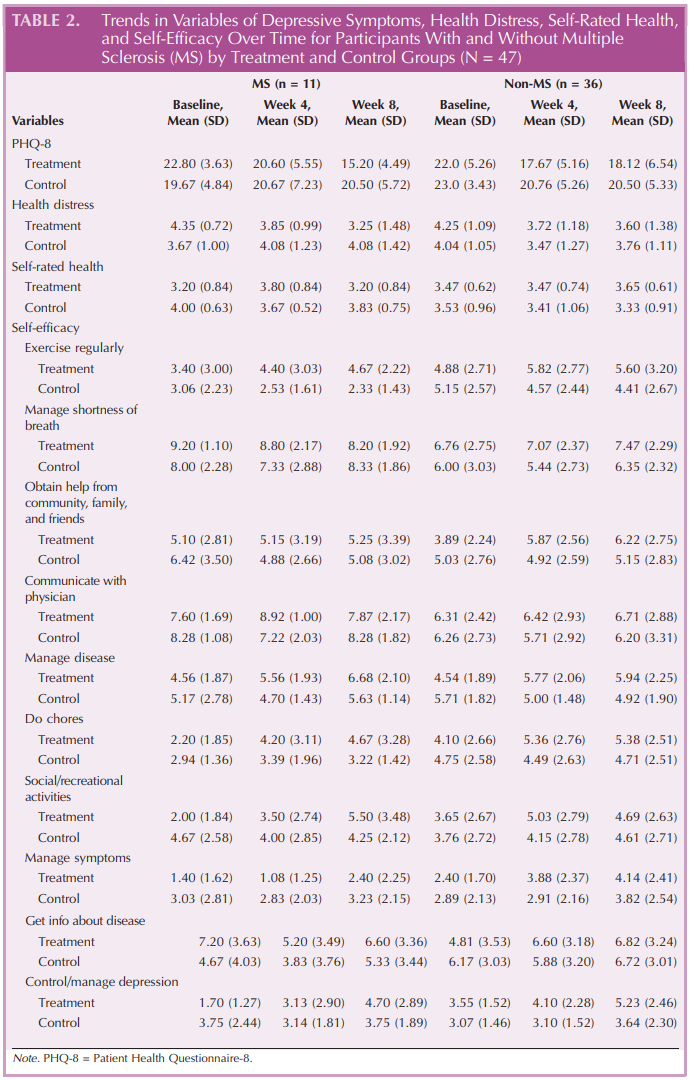

Mean PHQ-8 scores for MS versus non-MS participants in the treatment group at baseline were 22.80 versus 22.0 (for the control group, 19.67 vs 23.0), respectively, indicating severe depressive symptoms overall (Table 2). When investigating those with MS for clinically significant improvements on the PHQ-8, zero occurred in the control group (n = 6) versus 60% of the treatment group (n = 5), with an absolute risk reduction of 60%. The NNT was 2 (95% confidence interval, 1.0-6.2), indicating that 1 in every 2 treatment group participants with MS found clinically significant reductions in depressive symptoms from the intervention. Results from the full parent sample study found the NNT was 3 for those participants with any chronic disease exposed to the treatment.16 The 5 participants with MS who were randomized into the treatment arm completed 100% of the assigned online program modules and completed postprogram satisfaction surveys. This is higher than the 68% of the entire parent study group who completed the complete online program.16 Looking at mean score trends between baseline and week 8, MS participants in the treatment group experienced greater improvements on the PHQ-8 and health distress scores compared with non-MS participants (Supplemental Digital Content 1, available at http://links.lww.com/JNN/A113).

Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy measures for MS and non-MS participants at baseline and weeks 4 and 8 are presented in Table 2 comparing the treatment group with the control group. The lowest self-efficacy scores for both groups were those related to managing disease symptoms. Looking at the mean score trends between baseline and week 8, greater improvements were observed on self-efficacy measures of exercising regularly, social/recreational activities, and controlling/ managing depression in the MS treatment group. NonMS participants in the treatment group were shown to have higher self-efficacy scores on measures of managing shortness of breath and getting information about disease, whereas MS participants in the treatment group experienced a decline in those measures (see Supplemental Digital Content 1, available at http:// links.lww.com/JNN/A113).

Discussion

Differences were revealed when comparing the MS cohort with people with other chronic diseases in areas of program completion and outcomes. All people with MS in the treatment arm completed 100% of the assigned program activities and showed a greater mean reduction in depressive symptom burden than did those without MS. The MS treatment group showed a decrease in PHQ-8 scores, whereas the MS control group experienced an increase in PHQ-8 scores. The NNT result suggests that approximately half of those with MS who participate can expect a clinically significant improvement. This may speak to the receptivity or efficacy of psychologically based treatments as a whole for the MS population or may speak specifically to this modality or content structure.

The American Psychiatric Association states that response to a newly initiated depression treatment should be assessed within 4 to 8 weeks.21 A moderate improvement should be expected within this time, and if this improvement is not present, then the treatment plan should be reevaluated and modified. Once depressive symptoms have abated, a person should stay with the same medication regimen for 4 to 9 months and CBT is recommended to prevent relapse. Although self-report limits the accuracy of the data, it is noteworthy that only 2 of the 11 participants reported doses of antidepressants that were maximized as compared with dosing standards for MDD.22 Two participants were not on an antidepressant, and 4 were on the minimum US Food and Drug Administration dose of their antidepressant. Although the study did not allow researchers to review medical records, the prescribing pattern described in conjunction with high PHQ-8 scores at the start of the study supports the concern that people with MS are receiving inadequate depression treatment.9,10

Participants with MS in the treatment group reported greater self-efficacy in exercising regularly, social/recreational activities, and controlling/managing depression at the end of 8 weeks. Non-MS participants reported greater self-efficacy in managing shortness of breath and getting information about disease, whereas MS participants did not. A possible explanation is that shortness of breath was not a problem for this MS population and perhaps the intervention did not address their specific information needs. Favorable results could be due to the fact that the online modules encourage exercise and socialization and were instrumental in prompting participants to engage in these positive behaviors. In turn, it is conceivable that such activities contributed to the overall reduction in depressive symptoms as measured by the PHQ-8, although this theory requires further testing in a larger sample.

In the current study, participants with MS show a higher rate of online program completion than the other online CBT study mentioned previously, in which there was a 50% CBT module completion rate (6/12).15 The intervention in that study showed similar outcome trends to this study, where CBT participants showed less depression and those who did not receive CBT showed slightly more depression. Cooper et al15 asked for feedback from participants specifically regarding the rating scales used, and the participants felt that the Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale would be most appropriate for measuring their concerns. The question of how best to measure depressive symptom and track improvements among people with MS remains unclear due to the overlap between MS and MDD symptoms, as mentioned previously.

Limitations and Future Study

The primary limitation of this study is that it is a post hoc analysis of a small group within a larger study. Trends in improvements were based on descriptive statistics and thereby should be interpreted with caution. A further limitation of the present analysis is that there was no follow-up measurement of treatment effect beyond the conclusion of the study. Conclusions about standards of depression treatment are limited by patient self-report, as discussed previously. The authors plan to use these pilot data to support an adequately scaled study of this CBT intervention in the MS population, allowing for greater statistical power and including a wide range of MS participants.

The program in its current form cannot address psychiatric medication management. An opportunity for future study could include an in-person group CBT version of this intervention that could include a psychiatric provider and close tracking of medication adjustments. This variation would also allow direct comparison of online versus in-person delivery of the same CBT content.

Implications for Practice

Depression, self-efficacy, and physical outcomes are all closely linked for people with MS. There are also access-to-care barriers, such as geography, physical disability, transportation, and availability of psychiatric and neurologic providers, that prevent opportunities to screen for depression and self-care. Then, even when depression is identified, it is often undertreated by neurologists. Lack of depression treatment can then impair DMT adherence, therefore putting a person with MS at risk for MS relapses, brain atrophy, and disability progression. The present intervention offers a possible solution to this cascade of interrelated issues and gives participants a decreased likelihood of negative physical and emotional outcomes.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates that, for our small subsample of people with MS, high levels of undertreated depressive symptoms exist. Participants were receptive to the online program and had reductions in symptom burden when they used it, as evidenced by our NNT analysis. The current intervention aligns with established literature in terms of program length, and study participants exceeded the average program completion rate. Future randomized controlled studies can compare online program efficacy against standard care and other viable depression treatment alternatives for people with MS. Clinicians should actively screen and refer people with MS to depression treatment options that can reduce suffering and improve quality of life.

References

1. Feinstein A. Multiple sclerosis and depression. Mult Scler J. 2011;17(11):1276Y1281. doi:10.1177/1352458511417835

2. Lobentanz IS, Asenbaum S, Vass K, et al. Factors influencing quality of life in multiple sclerosis patients: disability, depressive mood, fatigue and sleep quality. Acta Neurol Scand. 2004; 110(1):6Y13. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.2004.00257.x

3. Passamonti L, Cerasa A, Liguori M, et al. Neurobiological mechanisms underlying emotional processing in relapsingremitting multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2009;132(pt 12):3380Y3391. doi:10.1093/brain/awp095

4. Hind D, Cotter J, Thake A, et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy for the treatment of depression in people with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:5. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-14-5

5. Olfson M, Blanco C, Marcus SC. Treatment of adult depression in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(10): 1482Y1491. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5057

6. American Psychiatric Association, ed. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

7. Minden SL, Feinstein A, Kalb RC, et al. Evidence-based guideline: assessment and management of psychiatric disorders in individuals with MS: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2014;82(2):174Y181. doi:10.1212/ WNL.0000000000000013

8. Katon WJ. Epidemiology and treatment of depression in patients with chronic medical illness. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13(1):7Y23. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/ PMC3181964/.

9. Raissi A, Bulloch AG, Fiest KM, McDonald K, Jett2 N, Patten SB. Exploration of undertreatment and patterns of treatment of depression in multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2015;17(6):292Y300. doi:10.7224/1537-2073.2014-084

10. Mohr DC, Hart SL, Fonareva I, Tasch ES. Treatment of depression for patients with multiple sclerosis in neurology clinics. Mult Scler J. 2006;12(2):204Y208. doi:10. 1191/135248506ms1265oa

11. Tarrants M, Oleen-Burkey M, Castelli-Haley J, Lage MJ. The impact of comorbid depression on adherence to therapy for multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Int. 2011;2011:1Y10. doi:10. 1155/2011/271321

12. Bruce JM, Hancock LM, Arnett P, Lynch S. Treatment adherence in multiple sclerosis: association with emotional status, personality, and cognition. J Behav Med. 2010;33(3): 219Y227. doi:10.1007/s10865-010-9247-y

13. Ledley DR, Marx BP, Heimberg RG. Making CognitiveBehavioral Therapy Work: Clinical Process for New Practitioners. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2010.

14. Hofmann SG, Asnaani A, Vonk IJ, Sawyer AT, Fang A. The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: a review of metaanalyses. Cognit Ther Res. 2012;36(5):427Y440. doi:10.1007/ s10608-012-9476-1

15. Cooper CL, Hind D, Glenys D, Parry GD, et al. Computerised CBT for treatment of depression in people with MS. Trials. 2011;12(259):1Y14. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-12-259

16. Wilson M, Hewes C, Barbosa-Leiker C, et al. Engaging adults with chronic disease in online depressive symptom self-management [published online ahead of print January 1, 2017]. West J Nurs Res. doi:10.1177/0193945916689068

17. Goalistics. Think Clearly About Depression. https://depression. goalistics.com/. Published 2015. Accessed January 18, 2017.

18. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, LPwe B. The patient health questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(4):345Y359. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010. 03.006

19. Lorig K, Stewart A, Ritter P, Gonzalez V, Laurent D, Lynch J. Outcome Measures for Health Education and Other Health Care Interventions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1996.

20. Klinkman MS, Bauroth S, Fedewa S, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes of care management for chronically depressed primary care patients: a report from the depression in primary care project. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(5):387Y396. doi:10.1370/afm.1168

21. Gelenberg AJ, Freeman MP, Markowitz JC, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder third edition. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/ assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd. pdf. Accessed October 10, 2016.

22. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Antidepressant medications: U.S. Food and Drug Administrationapproved indications and dosages for use in adults. 2013. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare-Medicaid-Coordination/ Fraud-Prevention/Medicaid-Integrity-Education/PharmacyEducation-Materials/Downloads/ad-adult-dosingchart.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2016.